He could give that gift because of another one given long ago. God, the Father, gave his Son, and Jesus Christ gave us the Atonement, the greatest of all gifts and all giving.

Thank you, President Holland. I am delighted to be here with you. I pray that I may have the blessings of the Spirit so that I can say something useful to you.

A father asked me yesterday to advise him about giving a Christmas gift to his daughter. He just can’t decide whether or not to give this gift, or how to give it. His daughter is a college student; she may even be listening today. Her hectic life of school activities is made even harder because she doesn’t have a car. She begs rides, and she sometimes misses appointments. Her dad doesn’t have enough money for another car, at least not without some real sacrifice by his family. But he’s found a used car he might buy for her if he cuts enough corners on the family budget. And now he’s wondering. He asked me, “Will that car really be good for her, or will it be a problem? I love her, and she really could use it, but do you think it will help her or spoil her?” Let me guess. I can hear you rooting for the car: “Go for it! Go for it!”

I didn’t try to answer his question then, but I could sense his worry and sympathize with him. You ought to have sympathy for both givers and getters at Christmastime. Last night my sons, Matthew and John, and I spent time at a toy store. Above us a red Santa Claus spun slowly as the sound of a mother whispering with clenched teeth floated over the stacks of toys to our aisle: “Don’t tell me what your brother did to you. I saw everything. Do you want me to hit you right here in the store? Now you go outside and sit on that bench. And you stay there. And if you don’t I won’t get you a thing.” John and I shrugged and smiled at each other as we moved on, and I hummed inwardly, “Tis the season to be jolly. . . .”

Gift giving isn’t easy. It’s hard to give a gift with confidence. There are so many things that can go wrong. You wonder if the person on the other end will want it. My batting average on that is low. At least I think it is. You can’t really tell what gets returned after Christmas, but I am cautious enough that I always wrap the gift in the box from the store where I bought it.

I’ve always daydreamed of being a great gift giver. I picture people opening my gifts and showing with tears of joy and a smile that the giving, not just the gift, has touched their hearts. You must have that daydream, too. Many of you are probably already experts in gift giving. But even the experts may share some of my curiosity about what makes a gift great. I’ve been surrounded by expert gift givers all my life. None of them has ever told me how to do it, but I’ve been watching and I’ve been building a theory. I think it’s finally ready to be shared, at least among friends at this university. Here it is: The Eyring Theory of Gift Giving and Receiving. I call it a theory because it is surely incomplete. And calling it a theory means I expect you will change and improve it. I hope so, because then it will be yours. But at least I can help your theory building along.

My theory comes from thinking about many gifts and many holidays, but one day and one gift can illustrate it. The day was not Christmas nor even close to it. It was a summer day. My mother had died in the early afternoon. My father, my brother, and I had been at the hospital. As we walked out, my brother and I went to the car together, smiled, and looked up at the mountains. We remembered how Mother had always said she loved the mountains so much. He and I laughed and guessed that if the celestial worlds are really flat, like a sea of glass, she would be eager to get away to build her own worlds, and the first thing she’d build would be mountains. With that we smiled and got into the car and drove home. We went to the family home, and Dad met us there. There were just the three of us.

Friends and family came and went. In a lull, we fixed ourselves a snack. Then we visited with more callers. It grew late and dusk fell; I remember we still had not turned on the lights.

Then Dad answered the doorbell again. It was Aunt Catherine and Uncle Bill. When they’d walked just a few feet past the vestibule, Uncle Bill extended his hand, and I could see that he was holding a bottle of cherries. I can still see the deep red, almost purple, cherries and the shining gold cap on the mason jar. He said, “You might enjoy these. You probably haven’t had dessert.”

We hadn’t. The three of us sat around the kitchen table and put some cherries in bowls and ate them as Uncle Bill and Aunt Catherine cleared some dishes. Uncle Bill then asked, “Are there people you haven’t had time to call? Just give me some names, and I’ll do it.” We mentioned a few relatives who would want to know of Mother’s death. And then Aunt Catherine and Uncle Bill were gone. They could not have been with us more than twenty minutes.

Now, you can understand my theory best if you focus on one gift: the bottle of cherries. And let me explain this theory from the point of view of one person who received the gift: me. As we’ll see, that is crucial. What matters in what the giver does is what the receiver feels. You may not believe that yet, but trust me for the moment. So let’s start from inside me and with the gift of the bottle of cherries.

As near as I can tell, the giving and receiving of a great gift always has three parts. Here they are, illustrated by that gift on a summer evening.

First, I knew that Uncle Bill and Aunt Catherine had felt what I was feeling and had been touched. I’m not over the thrill of that yet. They must have felt we’d be too tired to fix much food. They must have felt that a bowl of home-canned cherries would make us, for a moment, feel like a family again. And not only did they feel what I felt, they were touched by it. Just knowing that someone had understood meant far more to me than the cherries themselves. I can’t remember the taste of the cherries, but I remember that someone knew my heart and cared.

Second, I felt the gift was free. I knew Uncle Bill and Aunt Catherine had chosen freely to bring a gift. I knew they weren’t doing so to compel a response from us. The gift seemed, at least to me, to provide them with joy just by their giving it.

And third, there was sacrifice. Now you might say, “Wait. How could they give for the joy of it and yet make a sacrifice?” Well, I could see the sacrifice because the cherries were home bottled. That meant Aunt Catherine had prepared them for her family. They must have liked cherries. But she took that possible pleasure from them and gave it to us. That’s sacrifice. However, I have realized since then this marvelous fact: It must have seemed to Uncle Bill and Aunt Catherine that they would have more pleasure if we had the cherries than if they did. There was sacrifice, but they made it for a greater return: our happiness. Most people feel deprived as they sacrifice to give another person a gift, and then they let that person know it. But only expert givers let the receiver sense that their sacrifice brings them joy.

Well, there it is—a simple theory. When you’re on the receiving end, you will discover three things in great gift givers: (1) they felt what you felt and were touched, (2) they gave freely, and (3) they counted sacrifice a bargain.

Now you can see it won’t be easy to use this theory to make big strides in your gift giving this Christmas. I don’t expect you’ll all rush out now and buy gifts brilliantly. It will take some practice—more than one holiday—to learn how to feel and be touched by what is inside someone else. And giving freely and counting sacrifice as joy will take a while. But you could start this Christmas being a good receiver. You might notice and you might appreciate. My theory suggests that you have the power to make others great gift givers by what you notice. You could make any gift better by what you choose to see, and you could, by failing to notice, make any gift a failure.

You can guess the advice I might have given my friend—the one with the careless daughter. Would a car be a good gift? Of course it could be, but something very special must happen in the eyes of that daughter. On Christmas morning, her eyes would need to see past the car to Dad and to the family. If she saw that he had read her heart and really cared, if she saw that she’d not wheedled the car from the family nor that they had given it to extract some performance, and if she really saw the sacrifice and the joy with which it was made for her, then the gift would be more than wheels. In fact, the gift would still be carrying her long after the wheels no longer turned. (And from the dad’s description of the car’s age, that time could come fairly soon.) Her appreciation, if it lasts, will make a great gift of whatever awaits her on Christmas morning.

Gift giving requires a sensitive giver and receiver. I hope we will use this little theory not to criticize the gifts that come our way this year, but to see how often our hearts are understood and gifts are given joyfully, even with sacrifice.

There is something you could do this Christmas to start becoming a better gift giver yourself. In fact, as students, you have some special chances. You could begin to put some gifts—great gifts—on layaway for future Christmases. Let me tell you about them.

You could start back in your room today. Is there an unfinished paper somewhere in the stacks? (I assume there are stacks there; I think I know your room.) Perhaps it is typed and apparently ready to turn in. Why bother more with it? I learned why during a religion class I taught once at Ricks College. I was teaching from section 25 of the Doctrine and Covenants. In that section Emma Smith is told that she should give her time to “writing and to learning much” (verse 8). About three rows back sat a blonde girl whose brow wrinkled as I urged the class to be diligent in developing writing skills. She raised her hand and said, “That doesn’t seem reasonable to me. All I’ll ever write are letters to my children.” That brought laughter all around the class. I felt chagrined to have applied that scripture to her. Just looking at her I could imagine a full quiver of children around her, and I could even see the letters she’d write in purple ink, with handwriting slanting backwards; neat, round loops; and circles for the tops of the i’s. Maybe writing powerfully wouldn’t matter to her.

Then a young man stood up, near the back. He’d said little during the term; I’m not sure he’d ever spoken before. He was older than the other students, and he was shy. He asked if he could speak. He told in a quiet voice of having been a soldier in Vietnam. One day, in what he thought would be a lull, he had left his rifle and walked across his fortified compound to mail call. Just as he got a letter in his hand, he heard a bugle blowing and shouts and mortar and rifle fire coming ahead of the swarming enemy. He fought his way back to his rifle, using his hands as weapons. With the men who survived, he drove the enemy out. The wounded were evacuated. Then he sat down among the living, and some of the dead, and he opened his letter. It was from his mother. She wrote that she’d had a spiritual experience that assured her that he would live to come home if he were righteous. In my class, the boy said quietly, “That letter was scripture to me. I kept it.” And he sat down.

You may have a child someday, perhaps a son. Can you see his face? Can you see him somewhere, sometime, in mortal danger? Can you feel the fear in his heart? Does it touch you? Would you like to give freely? What sacrifice will it take to write the letter your heart will want to send? You won’t do it in the hour before the postman comes. Nor will it be possible in a day or even in a week. It may take years. Start the practice this afternoon. Go back to your room and write and read and rewrite that paper again and again. It won’t seem like sacrifice if you picture that boy, feel his heart, and think of the letters he’ll need someday.

Now, some of you may not have a paper waiting for you. It may be a textbook with a math problem hidden in it. (They hide them these days; the math is often tucked away in a special section that you can skip. And so many of you do.) Let me tell you about a Christmas in your future. You’ll have a teenage son or daughter who’ll say, “I hate school.” After some careful listening, you’ll find it is not school or even mathematics he or she hates—it’s the feeling of failure.

You’ll correctly discern those feelings and you’ll be touched; you’ll want to freely give. So you’ll open the text and say, “Let’s look at one of the problems together.” Think of the shock you will feel when you see that the same rowboat is still going downstream in two hours and back in five hours, and the questions are still how fast the current is and how far the boat traveled. Just think what a shock it will be when you remember you’ve seen that problem before. Why, that rowboat has been in the water for generations! You might think, “Well, I’ll make my children feel better by showing them that I can’t do math either.” Let me give you some advice: They will see that as a poor gift.

There is a better gift, but it will take effort now. My dad, when he was a boy, must have tackled the rowboat problem and lots of others. That was part of the equipment he needed to become a scientist who would make a difference to chemistry. But he also made a difference to me. Our family room didn’t look as elegant as some. It had one kind of furniture—chairs—and one wall decoration—a green chalkboard. I came to the age your boy or girl will reach. I didn’t wonder if I could work the math problems; I’d proved to my satisfaction that I couldn’t. And some of my teachers were satisfied that that was true, too.

But Dad wasn’t satisfied. He thought I could do it. So we took turns at that chalkboard. I can’t remember the gifts my dad wrapped and helped put under a tree. But I remember the chalkboard and his quiet voice. In fact, there were some times when his voice was not quiet at all—he did shout, I’ll have to admit in his presence—but he built up my mathematics, and he built up me. To do this took more than knowing what I needed and caring. It took more than being willing to give his time then, precious as it was. It took time he had spent earlier when he had the chances you have now. Because he had spent time then, he and I could have that time at the chalkboard and he could help me. And because he gave me that, I’ve got a boy who has let me sit down with him this year. We’ve rowed that same boat up and down. And his teacher wrote “much improved” on his report card. But I’ll tell you what’s improved most: the feelings of a fine boy about himself. Nothing I will put under the tree for Stuart this year has half the chance of becoming a family heirloom that his pride of accomplishment does.

Now I see some art (or are they music?) majors smiling. They’re thinking, “He surely can’t convince me there’s a gift hidden in my unfinished assignments.” Let me try. Last week I went to an Eagle Scout court of honor. I’ve been to dozens, but this one had something I won’t forget. Before the Eagle badge was given, there was a slide and sound show. The lights went down, and I recognized two voices on the tape. One was a famous singer in the background, and the other, the narrator, was the father of the new Eagle Scout. The slides were of eagles soaring and of mountains and of moon landings. I don’t know if the Eagle Scout had a lump in his throat quite the size of mine, but I know he’ll remember the gift. His dad must have spent hours preparing slides, writing words that soared, and then somehow getting music and words coordinated for the right volume and timing. You’ll have a boy someday who will be honored at such an event, with all his cousins and aunts and uncles looking on. And with your whole heart, you’ll want to tell him what he is and what he can be. Whether you can give that gift then depends on whether you feel his heart now and are touched and start building the creative skills you’ll need. And it will mean more than you now can dream, I promise you.

There is yet another gift some of you may want to give that takes starting early. I saw it started once when I was a bishop. A student sat across my desk from me. He talked about mistakes he had made. And he talked about how much he wanted the children he might have someday to have a dad who could use his priesthood and to whom they could be sealed forever. He said he knew that the price and pain of repentance might be great. And then he said something I will not forget: “Bishop, I am coming back. I will do whatever it takes. I am coming back.” He felt sorrow. And he had faith in Christ. And still it took months of painful effort. Finally, he asked if it were enough. And he said he didn’t want me to guess; he wanted to be sure.

About that time a kind priesthood leader took me aside and asked me if I had any questions. I said that I did, and I asked how I could know when a person has done what it takes to be forgiven. To my surprise, he didn’t give me a lecture on repentance or on revelation. He just asked some questions. They weren’t what I had expected. They were questions like these: “Does he attend all his meetings?”

“Yes.”

“Does he come on time?”

“Yes.”

“Does he do what he is asked?”

“Yes.”

“Does he do it promptly?”

“Yes.”

The questions went on that way for a few minutes. And all the answers were the same. Then he said “Do you have your answer?”

And I said, “Yes.”

And so somewhere this Christmas there is a family with a righteous priesthood bearer at its head. They have eternal hopes and peace on earth. He’ll probably give his family all sorts of gifts wrapped brightly, but nothing will matter quite so much as the one he started a long time ago in my office and has never stopped giving. He felt then the needs of children he’d only dreamed of, and he gave early and freely. He sacrificed his pride and sloth and numbed feelings. I am sure it doesn’t seem like sacrifice now.

He could give that gift because of another one given long ago. God, the Father, gave his Son, and Jesus Christ gave us the Atonement, the greatest of all gifts and all giving. They somehow felt all the pain and sorrow of sin that would fall on all of us and everyone else who would ever live. I testify that what Paul said is true:

We have a great high priest, that is passed into the heavens, Jesus the Son of God.

For we have not an high priest which cannot be touched with the feeling of our infirmities; but was in all points tempted like as we are, yet without sin.

Let us therefore come boldly unto the throne of grace, that we may obtain mercy, and find grace to help in time of need. [Hebrews 4:14–16]

I bear you my testimony that Jesus gave the gift freely, willingly, to us all. He said, “Therefore doth my Father love me, because I lay down my life, that I might take it again. No man taketh it from me, but I lay it down of myself” (John 10:17–18). All men and women come into this life with that gift. They will live again, and if they will, they may live with him.

And I bear you testimony that as you accept that gift, given through infinite sacrifice, it brings joy to the giver. Jesus taught, “I say unto you, that likewise joy shall be in heaven over one sinner that repenteth, more than over ninety and nine just persons, which need no repentance” (Luke 15:7).

If that warms you as it does me, you may well want to give a gift to the Savior. Others did at his birth. Knowing what we do, how much more do we want to give him something. But he seems to have everything. Well, not quite. He doesn’t have you with him again forever, not yet. I hope you are touched by the feelings of his heart enough to sense how much he wants to know you are coming home to him. You can’t give that gift to him in one day, or one Christmas, but you could show him today that you are on the way. You could pray. You could read a page of scripture. You could keep a commandment.

If you have already done these things, there is still something left to give. All around you are people he loves and can only help through you and me. One of the sure signs that a person has accepted the gift of the Savior’s Atonement is gift giving. The process of cleansing seems to make us more sensitive, more gracious, more pleased to share what means so much to us. I suppose that’s why the Savior spoke of giving in describing who would finally come home.

Then shall the King say unto them on his right hand, Come, ye blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world:

For I was an hungered, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in:

Naked, and ye clothed me: I was sick, and ye visited me: I was in prison, and ye came unto me.

Then shall the righteous answer him, saying, Lord, when saw we thee an hungered, and fed thee? or thirsty, and gave thee drink?

When saw we thee a stranger, and took thee in? or naked, and clothed thee?

Or when saw we thee sick, or in prison, and came unto thee?

And the King shall answer and say unto them, Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me. [Matthew 25:34–40]

And that, I suppose, is the nicest effect of receiving great gifts. It makes us want to give, and give well. I’ve been blessed all my life by such gifts. I acknowledge that. I’m sure you do, too. Many of those gifts were given long ago. We’re near the birthday of the Prophet Joseph Smith. He gave his great talent, and his life, that the gospel of Jesus Christ might be restored for me and for you. Ancestors of mine from Switzerland and Germany and Yorkshire and Wales left home and familiar ways to embrace the restored gospel, as much for me as for them, perhaps more. It was ten years after the Saints came into these mountains before my great-grandfather’s journal shows one reference to so much as a Christmas meal. One entry reads, in its entirety: “December 25, 1855: Fixed a shed and went to the cedars. Four sheep died last night. Froze.” I acknowledge such gifts, which I only hope I am capable of sending along to people I have not yet seen.

And so shall we do what we can to appreciate and to give a merry Christmas?

“Freely ye have received, freely give” (Matthew 10:8). I pray that we will freely give. I pray that we will be touched by the feelings of others, that we will give without feelings of compulsion or expectation of gain, and that we will know that sacrifice is made sweet to us when we treasure the joy it brings to another heart. For this I pray, in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

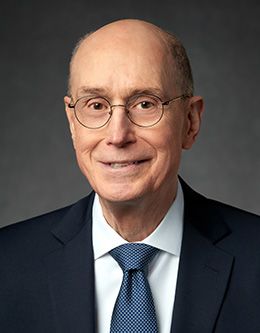

Henry B. Eyring was Commissioner of the Church Educational System of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 16 December 1980.