While five or six years of graduate school may have started us on the path toward becoming pretty good scientists or literary scholars, they did not necessarily qualify us to redesign the campus, or to replace Norm Chow in calling the football plays, or to run the Church.

At the beginning of my remarks I also wish to take the privilege of again extending my thanks to Stan Albrecht and Dennis Thomson. I recently reread the talk that Stan gave to us on this occasion last year, and I was struck once more with his insight and devotion. Stan gave as much of his energy to this institution as anyone could, and my admiration for him is deep and strong. I miss him very much in our office. President Holland once said of Dennis that “he wears well.” This is a perceptive comment, because Dennis does work that is thorough and thoughtful. His influence will be lasting in the university, and I miss him as well.

I am also very grateful that Clayne Pope and John Tanner have agreed to join with Bevan Ott and Bob Webb in the academic vice president’s office. I have already come to rely heavily on all of these fine colleagues.

As I begin my term in this present office, I would like to provide an evaluation of a number of aspects of BYU and then list several wishes I have for the university in the future. Although I am dependent on many colleagues for both data and perspectives, my observations will necessarily be personal. For those whose experience with the university predates mine, I apologize for the beginning point. But reflecting on what I have observed helps me to note the immense development of this institution over the years. It also helps me to remain convinced that the direction we have received from our board has consistently aimed us toward the kind of university we should be striving to become.

My first memory of Brigham Young University is only fleeting and impossible for me to date precisely, but it must have occurred sometime in late 1940 or early 1941. My dad, who joined the faculty here in 1938, brought me up the south entry of the campus and, among other things, showed me the workers who must have been just finishing the Joseph Smith Memorial Building. With the Smith Building completed, even more of the activities of the college students moved to upper campus, as we called it. There were, after all, four major academic buildings up here, so more room could be made down below for the training school and BY High, which shared the lower campus with the college. Those who were around when the next construction began undoubtedly knew that a few more buildings might sometime be built, but only the rare visionary, who remembered talk of temples of learning covering the entire hill, could possibly have anticipated the current campus with its hundreds of acres. While buildings do not make a university, I still think that the contrast of these two times on our campus presents a pretty good symbol of the distance we have come.

(I have another, still less academic example. My first chance to have any schooling through BYU came in 1946, when I transferred to the BY Training School in the fourth grade. At that time our activity cards got us into the home football games of the college. I was going to show you the football schedule from that year and compare it to this fall’s schedule, but that wouldn’t really be fair—football was barely back on campus after being furloughed during WW II. So I chose to make the comparison with 1949, the year I got to go over to the junior high school (Figure 1). You will note that while some of the opponents were universities we play today, several others have given up football. None of us in those days could have imagined that we would play UCLA, Penn State, and Notre Dame in one season.)

Throughout this talk, I will occasionally refer back to older times to help put today’s university into perspective, but I will concentrate largely on what I believe to be our strengths and some of our most important challenges. I will begin with our students.

There is no doubt in my mind that a combination of demographics in the Church, forward-thinking admissions policies, increased parental involvement, enlarged academic reputation, and low costs has brought us the brightest and best-prepared students in the university’s history. The rate of increased qualifications is clearly accelerating. Figure 2, for example, shows the average GPA and ACT scores of the entering classes for the past four years (Figure 2). When we get increases of as much as one-half GPA or one-half ACT point in a year, we are changing substantially. To put the ACT scores in perspective, note the chart showing the percentiles of the scaled scores (Figure 3). We are now taking almost our entire entering class from the highest quarter of those who are taking the examination. You will note that because of the nature of scaled scores, very little differentiation is made at the ends. Thus any student who receives a 31 or above falls into the highest one percentile in the nation. For the fall of 1992, we have accepted over 800 students who fall in this category. Some of them will go elsewhere, but a great majority of them will be in our classes next week.

There are other data about students that are instructive. The next chart shows the top 20 universities in the United States in terms of National Merit Scholars enrolled in 1991 (Figure 4). (The information for 1992 is not yet available, but we do not anticipate much of a change in our position.) You will note quite a drop from Harvard at the top, but our tie for tenth position puts us in the middle of some very impressive company.

As the word got out that our colleagues in admissions were moving from predicted college grades to a preparation index as the primary admissions criterion, our potential students began to enroll for better and better high school courses. One result of this development has been a spectacular boom in the number of students enrolled in advanced placement courses in the high schools from which we draw the majority of our students. The result of this dramatic increase is that we are among the top three universities in the United States when it comes to the number of applications for AP credit we receive (Figure 5). I am aware that there are reasons to be careful about how we use this credit, and we will continue to review both the test levels at which we grant credit and how we count it at BYU. But you will note again that the other universities in this list are some with which we would be pleased to be compared. And there is no doubt that the AP courses give our students excellent preparation for the classes they will take here.

I would like to also comment on the religious and spiritual capacities of our students. Here I will be cautious: I have written elsewhere that my roles as a judge caused me more apprehension than any other part of being a bishop, and I had been set apart to make judgments. I sincerely wish that we would all exercise restraint when we presume to evaluate the spiritual condition of others. But I think that we have very good young people who are admitted here. I cannot tell whether they are the best we have ever had, but it is my opinion that they are clearly further removed from the worldly culture from which they come than any previous group. That is, when you compare them to the others who were in their high schools, and when you see the bombardments from the media and environment to which they have been subjected, they are remarkably strong and good. I know of some of their problems, but when I visit the BYU married ward to which I am assigned as a high councilor, I am constantly reminded how much more seriously they study the gospel and how much more they trouble themselves over the welfare of others than my acquaintances and I did when we were their age.

Thus I am a little unhappy when an occasional colleague belittles our admissions process with such comments as “Now if you could only get us some spiritual students.” We know that some unworthy students do come to BYU, and we are trying to be as careful as possible to insure that bishops and others do not use us as a place to reform their wayward young people. We have made several significant changes to the admissions procedures in an attempt to make sure that we are as thorough as possible in this respect. But what troubles me in such comments in the implication that increasing the academic qualifications of the students automatically lowers their religious commitments. I believe that at their roots these remarks are insulting to the Church when they imply that the gospel is most appealing to the less intelligent or less well educated. I would never wish to imply the spiritual superiority of the bright and learned; the most faithful person I met on my mission was among the most humble in these respects. But the fact that we have a Church university should argue against the opposite perspective. I am very pleased with our students’ religious commitments in most important respects. Altogether they are the best we have ever had.

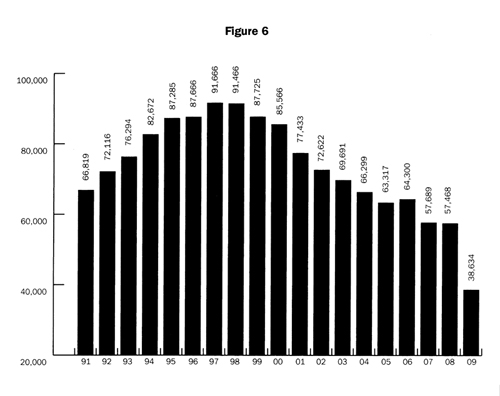

We do have a number of significant issues to face in relation to our students. The most troubling of these for me is the fact that we can admit only an increasingly small number of those who are qualified and worthy. In case you have not seen the actual figures, here are the data on the number of Church members in the United States and Canada who will turn 18 during the next period of time (Figure 6). You will note that we will have significant increases until the year 1997, when a decline should start. But we have difficulty knowing whether or to what degree that decline will happen, since these figures only include those young people who are on current Church records and do not account for any conversions, which we know will occur. Moreover, these figures say nothing about potential students from outside the U.S.-Canada area.

One immediate challenge we have faced as various factors have pushed up our test scores is that competition for our limited scholarship money has become more and more keen. Recently our scholarship office prepared us a report in which they showed that we would need more than a million additional dollars for this fall if we were to award freshman scholarships at the same qualification level we used in 1989. Students who are being offered four-year scholarships at other universities often have to settle for a one-year, one-half tuition scholarship here. Let me give you an example from this year’s scholarship procedures. As you know, up to a certain point we weight our scores to account for the percent of basic courses that students have taken in high school. Arbitrary numbers are assigned that combine GPA and ACT plus the percent of basics. For students whose high school enrollment included at least 70 percent of basics, the point at which we awarded a four-year scholarship was 2.83 on the preparation index. This means that a student would be awarded such a scholarship if she or he had a 31 on the ACT (remember, this is in the first percentile) and a 4.0 grade point average. The GPA can drop clear down to 3.9 if the student achieves a 32 on the ACT. Finding sufficient funding to keep this situation from getting even worse is a major challenge. But we should also remember that all students who enroll here receive the equivalent of a two-thirds scholarship through the Church’s investment in their education.

The increasing admissions levels also challenge us in our efforts to maintain a very desirable diversity in our student body. We have added a number of procedures in the admissions process (at a great time cost to the faculty and other members of the admissions committee, I would add) in an attempt to make sure that admission to BYU is not based solely on grades and test scores. But it would not be fair to the student who works diligently to qualify for admission if preparation were not a major factor. This preparation factor, however, cannot help but give an advantage to the young people whose families and friends begin early to guide them into the right classes and to stimulate them toward high academic achievement. Those young people without cultural support, and especially new converts from minority backgrounds, may not really be able to compete. We have begun to put in place a minority transfer consortium with a number of two-year feeder institutions, and we are aggressively recruiting qualified minority students. But we will continue to be challenged by the diversity problem. On the one hand, we cannot afford to bring in less-qualified students who will struggle unnecessarily in this challenging academic environment. On the other hand, we can ill afford to have our students become less and less representative of the young people in the Church.

Exacerbating our admissions problems is the matter that is generally called “throughput” in the literature of higher education. For a very complex number of reasons, students are taking longer and longer to graduate. This is not a problem limited to BYU. Indeed, some writers simply assert that the four-year college degree is a thing of the past. But many fine universities do a much better job getting students graduated than we do. Our students are averaging 11.9 semesters of enrollment before they graduate. Obviously, thousands of additional students could have an education here if we could improve our average even to 10 semesters. Now is not the time to discuss all of the actions that should be undertaken in this effort, but I would say that departments, colleges, and individual faculty will make most of the difference here.

As bright and prepared as they are, our students have some problems that we need to acknowledge. Few of them write well, and many will be hindered throughout their academic and professional careers if we do not continue and increase the very fine efforts of many of our units in insisting on a good deal of well-evaluated writing in classes across the university.

Unfortunately, many of these qualified and prepared students fail at their university experience. Last fall semester, 3,208 students were placed on academic warning or probation or were suspended from the university for academic reasons. Of these, between six and seven hundred were members of the freshman class, the most qualified class we have ever admitted. These figures mean that about one in 10 of the students enrolled last fall failed to achieve even minimal academic success. Clearly, there are many factors involved here, but we surely cannot expect that all student problems will be solved through higher admissions levels.

A walk around campus will soon convince all of us that a portion of our students still have not come to a conviction about the nature of honor. Like many of you, I am concerned that students will sign a pledge to observe the Honor Code and the Dress and Grooming Standards and then not do so. To me, honor is the most important part of the academic experience. I support completely the kinds of efforts to promote honor that were presented to us today. I think it is imperative that no student would ever be in doubt about a teacher’s determination to award credit only to those students whose actions demonstrate the highest levels of honor.

These last comments about some problems our students have, and some of the challenges that we are facing because of increased quality, should not detract from my most important point: Our students are among the finest young people in the world, and they continue to make this university better than ever before.

Before I discuss some aspects of faculty performance, I would like to make a few comments on the support that the university receives. Here again, I believe we have every reason to be grateful and optimistic.

An issue of the Chronicle of Higher Education published just a couple of weeks ago reported the results of a survey of over 500 colleges and universities in the United States. More than 81 percent of the institutions responded, and the results were very disturbing. Let me quote one short paragraph: “Nearly 60 percent of all colleges and universities experienced cuts in their operating budgets in 1991–92, forcing many to raise tuition, freeze faculty hiring, offer fewer sections of courses, or delay building repairs.” By the same percentages, colleges anticipate further cuts in their 1992–93 operating budgets. Those colleges and universities most hurt were state operated. Many of you have heard of the drastic cuts at most of the institutions in the California State University System, where one university is contemplating eliminating at least seven departments and cutting as many as 190 faculty positions, of which about half are tenure or tenure-track positions. Forty-two percent of all public four-year colleges reported that they would provide no salary increases for faculty members in 1992–93, and 48 percent of these same institutions had imposed a freeze on hiring. But state universities are not alone: financial problems are challenging some of the most prominent private universities. One very prestigious Ivy League college reports that it needs about one billion dollars to repair its crumbling infrastructure.

Our situation at BYU is vastly better than is found elsewhere. Because of the careful financial practices of our board of trustees, we have not been subjected to the financial swings of other institutions. We have not only had modest salary increases this year, but the board also authorized salary adjustments, some quite substantial, for those full professors whose disciplines were shown to have fallen behind our reference group. University administrators throughout the country would be shaking their heads in disbelief if they knew how the board had treated us in this extraordinarily challenging financial atmosphere.

And because of the wise program of continuing maintenance at BYU, we are not going to find ourselves with most of our buildings collapsing. We have replaced the Joseph Smith Building, and the new science building and the renovation of the Eyring Science Center have received initial approval. We are also in the planning stage for expanding our two major libraries.

This continuing financial support—even in the face of a slumping economy and severe economic challenges elsewhere in higher education—does not mean, of course, that we are without our own problems. We may be the most efficient university in the country when it comes to the use of physical facilities, but we are very pressed when it comes to office, laboratory, and classroom space. Any number of you have reminded me of your special needs since I took this office only a few weeks ago. I expect that we will always have both financial needs and wants.

One area in which we are particularly challenged is in our libraries. As you are aware, major libraries across the nation face impressive obstacles to their efforts to continue providing faculty and students with the resources necessary to engage in informed teaching, meaningful research, and other forms of scholarly dialogue and learning. Our libraries no longer can house our collections, and, as noted, we are in the planning stage for additions. But one of the most serious financial challenges we face will not disappear with new facilities. The escalating cost of serials poses particularly difficult decisions. Essential academic journals range from $20 to $8,000 annually, and some of them have increased in cost over 400 percent during the past five years. We will have no choice but to discontinue some subscriptions. Because this is such a critical faculty matter, the library staff and Faculty Library Council will involve departments and disciplines in trying to determine which periodicals are most valuable to us.

But even while we are facing these important decisions, the libraries are undertaking important initiatives to increase the usefulness of the present collection to undergraduates, graduate students, and faculty alike. The Faculty Library Council, your departmental library representatives, and the library staffs will be happy to show you these helpful innovations.

I do not expect to see the day when we will not be faced with difficult resource decisions and when our needs and desires do not outstrip our ability to pay for them. But again, I am struck by how well we are supported and how far we have come in the two and one-half decades I have been here.

My evaluation of the faculty is overwhelmingly optimistic. I wish that I could have thought of some dramatic way to symbolize your extraordinary work in a visual way. But stacks of graded examinations and papers, or of books and articles published, while dramatic, don’t convey much information. I do have some observations, however.

First, I believe that the faculty are overwhelmingly hard working. A recent thorough study (conducted by Bruce Chadwick, Howard Christensen, and David Magleby) of faculty time use shows that the average faculty member spends close to 50 hours per week in university business. Teaching takes about half of our time, and research and service take about one-quarter each. When each one adds family and Church activity to this list, it is clear that we are very busy.

The results of this hard work are easy to note. Our research productivity has increased at a rapid pace. A separate study by Bruce Higley indicates that the percentage of our time dedicated to teaching has remained remarkably steady since 1975. Yet we have hardly one department in which published results of our study have not doubled or tripled during that time. We need to be cautious in drawing conclusions, but a combination of various data would indicate that the vastly improved research productivity has not come at the expense of effort applied to teaching.

Because it is available through my own experience, I would like to give one example of the level of this scholarly productivity. Near the middle of my career here, the dean of the College of Humanities issued a 10-year bibliography of work published by that faculty. Last year the annual college bibliography contained more entries than were in the earlier 10-year collection.

Our goals in respect to this aspect of our assignments have been articulated very clearly in the memorandum to the faculty entitled “A Community of Scholars.” I commend it and its message to you and hope that those who have not yet chosen to expand their teaching to a broader community will consider its contents particularly carefully.

There are a few ways to compare the teaching of the present with that of the past. I have already mentioned that our teaching effort remains largely unchanged, and excellent training and active research clearly make our present faculty stronger than ever in mastery of the subject matter. Moreover I have seen no evidence that there is any diminution of our concern for our students. I have asked two colleagues to look at the size of our classes over time, and I suspect that they will discover that our average class size has increased. If so, we may have greater challenges than in the past when it comes to giving personal attention to our students. But my intuitive conclusion is that in general we have not only maintained BYU’s long tradition of excellent teaching, but we have also made progress in this matter.

I also believe that an overwhelming majority of our faculty are very supportive of our sponsoring Church. Again I hesitate to measure the strength of testimonies, but we do have data that indicate that faculty here are fulfilling a wide range of important Church callings. Moreover, my opportunity to observe faculty for most of five decades makes me pretty secure in the observation that our present faculty is as faithful as at any time in the past. I have no hesitation in recommending almost all of us as teachers and models for our children and those of other Church members.

There are a few habits of a minority of our faculty that I wish could be changed. For example, I am constantly amazed that some of the same faculty who ridicule conspiracy theories in the political world are certain that conspiracies run the university. As in politics, these theories often are used by both ends of the spectrum on any issue. I have heard the term “The Gang of 50,” which apparently refers to a group of faculty and administrators who are plotting to secularize the university by forcing up our expectations. But another group insists with equal fervor that those same faculty and administrators are really trying to reverse the progress that has been made in the past and stop any important academic undertakings.

The fact is that conspiracies are very difficult to maintain and thus very unlikely. But such talk can start to become a disservice when it distracts us from the real problems and issues in the university. We need to discuss difficult questions—including how best to distribute limited resources, how to fulfill our prophetic mission on a day-to-day basis, how to balance competing interests for faculty time, etc.—and such discussion becomes very difficult when even a few faculty feel that all decisions have already been made in some clandestine fashion. Moreover, conspiracy theories deprive us of one of the most frequent of human products: the mistake. The fact is, a lot of our problems don’t result from some sinister plot, but from the mere fact that we make mistakes—some of them dumb. As a dean and associate vice president (not to mention husband, father, and friend), I’ve made some pretty big mistakes, and I can almost guarantee you that this is one tradition I’ll continue. I’ve also avoided some equally big mistakes because someone counseled me about the course I had chosen. But those who feel that every administrative action is the result of some brilliant, undercover master plan will never believe enough in dumbness to give us help. All of us are the poorer when this happens.

Some other small groups seem to be far too enamored of their graduate school experience. Clearly, our contacts with world-famous professors in the great research universities should be viewed in a very positive light, and we can learn much from these institutions. But they are rarely very good models for BYU, and those who would try to remake us in the image of such universities often push us in directions that are not in our best interest. I believe that we need to spend more time discovering how to be the best BYU and less trying to be a poor imitation of something else.

I also wish that we would not overvalue the abilities that our experiences at these universities helped us sharpen. While five or six years of graduate school may have started us on the path toward becoming pretty good scientists or literary scholars, they did not necessarily qualify us to redesign the campus, or to replace Norm Chow in calling the football plays, or to run the Church. I recognize the temptation to tell Norm after the fact that a draw play couldn’t possibly have worked in those circumstances, and besides, trying to out-guess him is probably quite harmless (as long as neither he nor LaVell listens to us). The implications, however, about second-guessing prophets should be obvious.

To make my personal position on this last matter as unambiguous as possible, let me say the following: I believe that the leaders of this Church are prophets, that the President of the Church has the same authority from God and his son as did Moses or the other prophets of ancient times or this dispensation. Because of this belief, I wish to follow their direction in the same way that I hope I would have followed that of Moses. I hope that during a plague of snakes I would have fastened my eye on a serpent of brass rather than advising Moses that my training had taught me we should use snakebite kits. Moses accepted advice from Jethro and others when he felt it was right. But the record of those who rebelled against him was miserable.

Fortunately, as was the case when I acknowledged some problems with our students but recognized their great strengths, I can also certify that our faculty is of the highest quality. I can no longer separate the idea of being a professor from that of being a BYU professor. For me, association with you is one of the most important aspects of my life.

Clayne Pope has given me good counsel ever since I first met him. He recently cautioned me that our office should select a small number of issues to which to turn our main attention. He feels, rightly I’m sure, that long lists of goals dissipate energy and raise unfulfillable expectations. We are now in the process of selecting those issues where we can concentrate our attention.

But with your indulgence I am going to expand beyond that small list as I conclude this talk. I suppose what follows might be called my “wish list,” because it includes several items, some of which we in the administration can influence only minimally. In a few cases I’ll expand on the item. With others, I will simply list the challenge. The order is pretty well random, and I use numbers only to keep them separate.

1. I wish that we would take much better care of our students, particularly our freshman and those who are academically at risk or struggling. Because of our relations to them in the Church and the natural commitments of most of us as teachers, many of us individually do remarkable things for these young people. But we are far behind other institutions in establishing programs to mitigate the shock of the transition from high school to the university. And students who are not doing well need far more faculty and departmental attention.

2. I wish that we would think of effective ways to stress international matters at our institution. Certainly some of our richest intellectual resources are the foreign-language abilities and international experiences of our students. While some programs have moved to take advantage of this treasure, many have not. As Cheryl Brown has put it, we’ve been content to harvest the timber above a rich gold mine.

3. I wish that all of us, to the extent of our abilities, would be involved in some kind of scholarly, creative, or learning project.

4. I also wish, as I have mentioned above, that we could make a genuinely united effort to help students graduate efficiently.

5. I wish that we could make continuing efforts to have writing experiences in almost all of our classes. I would also like our classes to include some kind of library activity. In most of our fields, students should expect that the library will join their professors as primary sources of information and learning.

6. I wish that subject-matter departments would join more fully with the College of Education in the preparation of public school teachers. As a smaller percentage of potential LDS students can attend BYU, one of the best ways to extend our influence is to prepare a large number of teachers who hold our values. But too often we separate subject matter mastery from learning how to teach. Preparing teachers is a venture in which far more of us should participate. I share Alan Keele’s vision that all BYU graduates, because they will be teachers in one context or another, should leave here having had some basic experience with teaching.

7. I wish that we could become more sensitive to those who are different. Our quest for community and unity does not imply that we will ever be exactly the same. It seems apparent that we have become more careful in our conversation and actions, as a whole. But we still hear too many stories of insensitive (and perhaps illegal) questions asked in hiring interviews, careless remarks made in the classroom or hallways, stereotypes perpetuated in recommendations for majors, and lack of understanding shown for special circumstances and disabilities. All of us could probably improve our skills in this respect, but increased goodwill would be an effective beginning point.

Finally, I wish that we would repent. I don’t say this because I feel that we’re off track or slipping away from basic principles. I’ve already said that I believe the current faculty are the best people I have ever had the opportunity to associate with. I say it because of the cleansing and unifying effects of repentance. And I say it under personal motivation. There are probably good reasons why the old hymn, “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing” is no longer in our hymnbook. But there is one line in that song that crosses my mind almost as often as any I have ever sung: “Oh to grace how great a debtor, daily I’m constrained to be.” Facing life with my shortcomings, my awkwardness, my coming short of the glory, and my weaknesses would be very difficult had I never experienced the healing power of that change that has been enabled through God’s Son. And I’ve found that couples, families, and groups can likewise be healed. The Book of Mormon and other scriptures even present us examples of repenting communities. I like to imagine this campus if we were to be as the followers of King Benjamin and ask in unity for forgiveness.

May God bless our university that it may continue to play its important role in furthering his kingdom, I pray in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

| 1949 | 1992 |

| Texas Mines | UTEP |

| Pacific Fleet | San Diego State |

| San Jose State | UCLA |

| Utah | Hawaii |

| Arizona State | Utah State |

| Denver | Fresno State |

| Wyoming | Wyoming |

| Utah State | Notre Dame |

| Colorado A&M | Penn State |

| Montana | New Mexico |

| Pepperdine | Air Force |

| Utah | |

| ACT** | ||

| Fall 1992 | 26.7 | |

| Fall 1991 | 26.1 | |

| Fall 1990 | 25.7 | |

| Fall 1989 | 24.7 | |

| ** Students Admitted | ||

| * Old ACT (would be 25.7 on new ACT) | ||

| * Students Enrolled | |||

| 1991 NATIONAL MERIT SCHOLARSHIPS AWARDED | ||

| Rank | Award | School |

| 1 | 292 | Harvard/Radcliffe Colleges |

| 2 | 246 | Rice University |

| 3 | 210 | University of Texas, Austin |

| 4 | 159 | Stanford University |

| 5 | 154 | Texas A&M University |

| 6 | 144 | Yale University |

| 7 | 107 | Princeton University |

| 8 | 105 | Northwestern University |

| 9 | 102 | Ohio State University |

| 10 | 100 | Brigham Young University |

| 10 | 100 | Duke University |

| 10 | 100 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| 13 | 96 | University of Chicago |

| 13 | 96 | University of Florida |

| 15 | 90 | University of California, Los Angeles |

| 16 | 86 | Carleton College |

| 17 | 83 | Georgia Institute of Technology |

| 18 | 75 | University of New Orleans |

| 19 | 74 | Virginia Polytechnic Institute |

| 20 | 73 | University of Oklahoma |

| 1. University of California, Los Angeles | ||

| 2. University of California, Berkeley | ||

| 3. Brigham Young University | ||

| 4. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor | ||

| 5. Cornell University | ||

| 6. University of Illinois, Urbana | ||

| 7. University of Virginia | ||

| 8. University of Florida | ||

| 9. Stanford University | ||

| 10. University of California, San Diego | ||

| 11. Harvard/Radcliffe | ||

| 12. University of Pennsylvania | ||

| 13. University of Texas, Austin | ||

| 14. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill | ||

| 15. Duke University | ||

| 16. Northwestern University | ||

| 17. Virginia Polytechnic Inst. & State Univ. | ||

| 18. University of California, Irvine | ||

| 19. Yale University | ||

| 20. Massachusetts Institute of Technology | ||

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

Todd A. Britsch was an academic vice president at Brigham Young University when this address was delivered at the Thursday second faculty general session of the BYU Annual University Conference on 25 August 1992.