The combined doctrine of God’s foreknowledge and of foreordination is one of the doctrinal roads least traveled by, yet these clearly underline how very long and how perfectly God has loved us and known us with our individual needs and capacities.

Thank you very much, President Oaks; and thank you, sisters, for that lovely music. This is always a great experience for any of us to have.

Often, when speaking to student leaders in higher education, I have used the analogy that—in a university—the faculty, staff, and administration are like the natives, and the students are like the tourists. In many ways, a recurring devotional speaker is more like one of the natives. Even so, I thank President Oaks for once again extending this precious privilege to me. You may conclude today, however, that I am becoming more like a tourist, since I shall try to cover two topics in order to make the most of these fleeting moments.

Discipleship includes good citizenship; and in this connection, if you are careful students of the statements of the modern prophets, you will have noticed that with rare exceptions—especially when the First Presidency has spoken out—the concerns expressed have been over moral issues, not issues between political parties. The declarations are about principles, not people, and causes, not candidates. On occasions, at other levels in the Church, a few have not been so discreet, so wise, or so inspired.

But make no mistake about it, brothers and sisters; in the months and years ahead, events will require of each member that he or she decide whether or not he or she will follow the First Presidency. Members will find it more difficult to halt longer between two opinions (see 1 Kings 18:21).

President Marion G. Romney said, many years ago, that he had “never hesitated to follow the counsel of the Authorities of the Church even though it crossed my social, professional, or political life” (CR, April 1941, p. 123). This is a hard doctrine, but it is a particularly vital doctrine in a society which is becoming more wicked. In short, brothers and sisters, not being ashamed of the gospel of Jesus Christ includes not being ashamed of the prophets of Jesus Christ.

We are now entering a period of incredible ironies. Let us cite but one of these ironies which is yet in its subtle stages: we shall see in our time a maximum if indirect effort made to establish irreligion as the state religion. It is actually a new form of paganism that uses the carefully preserved and cultivated freedoms of Western civilization to shrink freedom even as it rejects the value essence of our rich Judeo-Christian heritage.

M. J. Sobran wrote recently:

The Framers of the Constitution . . . forbade the Congress to make any law “respecting” the establishment of religion, thus leaving the states free to do so (as several of them did); and they explicitly forbade the Congress to abridge “the free exercise” of religion, thus giving actual religious observance a rhetorical emphasis that fully accords with the special concern we know they had for religion. It takes a special ingenuity to wring out of this a governmental indifference to religion, let alone an aggressive secularism. Yet there are those who insist that the First Amendment actually proscribes governmental partiality not only to any single religion, but to religion as such; so that tax exemption for churches is now thought to be unconstitutional. It is startling [he continues] to consider that a clause clearly protecting religion can be construed as requiring that it be denied a status routinely granted to educational and charitable enterprises, which have no overt constitutional protection. Far from equalizing unbelief, secularism has succeeded in virtually establishing it.

[He continues:] What the secularists are increasingly demanding, in their disingenuous way, is that religious people, when they act politically, act only on secularist grounds. They are trying to equate acting on religion with establishing religion. And—I repeat—the consequence of such logic is really to establish secularism. It is in fact, to force the religious to internalize the major premise of secularism: that religion has no proper bearing on public affairs. [Human Life Review, Summer 1978, pp. 51–52, 60–61]

Brothers and sisters, irreligion as the state religion would be the worst of all combinations. Its orthodoxy would be insistent and its inquisitors inevitable. Its paid ministry would be numerous beyond belief. Its Caesars would be insufferably condescending. Its majorities—when faced with clear alternatives—would make the Barabbas choice, as did a mob centuries ago when Pilate confronted them with the need to decide.

Your discipleship may see the time come when religious convictions are heavily discounted. M. J. Sobran also observed, “A religious conviction is now a second-class conviction, expected to step deferentially to the back of the secular bus, and not to get uppity about it” (Human Life Review, Summer 1978, p. 58). This new irreligious imperialism seeks to disallow certain of people’s opinions simply because those opinions grow out of religious convictions. Resistance to abortion will soon be seen as primitive. Concern over the institution of the family will be viewed as untrendy and unenlightened.

In its mildest form, irreligion will merely be condescending toward those who hold to traditional Judeo-Christian values. In its more harsh forms, as is always the case with those whose dogmatism is blinding, the secular church will do what it can to reduce the influence of those who still worry over standards such as those in the Ten Commandments. It is always such an easy step from dogmatism to unfair play—especially so when the dogmatists believe themselves to be dealing with primitive people who do not know what is best for them. It is the secular bureaucrat’s burden, you see.

Am I saying that the voting rights of the people of religion are in danger? Of course not! Am I saying, “It’s back to the catacombs?” No! But there is occurring a discounting of religiously-based opinions. There may even be a covert and subtle disqualification of some for certain offices in some situations, in an ironic “irreligious test” for office.

However, if people are not permitted to advocate, to assert, and to bring to bear, in every legitimate way, the opinions and views they hold that grow out of their religious convictions, what manner of men and women would they be, anyway? Our founding fathers did not wish to have a state church established nor to have a particular religion favored by government. They wanted religion to be free to make its own way. But neither did they intend to have irreligion made into a favored state church. Notice the terrible irony if this trend were to continue. When the secular church goes after its heretics, where are the sanctuaries? To what landfalls and Plymouth Rocks can future pilgrims go?

If we let come into being a secular church shorn of traditional and divine values, where shall we go for inspiration in the crises of tomorrow? Can we appeal to the rightness of a specific regulation to sustain us in our hours of need? Will we be able to seek shelter under a First Amendment which by then may have been twisted to favor irreligion? Will we be able to rely for counterforce on value education in school systems that are increasingly secularized? And if our governments and schools were to fail us, would we be able to fall back upon the institution of the family, when so many secular movements seek to shred it?

It may well be, as our time comes to “suffer shame for his name” (Acts 5:41), that some of this special stress will grow out of that portion of discipleship which involves citizenship. Remember that, as Nephi and Jacob said, we must learn to endure “the crosses of the world” (2 Nephi 9:18) and yet to despise “the shame of [it]” (Jacob 1:8). To go on clinging to the iron rod in spite of the mockery and scorn that flow at us from the multitudes in that great and spacious building seen by Father Lehi, which is the “pride of the world,” is to disregard the shame of the world (1 Nephi 8:26–27, 33; 11:35–36). Parenthetically, why—really why—do the disbelievers who line that spacious building watch so intently what the believers are doing? Surely there must be other things for the scorners to do—unless, deep within their seeming disinterest, there is interest.

If the challenge of the secular church becomes very real, let us, as in all other human relationships, be principled but pleasant. Let us be perceptive without being pompous. Let us have integrity and not write checks with our tongues which our conduct cannot cash.

Before the ultimate victory of the forces of righteousness, some skirmishes will be lost. Even these, however, must leave a record so that the choices before the people are clear and let others do as they will in the face of prophetic counsel. There will also be times, happily, when a minor defeat seems probable, that others will step forward, having been rallied to righteousness by what we do. We will know the joy, on occasion, of having awakened a slumbering majority of the decent people of all races and creeds—a majority which was, till then, unconscious of itself.

Jesus said that when the fig trees put forth their leaves “summer is nigh” (Matthew 24:32). Thus warned that summer is upon us, let us not then complain of the heat.

Have I come today only to add one more to the already long list of special challenges faced by you and me? Not really. I have also come to say to you that God, who foresaw all challenges, has given to us a precious doctrine which can encourage us in meeting this and all other challenges.

The combined doctrine of God’s foreknowledge and of foreordination is one of the doctrinal roads least traveled by, yet these clearly underline how very long and how perfectly God has loved us and known us with our individual needs and capacities. Isolated from other doctrines or mishandled, though, these truths can stoke the fires of fatalism, impact adversely upon our agency, cause us to focus on status rather than service, and carry us over into predestination. President Joseph Fielding Smith once warned:

It is very evident from a thorough study of the gospel and the plan of salvation that a conclusion that those who accepted the Savior were predestined to be saved no matter what the nature of their lives must be an error. . . . Surely Paul never intended to convey such a thought. [The Improvement Era, May 1963, pp. 350–51]

Paul, you will recall, brothers and sisters, stressed running the life’s race the full distance; he did not intend a casual Christianity in which some had won the race even before the race had started.

Yet, though foreordination is a difficult doctrine, it has been given to us by the living God, through living prophets, for a purpose. It can actually increase our understanding of how crucial this mortal estate is and it can encourage us in further good works. This precious doctrine can also help us to go the second mile because we are doubly called.

In some ways, our second estate, in relationship to our first estate, is like agreeing in advance to surgery. Then the anesthetic of forgetfulness settles in upon us. Just as doctors do not de-anesthetize a patient in the midst of authorized surgery to ask him again if the surgery should be continued, so, after divine tutoring, we agreed once to come here and to submit ourselves to certain experiences and have no occasion to revoke that decision.

Of course, when we mortals try to comprehend, rather than merely accept, foreordination, the result is one in which finite minds futilely try to comprehend omniscience. A full understanding is impossible; we simply have to trust in what the Lord has told us, knowing enough, however, to realize that we are not dealing with guarantees from God but extra opportunities—and heavier responsibilities. If those responsibilities are in some ways linked to past performance or to past capabilities, it should not surprise us.

The Lord has said,

There is a law, irrevocably decreed in heaven before the foundations of this world, upon which all blessings are predicated—

And when we obtain any blessing from God, it is by obedience to that law upon which it is predicated. [D&C 130: 20–21]

This is an eternal law, brothers and sisters—it prevailed in the first estate as well as in the second. It should not disconcert us, therefore, that the Lord has indicated that he chose some individuals before they came here to carry out certain assignments and, hence, these individuals have been foreordained to those assignments. “Every man who has a calling to minister to the inhabitants of the world was ordained to that very purpose in the Grand Council of Heaven before the world was. I suppose that I was ordained to this very office in that Grand Council” (Joseph Fielding Smith, comp., Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, p. 365).

Foreordination is like any other blessing—it is a conditional bestowal subject to our faithfulness. Prophesies foreshadow events without determining the outcomes, because of a divine foreseeing of outcomes. So foreordination is a conditional bestowal of a role, a responsibility, or a blessing which, likewise, foresees but does not fix the outcome.

There have been those who have failed or who have been treasonous to their trust such as David, Solomon, Judas. God foresaw the fall of David, but was not the cause of it. It was David who saw Bathsheba from the balcony and sent for her. But neither was God surprised by such a sad development. God foresaw, but did not cause, Martin Harris’s loss of certain pages of the translated Book of Mormon; God made plans to cope with that failure over fifteen hundred years before it was to occur (see D&C 10 and Words of Mormon).

Thus foreordination is clearly no excuse for fatalism or arrogance or the abuse of agency. It is not, however, a doctrine that can simply be ignored because it is difficult. Indeed, deep inside the hardest doctrines are some of the pearls of greatest price. The doctrine pertains not only to the foreordination of the prophets, but to each of us. God—in his precise assessment, beforehand, as to those who will respond to the words of the Savior and the prophets—is a part of the plan. From the Savior’s own lips came these words: “I am the good shepherd, and know my sheep, and am known of mine” (John 10:14). Similarly the Savior said, “My sheep hear my voice, and I know them, and they follow me” (John 10:27). And further in this dispensation, he declared, “And ye are called to bring to pass the gathering of mine elect; for mine elect hear my voice and harden not their hearts” (D&C 29:7).

This responsiveness could not have been gauged without divine foreknowledge concerning all of us mortals and our response, one way or another, to the gospel. God’s foreknowledge is so perfect it leaves the realm of prediction and enters the realm of prophecy.

The foreseeing of those who would accept the gospel in mortality, gladly and with alacrity, is based upon their parallel responsiveness in the premortal world. No wonder the Lord could say as he did to Jeremiah, “Before I formed thee in the belly I knew thee; . . . and I ordained thee a prophet unto the nations” (Jeremiah 1:5). Paul, when writing to the saints in Rome, said, “God hath not cast away his people which he foreknew” (Romans 11:2). Paul also said of God that “he hath chosen us in him before the foundation of the world” (Ephesians 1:4).

The Lord, who was able to say to his disciples, “Cast the net on the right side of the ship,” knew beforehand there was a multitude of fishes there (John 21:6). If he knew beforehand the movements and whereabout of fishes in the little Sea of Tiberias, should it offend us that he knows beforehand which mortals will come into the gospel net?

It does no violence even to our frail human logic to observe that there cannot be a grand plan of salvation for all mankind, unless there is also a plan for each individual. The salvational sum will reflect all its parts. Once the believer acknowledges that the past, present, and future are before God simultaneously—even though we do not understand how—then the doctrine of foreordination may be seen somewhat more clearly. For instance, it was necessary for God to know how the economic difficulties and crop failures of the Joseph Smith, Senior, family in New England would move this special family to Cumorah country where the Book of Mormon plates were buried. God’s plans could scarcely have so unfolded if—willy-nilly—the Smiths had been born Manchurians and if, meanwhile, the plates had been buried in Belgium!

The Lord would need to have perfect comprehension of all the military and political developments, including those now underway in the Middle East—which, when they unfold, will combine to bring to pass a latter-day condition in which “all nations” will be gathered against Jerusalem to battle (Zechariah 14:2–4). It should not surprise us that the Lord who notices the fall of each sparrow and the hair from every head would know centuries before how much money Judas would receive—thirty pieces of silver—at the time he betrayed the Savior (Matthew 26:15; 27:3; Zechariah 11:12).

Quite understandably, the manner in which things unfold seems to us mortals to be so natural. Our not knowing what is to come (in the perfect way that God knows) thus preserves our free agency completely. When, through a process we call inspiration and revelation, we are permitted at times to tap that divine databank, we are accessing, for the narrow purposes at hand, the knowledge of God. No wonder that experience is so unforgettable!

There are clearly special cases of individuals in mortality who have special limitations in life, which conditions we mortals cannot now fully fathom. For all we now know, the seeming limitations may have been an agreed-upon spur to achievement—a “thorn in the flesh.” Like him who was blind from birth, some come to bring glory to God (John 9:1–3). We must be exceedingly careful about imputing either wrong causes or wrong rewards to all in such circumstances. They are in the Lord’s hands, and he loves them perfectly. Indeed, some of those who have required much waiting upon in this life may be waited upon again by the rest of us in the next world—but for the highest of reasons.

Thus, when we are elected to certain mortal chores, we are elected “according to the foreknowledge of God the Father” (1 Peter 1:2). When Abraham was advised that he “was chosen before he was born,” and that he was among the “noble and great ones” (Abraham 3:22–23), we received a marvelous insight. Through the revelation given to us by the prophet Joseph F. Smith we read that “The Prophet Joseph Smith, . . . Hyrum Smith, Brigham Young, John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, and other choice spirits” were also reserved by God “to come forth in the fullness of times to take part in laying the foundations of the great latter-day work” (JFS Vision 53). These individuals are among the rulers whom Abraham had described to him centuries earlier by God. They were to be “rulers in the Church of God” (JFS Vision 55), not necessarily rulers in secular kingdoms. Thus those seen by Abraham were the Pauls, not the Caesars; the Spencer W. Kimballs, not the Churchills. Wise secular leaders do much lasting and commendable good; but as Paul observed to the saints in Corinth, as the world measured greatness and wisdom “not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble, are called” (1 Corinthians 1:26).

President Joseph Fielding Smith wrote: “In regard to the holding of the priesthood in preexistence, I will say that there was an organization there just as well as an organization here, and men there held authority. Men chosen to positions of trust in the spirit world held priesthood” (Doctrines of Salvation 3:81). Alma speaks about foreordination with great effectiveness and links it to the foreknowledge of God and, perhaps, even to our previous performance (Alma 13:3–5). The omniscience of God made it possible, therefore, for him to determine the boundaries and times of nations (Acts 17:26; Deuteronomy 32:8).

Elder Orson Hyde said of our life in the premortal world, “We understood things better there than we do in this lower world.” Elder Hyde also surmised as to the agreements we made there as follows: “It is not impossible that we signed the articles thereof with our own hands,—which articles may be retained in the archives above, to be presented to us when we rise from the dead, and be judged out of our own mouths, according to that which is written in the books.” Just because we have forgotten, said Elder Hyde, “our forgetfulness cannot alter the facts” (Brigham Young, Journal of Discourses 7:314–15). Brothers and sisters, the degree of detail involved in the covenants and promises we participated in at that time may be a much more highly customized thing than many of us surmise. Yet, on occasion even with our forgetting, there may be inklings. President Joseph F. Smith wrote:

But in coming here, we forget all, that our agency might be free indeed, to choose good or evil, that we might merit the reward of our own choice and conduct. But by the power of the Spirit, in the redemption of Christ through obedience, we often catch a spark from the awakened memories of the immortal soul, which lights up our whole being as with the glory of our former home. [Gospel Doctrines, pp. 13–14; emphasis added]

As indicated earlier, this powerful teaching of foreordination is bound to be a puzzlement in some respects, especially if we do not have faith and trust in the Lord. Yet if we think about it, even within our finite framework of experience, it should not startle us. Mortal parents are reasonably good at predicting the behavior of their children in certain circumstances. Of this Elder James E. Talmage wrote:

Our Heavenly Father has a full knowledge of the nature and disposition of each of His children, a knowledge gained by long observation and experience in the past eternity of our primeval childhood; a knowledge compared with which that gained by earthly parents through mortal experience with their children is infinitesimally small. By reason of that surpassing knowledge, God reads the future of child and children, of men individually and of men collectively as communities and nations; He knows what each will do under given conditions, and sees the end from the beginning. His foreknowledge is based on intelligence and reason. He foresees the future as a state which naturally and surely will be; not as one which must be because He has arbitrarily willed that it shall be.—From the author’s Great Apostasy, pp. 19, 20. [Jesus the Christ, p. 29]

Another helpful analogy for students is the reality that universities, including this one, can and do predict with a high degree of accuracy the grades entering students will receive in their college careers based upon certain tests, past performances, and so forth. If mortals can do this with reasonable accuracy (and even with a short span of familiarity and finite data), God, the Father, who knows us perfectly, surely can foresee how we will respond to various challenges. While we often do not rise to our opportunities, God is neither pleased nor surprised. But we cannot say to him later on that we could have achieved if we had just been given the chance! This is all part of the justice of God.

One of the most helpful—indeed very necessary—parallel truths to be pondered when studying this powerful doctrine of foreordination is given in the revelation of the Lord to Moses in which the Lord says, “And all things are present with me, for I know them all” (Moses1:6). God does not live in the dimension of time as do we. Moreover, since “all things are present with” God, his is not simply a predicting based solely upon the past. In ways which are not clear to us, he actually sees, rather than foresees, the future—because all things are, at once, present before him.

In a revelation given to the Prophet Joseph Smith, the Lord described himself as “The same which knoweth all things, for all things are present before mine eyes” (D&C 38:2). From the prophet Nephi we receive the same basic insight in which we, likewise, must trust: “But the Lord knoweth all things from the beginning; wherefore, he prepareth a way to accomplish all his works among the children of men” (1 Nephi 9:6). It was by divine design that Mary became the mother of Jesus. Further, Lucy Mack Smith, who played such a crucial role in the rearing of Joseph Smith, did not come to that assignment by chance.

One of the dimensions of worshipping a living God is to know that he is alive and living in the sense of seeing and acting. He is not a retired God whose best years are past, to whom we should pay a retroactive obeisance, worshipping him for what he has already done. He is the living God who is, at once, in all the dimensions of time—the past and present and future—while we labor constrained by the limitations of time itself.

It is imperative, brothers and sisters, that we always keep in mind the caveats noted earlier, so that we do not indulge ourselves or our whims, simply because of the presence of this powerful doctrine of foreordination, for with special opportunities come special responsibilities and much greater risks. But the doctrine of foreordination properly understood and humbly pursued can help us immensely in coping with the vicissitudes of life. Otherwise, time can tug at us and play so many tricks upon us. We should always understand that while God is never surprised, we often are.

Life episodes can take on a new meaning. For instance, Simon, the Cyrenian, wandered into Jerusalem that very day and was pressed into service by Roman soldiers to help carry the cross of Christ (see Mark 15:21). Simon’s son, Rufus, joined the Church, and was so well thought of by the apostle Paul that the latter mentioned Rufus in his epistle to the Romans, describing him as “chosen in the Lord” (Romans 16:13). Was it, therefore, a mere accident that Simon “who passed by, coming out of the country” (Mark 15:21), was asked to bear the cross of Jesus?

Properly humbled and instructed concerning the great privileges that are ours, we can cope with what seem to be very dark days and difficult developments, because we will have a true perspective about “things as they really are,” and we can see in them a great chance to contribute. Churchill, in trying to rally his countrymen in an address at Harrow School in October of 1941, said to them:

Do not let us speak of darker days; let us speak rather of sterner days. These are not dark days: these are great days—the greatest days our country has ever lived; and we must all thank God that we have been allowed, each of us according to our stations, to play a part in making these days memorable in the history of our race. [Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, p. 923]

Brothers and sisters, so we should regard the dispensation of the fullness of times—even when we face stern challenges and circumstances, “these are great days”! Our hearts need not fail us. We can be equal to our challenges, including the aforementioned challenge of the secular church.

The truth about foreordination also helps us to taste the deep wisdom of Alma, when he said we ought to be content with things that God hath allotted to each of us (Alma 29:3, 4). If, indeed, the things allotted to each of us have been divinely customized according to our ability and capacity, then for us to seek to wrench ourselves free of our schooling circumstances could be to tear ourselves away from carefully matched opportunities. To rant and to rail could be to go against divine wisdom, wisdom in which we may have once concurred before we came here. God knew beforehand each of our coefficients for coping and contributing and has so ordered our lives.

The late President Henry D. Moyle said,

I believe that we, as fellow workers in the priesthood, might well take to heart the admonition of Alma and be content with that which God hath allotted us. We might well be assured that we had something to do with our “allotment” in our preexistent state. This would be an additional reason for us to accept our present condition and make the best of it. It is what we agreed to do. [CR, October 1952, p. 71]

By the way, brothers and sisters, I hasten to add that among the things “allotted” are not included things like a bad temper. The deficiencies of a developmental variety are those we are expected to overcome.

Now, as I prepare to conclude, may I point out what a vastly different view of life the doctrine of foreordination gives to us. Shorn of this perspective, others are puzzled or bitter about life. Without gospel perspective life would be a punishment, not a joy—like trying to play a game of billiards on a table with a rumpled cloth, with a crooked cue and an elliptical billiard ball (from Sir William S. Gilbert’s libretto of The Mikado). (Perhaps the moral of that analogy is that we should stay out of pool halls.) In any event, pessimism does not really reckon with life and the universe as these things “really are.” The disciple will be puzzled at times, too. But he persists. Later he rejoices over how wonderfully things fit together, realizing only then that, with God, things never were apart.

Jacob said that the Spirit teaches us the truth “of things as they really are, and of things as they really will be” (Jacob 4:13). Centuries later Paul said that the “Spirit searcheth . . . the deep things of God” (1 Corinthians 2:10). Of some of these deep things we have spoken today, and of how things really are. Brothers and sisters, in some of those precious and personal moments of deep discovery, there will be a sudden surge of recognition of an immortal insight, a doctrinal déjà vu. We will sometimes experience a flash from the mirror of memory that beckons us forward toward a far horizon.

When in situations of stress we wonder if there is any more in us to give, we can be comforted to know that God, who knows our capacity perfectly, placed us here to succeed. No one was foreordained to fail or to be wicked. When we have been weighed and found wanting, let us remember that we were measured before and we were found equal to our tasks; and, therefore, let us continue, but with a more determined discipleship. When we feel overwhelmed, let us recall the assurance that God will not overprogram us; he will not press upon us more than we can bear (D&C 50:40).

The doctrine of foreordination, therefore, is not a doctrine of repose; it is a doctrine for the second-milers; it can draw out of us the last full measure of devotion. It is a doctrine of perspiration, not aspiration. Moreover, it discourages aspiring, lest we covet, like two early disciples, that which has already been given to another (Matthew 20:20–23). Foreordination is a doctrine for the deep believer and will only bring scorn from the skeptic.

When, as Joseph F. Smith said, we “catch a spark from the awakened memories of the immortal soul,” let us be quietly grateful. And when of great truths we can come to say “I know,” that powerful spiritual witness may also carry with it the sense of our having known before. With rediscovery, what we are really saying is, “I know—again!” No wonder that, so often, real teaching is mere reminding.

God bless you and keep you, my special friends, to the end that you will each carry out all of the assignments given to you so very long ago. You have been measured and found adequate for the challenges that will face you as citizens of the kingdom of God; of that you should have a deep inner assurance. Be true to that trust, as all of us must, I pray in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

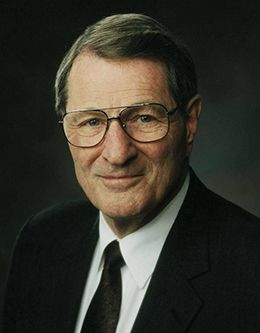

Neal A. Maxwell was a President of the First Quorum of the Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 10 October 1978.