A Wholesome, Hallowed, Gracious Christmas

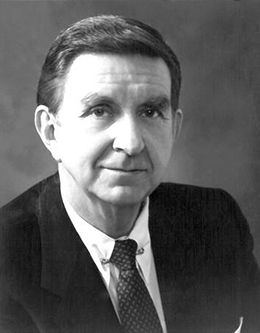

Assistant to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

December 11, 1973

Assistant to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

December 11, 1973

It’s an honor to be here. Although my present competence is geared more to a first-position version of “Flow Gently, Sweet Afton,” my years with the violin so long ago perhaps qualify me to express deep gratitude and some appreciation for that magnificent music. I am thankful.

It had occurred to me that I might talk today about a subject such as voluntary compliance with established standards, but I drove here on the freeway. I think I won’t discuss that subject today. Instead, I’d like to talk to you about the season. I am aware that examinations are dead ahead and would hope that in some marvelous way the alchemy of this special time of year might dissuade us temporarily from contemplating them and permit us to join together in consideration of this wonderful holy day season, which I love. I love its sights, its sounds, its scents, the thoughts and feelings that it inspires, its songs, its sentiments. I love the tenderness it evokes, the gratitude and generosity, the sensitivity to thanks and to giving, its acts of kindness and of love, the effect on family. I love what it does to release friendliness and goodwill between one man and another, which most of us keep under pretty rigid control the rest of the year. There are occasions, of course, when those carefully reserved feelings come forth naturally and spontaneously, as, for instance, when we’re caught under an awning in a downpour, or waiting behind a snowplow, or joined together in distress or action in the face of some calamity or personal difficulty. But of all these occasions, Christmas seems to be chief among those which bring out from good men, and maybe some of us less than good, those repressed emotions of brotherliness and kindliness.

I love the Christmas season. I love its spirit and its memories. It was at Christmas long ago that a tiny girl nestled snugly in my arms in the middle of the night and sighed with relief. She had been upchucking, perhaps from a slight overdose of excitement and anticipation, mixed with the season’s largess of goodies. “Daddy,” she said, “for a while I was afraid I was going to lose the Christmas spirit.”

And I love to remember the little hand on my knee as we rode through soft flakes of snow to our grandmother’s on Christmas morning. We had been singing with the carolers on the radio when she said, “What does it mean to adore him?”

I worked at an answer, but every attempt engendered more questions and further efforts to explain until finally, compassionately, she laid that little hand on my knee and said, “I guess to adore him just means to love him.”

Well, I come this morning with three themes, or one theme and two variations, to express briefly my love for the season. The theme is centered in a few words in a very familiar song, much like the one we sang together. These are the words. Have you heard them as well as sung them?

Joy to the world, the Lord is come.

Let earth receive her King.

Let every heart prepare him room,

And heaven and nature sing.

Seven hundred years before he came, Isaiah sang a sweet psalm of his coming:

The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light: they that dwell in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined. . . .

For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace. [Isaiah 9:2, 6]

His advent, of course, had been long anticipated. In God’s plan there was place and need for a sacrifice, an atoning sacrifice for sin. And so he came in due season, not as man anticipated but as God directed. There wasn’t any pomp; there were no blaring trumpets, no parade or ceremony, no army, no array of great ones ushering in the King. There was a crowded inn, a manger, a mother and a baby, some shepherds, and some wise men, unconscious of their different stations. There were angels and a message for those who had ears to hear.

They were all looking for a king

To set them free and lift them high;

Thou earnest, a little baby thing

To make a woman cry.

[Author unknown]

He grew, served, taught, learned obedience by the things which he suffered, and did, as he had been sent to do, the will of his Father.

When the appointed time came he was accused, mocked, arrayed in a purple robe. They platted a crown of thorns and put it about his head. They smote him with a reed and took him to be crucified. He was lifted up upon the cross by man that he might, as he said, “draw all men unto me, that as I have been lifted up by men even so should men be lifted up by the Father, to stand before me, to be judged of their works, whether they be good or whether they be evil” (3 Nephi 27:14).

On the cross he comforted those who suffered with him, he invoked the forgiveness of his Father for those who took his life, and in anguish he cried out to the God whose face for the moment may have been turned away from the awful scene—who knows, perhaps to wipe a tear. “Truly this was the Son of God,” said the centurion (Matthew 27:54). He rose, as we know, at the appointed time from the tomb in which he had been tenderly laid—the first that should rise. Resurrected, he companied for many days with his apostles and others, ascended to heaven as they watched him, visited his people in the American hemisphere and taught them, appeared to Paul and to Stephen, and in the last dispensation, with his Father, revealed himself to a boy prophet. As he promised, he will come again. For all of that I give thanks. I bear testimony that it is true. He will come again.

My first variation on the theme then, is thanksgiving, the second, and briefest part of this message. Christmas—and every other important holiday, it occurs to me—is a thanksgiving time: to mothers, to the founders of our country and the fathers of our free society, to those who have offered their lives to keep it free, to our loved ones departed, and at Christmas (always and every day, of course, but especially at Christmas) to God our Father and his holy Son, Jesus Christ. The past year has been full of perplexing problems; the possibilities ahead are certainly sobering in prospect. Yet the Christmas season brings to our hearts the spirit of thanks and of giving.

With Christ and gratitude and giving in our minds, then let me share with you the third part, or the second variation. It comes from another source, from another time. From Hamlet we read:

Some say that ever ’gainst that season comes

Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated,

This bird of dawning singeth all night long;

And then, they say, no spirit dare stir abroad,

The nights are wholesome, then no planets strike,

No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,

So hallowed and so gracious is that time.

[Hamlet, 1.i.158–64]

Wholesome, hallowed, gracious—what wonderful words. I love them. They represent to me all that Christmas and the season may mean. Think of them with me for a moment.

How to make the season wholesome? Why, by glancing healthfully inward for a moment. By seeking to bring ourselves more nearly to that measure of wholeness, of integrity, of unity with loftiest desires, of congruence with richest spiritual feeling, of harmony with that person that I would fondly like to be.

Many years ago a great man who taught at this university gave us a vision of the importance of that harmony. When I graduated from high school I wanted to come to Brigham Young University, with his name and face and strengths in mind. I really had in mind Harrison R. Merrill and BYU, in that order. If you know it well, rejoice with me; if not, be introduced to one of his greatest poems. He called it “Christmas Eve on the Desert.”

Tonight, not one alone am I, but three—

The Lad I was, the Man I am, and he

Who looks adown the coming future years

And wonders at my sloth. His hopes and fears

Should goad me to the manly game

Of adding to the honor of my name.

I’m Fate to him—that chap that’s I, grown old.

No matter how much stocks and land and gold

I save for him, he can’t buy back a single day

On which I built a pattern for his way.

I, in turn, am product of that Boy

Who rarely thought of After Selves. His joy

Was in the present. He might have saved me woe

Had he but thought. The ways that I must go

Are his. He marked them all for me.

And I must follow—and so must he—

My Future Self—Unless I save him!

Save?—Somehow that word,

Deep down, a precious thought has stirred

Savior?—Yes, I’m savior to that “Me.”

That thoughtful After Person whom I see!—

The thought is staggering! I sit and gaze

At my two Other Selves, joint keepers of my days!

Master of Christmas, You dared to bleed and die

That others might find life. How much more I

Should willingly give up my present days

To lofty deeds; seek out the ways

To build a splendid life. I should not fail

To set my feet upon the star-bound trail

For him—that After Self. You said that he

Who’d lose his life should find it, and I know

You found a larger life, still live and grow.

Your doctrine was, so I’ve been told, serve man.

I wonder if I’m doing all I can

To serve? Will serving help that Older Me

To be the man he’d fondly like to be?

Last night I passed a shack

Where hunger lurked. I must go back

And take a lamb, Is that the message of the Star

Whose rays, please God, can shine this far?

Tonight, not one alone am I, but three—

The Lad I was, the Man I am, and he

Who is my Future Self—nay, more:

I am His savior—that thought makes me four!

Master of Christmas, that Star of Thine shines clear—

Bless Thou the four of me—out here!

Wholesome, hallowed, gracious.

The angelic message was “Peace on earth, goodwill to men.” We do not despair of peace; yet we know something of history and something of the scriptures and something of present complexities, and we know that no one of us nor all of us here together can govern the world of men and their decisions. There is something we can do about peace in our lives and peace between us and our families and our neighbors—something—but we cannot control an insatiable world and the decisions of many men. But goodwill to men, what of that? Many of you are already experts in that adventure, but perhaps others have yet to learn that goodwill, like love, is more than language.

Do you know the words of Millay?

Love is not all; it is not meat nor drink,

Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain;

Nor yet a floating spar to men who sink.

[Edna St. Vincent Millay]

God so loved that he gave. Christ so loved that he gave. What of us? I remember the impressive words of Bonhoeffer, who said of Jesus that he was a man for others; and the words of Luther, who in his great speech on good works talked of Mary, who, having heard the announcement, went about her life preparing, not retired from the active scene because she had such knowledge, but involved in giving and growing and preparing.

For graciousness, how do you like the marvelous, simple story of the little boy who saw the bright, new automobile and said to its owner, walking about it on Christmas Eve:

“Is that your car, Mister?”

The man nodded. “My brother gave it to me for Christmas.”

The boy looked astounded. “You mean your brother gave it to you and it didn’t cost you nothing? Gosh, I wish—” He hesitated, and the man knew what he was going to wish. He was going to wish that he had a brother like that. But what the lad said jarred him all the way down to his heels. “I wish,” the boy went on, “that I could be a brother like that.”

Paul looked at the boy in astonishment. Then impulsively he said, “Would you like a ride in my automobile?”

“Yes,” said the little boy.

After a short ride, the youngster, his eyes aglow, said, “Mister, would you mind driving in front of my house?” Paul smiled a little. He thought he knew what the lad wanted. He wanted to show his neighbors that he could ride home in a big automobile. But he was wrong again. “Will you stop by those two steps?” the boy asked. He ran up the steps. In a little while Paul heard him coming back, but he was not coming fast. He was carrying his little polio-crippled brother. He sat him down on the bottom step, sort of squeezed up against him and pointed to the car. “There she is, Buddy, just like I told you upstairs. His brother give it to him for Christmas and it didn’t cost him a cent. And some day I’m going to give you one just like it. Then you can see for yourself all the pretty things in the Christmas windows that I’ve been trying to tell you about.”

Paul got out and lifted the little lad to the front seat of his car. The shiny-eyed older brother climbed in beside him, and the three of them began a memorable holiday ride.

That Christmas Eve Paul learned what Jesus meant about brotherliness and giving. [C. Roy Angell, in Guideposts]

And if I may add it, I’d like to tell you another thing I love very much about Christmas. I love to remember what the scripture says, and perhaps you are well aware of it: “Let brotherly love continue. Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares” (Hebrews 13:1–2).

There was a night when we had the blessing of having in our home a stranger, sorely afflicted. After all these years I have some hesitance to mention the incident, lest anyone know or connect her with it. She was from far away. She was away from her family. She had been incarcerated in institutions, had been released to go to her parents in another state, also far away, but after months of little progression and apparently with little hope in sight, had been relieved of her restraints there. Having affiliation with the Church, she found her way to Salt Lake City, to Temple Square, which she thought to be the heart of the Church, and sat across the desk from me, hopeless, her eyes blank, talking about her children, talking intermittently also about the voices she heard. She was ill. There was no appropriate place to send her, so we took her home.

Our holiday season was impaired a bit, as I now impair the memory by the repetition. That didn’t matter much. We missed a few parties; we felt someone should be with her, because she was obviously seriously ill. We didn’t know the therapy; we knew how to pray to God, and she joined us with our then very little family. The days went by. Christmas arrived. That morning she arose with us. She sat in a chair and watched as the presents were given and received. For everyone received by anyone else, she also received a gift. I fancied I saw the curtain going up a little. I watched a tear come trickling, and then, without premeditation and certainly without instruction, a little girl climbed onto her knee, put her arms around her neck, and said, “Susannah, I love you.” And the tears gushed and the curtain rose and the humanity came through. She wept, then talked freely about her little ones, about her husband at home, about her problems.

A little later I made a telephone call. I spoke to a man who was agonizing through the day. He didn’t want her away, but her illness had made it improbable to have her home. I talked with him of her present circumstance. He said, “Is there any way to get her home?” We found a way. There was an airplane and gracious people who made way, and a lady who got nervously aboard and soon thereafter arrived home to the arms of her own loved ones. She wrote us regularly for many years to thank us for a simple gift of brotherliness at a special time.

Oh, I love the words wholesome, hallowed, gracious. Among the many wonderful things I would like to remind you about, I love and will conclude with a brief statement from a great book written long ago. It is about a slave who lived in Christ’s time and watched him on a certain special Sunday in the midst of a multitude.

Suddenly, for no reason at all that Demetrius could observe, there was a wave of excitement. It swept down over the sluggish swollen stream of zealots like a sharp breeze. Men all about him were breaking loose from their families, tossing their packs into the arms of their overburdened children, and racing forward toward some urgent attraction. Far up ahead the shouts were increasing in volume, spontaneously organizing into a concerted reiterated cry; a single, magic word that drove the multitude into a frenzy.

“Do you know what is going on?” said Demetrius. [He was talking to another slave.]

“They’re yelling something about a king. That’s all I can make of it.”

“You think they’ve got somebody up front who wants to be their king? Is that it?”

“Looks like it. They keep howling another word that I don’t know—Messiah. The man’s name, maybe.”

Standing on tiptoe for an instant in the swaying crowd, Demetrius caught a fleeting glimpse of the obvious center of interest, a brown-haired, bareheaded, well-favored Jew. A tight little circle had been left open for the slow advance of the shaggy white donkey on which he rode. . . . There had been no effort to bedeck the pretender with any royal regalia. He was clad in a simple brown mantle with no decorations of any kind, and the handful of men—his intimate friends, no doubt—who tried to shield him from the pressure of the throng, wore the commonest sort of country garb.

It was quite clear now to Demetrius that the incident was accidental. . . . Whoever had started this wild pandemonium, it was apparent that it lacked the hero’s approbation.

The face of the enigmatic Jew seemed weighted with an almost insupportable burden of anxiety. The eyes, narrowed as if in resigned acceptance of some inevitable catastrophe, stared straight ahead toward Jerusalem.

Gradually the brooding eyes moved over the crowd until they came to rest on the strained, bewildered face of Demetrius. Perhaps, he wondered, the man’s gaze halted there because he alone—in all this welter of hysteria—refrained from shouting. His silence singled him out. The eyes calmly appraised Demetrius. They neither widened nor smiled; but, in some indefinable manner, they held Demetrius in a grip so firm it was almost a physical compulsion. The message they communicated was something other than sympathy, something more vital than friendly concern; a sort of stabilizing power that swept away all such negations as slavery, poverty, or any other afflicting circumstance. Demetrius was suffused with the glow of this curious kinship. Blind with sudden tears, he elbowed through the throng and reached the roadside. The uncouth Athenian, bursting with curiosity, inopportunely accosted him.

“See him—close up?” he asked.

Demetrius nodded.

“Crazy?” persisted the Athenian.

“No.”

“King?”

“No,” muttered Demetrius, soberly—“not a king.”

“What is he, then?” demanded the Athenian.

“I don’t know,” mumbled Demetrius, in a puzzled voice, “but—he is something more important than a king.” [Lloyd C. Douglas, The Robe, chapter 4]

I wish you a happy Christmas.

Joy to the world, the Lord is come.

Let earth receive her King.

Let every heart prepare him room,

And heaven and nature sing.

God bless us all that we, may have a wholesome, hallowed, gracious, special time. I bear witness that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, that he lives, that he governs, that he inspires and directs, that he will come again. God help us to worship in all the wonderful ways there are this season. In the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Marion D. Hanks was an Assistant to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 11 December 1973.