Meekness is needed in order for us to be spiritually successful—whether in matters of the intellect, in the management of power, in the dissolution of personal pride, or in coping with the challenges and routine of life. With meekness, living in “thanksgiving daily” is actually possible even in life’s stern seasons.

Wearing His Yoke

Meekness ranks so low on the mortal scale of things, yet so high on God’s: “For none is acceptable before God, save the meek and lowly in heart” (Moroni 7:44). The rigorous requirements of Christian discipleship cannot be met without the tutoring facilitated by meekness: “Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly” (Matthew 11:29). Jesus, the carpenter, “undoubtedly had experience making yokes” with Joseph (Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, vol. 4 [New York: Abingdon Press, 1962], p. 925), and thus the Savior gave us that marvelous metaphor (see Matthew 11:20). Unlike servitude to sin, by wearing his yoke, we truly learn of the Yoke Master in what is an education for eternity as well as for mortality.

Meekness is needed, therefore, in order for us to be spiritually successful—whether in matters of the intellect, in the management of power, in the dissolution of personal pride, or in coping with the challenges and routine of life. With meekness, living in “thanksgiving daily” is actually possible even in life’s stern seasons (Alma 34:38).

Meanwhile, the world regards the meek as nice but quaint people, as those to be stepped over or stepped on. Nevertheless, the development of this virtue is a stunning thing just to contemplate, especially in a world in which so many others are headed in opposite directions. These next requirements clearly show the unarguable relevance as well as the stern substance of this sweet virtue.

Serious disciples are not only urged to do good but also to avoid growing weary of doing good (see Galatians 6:9 and Helaman 10:5).

They are not only urged to speak the truth but also to speak the truth in love (see Ephesians 4:15).

They are not only urged to endure all things but also to endure them well (see D&C 121:8).

They are not only urged to be devoted to God’s cause but also to be prepared to sacrifice all things, giving, if necessary, the last full measure of devotion (see Lectures on Faith 6:7).

They are not only to do many things of worth but are also to focus on the weightier matters, the things of most worth (see Matthew 23:23).

They are not only urged to forgive but also to forgive seventy times seven (see Matthew 18:21–22).

They are not only to be engaged in good causes, but also they are to be “anxiously engaged” (see D&C 58:27).

They are not only to do right but also to do right for the right reasons.

They are told to get on the strait and narrow path, but then are told that this is only the beginning, not the end (see 2 Nephi 31:19–20).

They are not only to endure enemies but also to pray for them and to love them (see Matthew 5:44).

They are urged not only to worship God but, astoundingly, they are instructed to strive to become like him! (See Matthew 5:48; 3 Nephi 12:48, 27:27.)

In the midst of all these things, they are given a Sabbath day for rest, during which they do the sweetest but often the hardest work of all.

Who else but the truly meek would even consider such a stretching journey?

The preceding enumeration is certainly a verification of the crucial role meekness plays in the lives of serious disciples. Thus, if we really learn of the Savior, it will be by taking the yoke of such experiences upon us.

This is a high-yield, but very severe form of learning. However, there is “no other way.” Moreover, when so yoked, we may then get much more learning than we bargained for. Furthermore, to be spiritually successful, Jesus’ yoke cannot be removed part way down life’s furrow, even after a good showing up to that point; we are to endure well to the end.

The Key to Deepening Discipleship

Did Paul not speak knowingly of the “fellowship of [Christ’s] sufferings” (Philippians 3:10)? Are we not told that meekness is so vital that God actually gives us certain challenges in order to keep us humble (Ether 12:27)? Did not Peter write regarding how Christians should expect to be familiar with fiery trials (1 Peter 4:12)? Furthermore, as the disciple enriches his relationship with the Lord, he is apt to have periodic “public relations” problems with others, being misrepresented and misunderstood. He or she will have to “take it” at times. Meekness, therefore, is a key to deepening discipleship.

In the exchange between Jesus and a righteous young man, we see how one missing quality cannot be fully compensated for, even by other qualities, however praiseworthy.

The young man saith unto him, All these things have I kept from my youth up: what lack I yet?

Jesus said unto him, If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come and follow me.

But when the young man heard that saying, he went away sorrowful: for he had great possessions. [Matthew 19:20–22]

In this instance the missing meekness prevented a submissive response by the young man; this deficiency altered his decision and the consequences flowing there from.

There appears to be “no other way” to learn certain things except through the relevant, clinical experiences. Happily, the commandment “Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart” (Matthew 11:29) carries an accompanying and compensating promise from Jesus—“and ye shall find rest unto your souls.” This is a very special form of rest. It surely includes the rest resulting from the shedding of certain needless burdens: fatiguing insincerity, exhausting hypocrisy, and the strength-sapping quest for recognition, praise, and power. Those of us who fall short, in one way or another, often do so because we carry such unnecessary and heavy baggage. Being thus overloaded, we sometimes stumble and then feel sorry for ourselves.

We need not carry such baggage. However, when we’re not meek, we resist the informing voice of conscience and feedback from family, leaders, and friends. Whether from preoccupation or pride, the warning signals go unnoticed or unheeded. However, if sufficient meekness is in us, it will not only help us to jettison unneeded burdens, but will also keep us from becoming mired in the ooze of self-pity. Furthermore, true meekness has a metabolism that actually requires very little praise or recognition—of which there is usually such a shortage anyway. Most of the time, the sponge of selfishness quickly soaks up everything in sight, including praise intended for others.

Disciples are to make for themselves “a new heart” by undergoing a “mighty change” of heart (Ezekiel 18:31; Alma 5:12–14). Yet we cannot make such “a new heart” while nursing old grievances. Just as civil wars lend themselves to the passionate preservation of ancient grievances, so civil wars within the individual soul—between the natural and the potential man—keep alive old slights and perceived injustices, except in the meek.

Is there not deep humility in the omnicompetent Christ, the majestic Miracle Worker, who acknowledged, “I can of mine own self do nothing” (John 5:30)? Jesus neither misused nor doubted his power, but he was never confused about its source, either. Instead, we mortals—perhaps even when otherwise modest—are sometimes quite willing to display our accumulated accomplishments, as if we had done it all by ourselves. Hence this sobering reminder:

And thou say in thine heart, My power and the might of mine hand hath gotten me this wealth.

But thou shalt remember the Lord thy God: for it is he that giveth thee power to get wealth, that he may establish his covenant which he sware unto thy fathers, as it is this day.[Deuteronomy 8:17–18]

Meekness is especially needed to labor in the Lord’s vineyard, which involves such lowly work—as the world measures worth. No wonder, as one prophet wrote, the laborers in the Lord’s vineyard are comparatively “few.” Moreover, the Lord’s work is not usually performed on a luxuriant landscape, but, said Jacob, in “the poorest spot in all the land of [the] vineyard” (see Jacob 5:21, 70). The world’s Caesars pay little heed to such workers.

Had Jesus not been meek and lowly when “a great multitude with swords and staves” (Mark 14:43) came to take him, he could have resisted his destiny. Led by Judas, there came “thither” that band of men “with lanterns and torches” (John 18:3). So spiritually blind was the multitude, they actually needed lanterns to see and capture the “Light of the World”!

Though he was actually the Creator of this world, the earth being his footstool, Jesus’ willingness to become from birth a person of “no reputation” provides one of the great lessons in human history. He, the leader-servant, who remained of “no reputation” mortally, will one day be he before whom every knee will bow and whose name every tongue will confess (see Philippians 2:10–11). Jesus meekly stayed his unparalleled course.

Brigham Young, who stayed his lesser but very impressive course, knew both the fatigue of leadership and the rest Jesus promised. He counseled those less spiritually secure and more anxious about the outcome:

It is the Lord’s work. I know enough to let the kingdom alone, and do my duty. It carries me, I do not carry the kingdom. I sail in the old ship Zion, and it bears me safely above the raging elements. [JD 11:252]

In our own time, the late Elder LeGrand Richards was heard by some of us to declare that he did not fret about the Church, because it is the Lord’s Church, “so I let him worry about it!”

Wise secular leaders are not strangers to meekness either. The following episode in the life of George Washington involved potential mutiny:

Washington called together the grumbling officers on March 15, 1783. . . . He began to speak—carefully and from a written manuscript, referring to the proposal of “either deserting our Country in the extremest hour of her distress, or turning our Arms against it. . . .” Washington appealed simply and honestly for reason, restraint, patience, and duty—all the good and unexciting virtues.

And then Washington stumbled as he read. He squinted, paused, and out of his pocket he drew some new spectacles.

“Gentlemen, you must pardon me,” he said in apology. “I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind.”

Most of his men had never seen the general wear glasses. Yes, men said to themselves, eight hard years. They recalled the ruddy, full-blooded planter of 1775; now they saw . . .a big, good, fatherly man grown old. They wept, many of those warriors. And the Newburgh plot dissolved. [Bart McDowell, The Revolutionary War: America’s Fight for Freedom (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 1967), pp. 190–91]

The meek leader, having “humbleness of mind” (Colossians 3:12), is not only more easily taught, but he is also freer. Even in routine he is relieved, for instance, of the pressure to be the single or even the chief source of ideas for the group. Nor need he be the sole source of his group’s memory. He lets others, too, report what they see by the light of what Samuel Coleridge called experience and history’s “lantern on the stern.” The meek individual is more concerned with the light on the bow, which shines ahead.

He need not be afraid to praise, lest someone gain on him. He follows the pattern of rejoicing in the achievements of others as shown so effulgently by the Father and the Son. After all, the meek and lowly Leader did not need advance men or paid demonstrators with bands and banners: “Behold, thy King cometh unto thee, meek, and sitting upon . . . a colt” (Matthew 21:5).

True Education

Meekness of mind is not only essential salvationally. It is also vital, of course, if one is to experience true intellectual growth, especially that which heightens his understanding of the great realities of the universe. Such meekness is a friend, not a foe, of true education. Stephen spoke of Moses: “And Moses was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians, and was mighty in words and in deeds” (Acts 7:22). Though Moses was a learned man, he was the most meek man “upon the face of the earth” (Numbers 12:3). So it was that he could and did learn things he “never had supposed” (Moses 1:10).

As the well-educated Paul warned, the indiscriminate or arrogant approach to learning fails to distinguish between chaff and kernels. Therefore, some are proudly “Ever learning, and never able to come to the knowledge of the truth” (2 Timothy 3:7). Unsurprisingly, therefore, great stress is deservedly placed upon the need for intellectual meekness—“humbleness of mind.”

Meekness is thus so much more than a passive attribute that merely deflects discourtesy. Instead, it involves spiritual and intellectual activism: “For Ezra had prepared his heart to seek the law of the Lord, and to do it, and to teach in Israel statutes and judgments” (Ezra 7:10; see also 2 Chronicles 19:3, 20:33). Meek Nephi, in fact, decried the passivity of those who “will not search knowledge, nor understand great knowledge, when it is given unto them in plainness” (2 Nephi 32:7). Alas, most are unsearching—quite content with a superficial understanding or a general awareness of spiritual things (see Alma 10:5–6). This condition may reflect either laziness or, in Amulek’s case, the busyness usually incident to the cares of the world.

Intellectual meekness is a persistent as well as particular challenge. Without it, we are not intellectually open to things that we “never had supposed” (Moses 1:10). Alas, some have otherwise reached provincial and erroneous conclusions and do not really want to restructure their understanding of things. Some wish neither to be shaken nor expanded by new data.

The Chains of Pride

Just as meekness is in all our virtues, so is pride in all our sins. Whatever its momentary and alluring guise, pride, as Henry Fairlie articulately notes, is the enemy—“the first of the sins” (Henry Fairlie, The Seven Deadly Sins Today [Washington, D.C.: New Republic Books, 1978], p. 39).

The meek individual may not, to be sure, always fully decipher what is happening to him or around him. However, even though he does not “know the meaning of all things,” he knows that the Lord loves him (see 1 Nephi 11:17). He may feel overwhelmed, but, unlike the proud, he is not out of control. In fact, in some moments it is important for us to “Be still, and know that [he is] God” (Psalms 46:10). Even articulate discipleship has its side of silent certitude!

The “rest” promised by Jesus to the meek, though not including an absence of adversity or tutoring, does, therefore, give us the special peace that flows from “humbleness of mind.” The meek management of power and responsibility relieves us of the heavy and grinding chains of pride; however glitzed and polished, they are still chains.

Meekness also protects us from the fatigue of being easily offended. There are so many just waiting to be offended. They are so alerted to the possibility that they will not be treated fairly, they almost invite the verification of their expectation! The meek, not on such a fatiguing alert, find rest from this form of fatigue.

Bruising as the tumble off the peak of pride is, it may be necessary at times. Few of us escape at least some of these bruises. Even then, one must next be careful not to continue his descent into the swamp of self-pity. Meekness enables us, after such a tumble, to pick ourselves up—but without putting others down blamefully. Meekness mercifully lets us retain the realistic and rightful impressions of how blessed we are, so far as the fundamental things of eternity are concerned. We are not then as easily offended by the disappointments of the day, of which there seems to be a sufficient and steady supply.

When we are thus spiritually settled, we will likewise be less apt to murmur and complain. Indeed, one of the great risks of murmuring is that we can get too good at it, too clever. We can even acquire too large an audience. Furthermore, what for the murmurer may only be transitory grumbles may become a cause for a hearer that may carry him or her clear out of the Church.

The meek are unconcerned with prideful preeminence, including considerations of scale. The lowly are not exercised, for instance, over quantitative considerations. The Lord put that concern to rest centuries ago.

The Lord did not set his love upon you, nor choose you, because ye were more in number than any people; for ye were the fewest of all people:

But because the Lord loved you, and because he would keep the oath which he had sworn unto your fathers, hath the Lord brought you out with a mighty hand, and redeemed you out of the house of bondmen, from the hand of Pharaoh king of Egypt. [Deuteronomy 7:7–8]

With Ears to Hear

When the Lord declared, “My sheep hear my voice. . . and they follow me” (John 10:27), it was not only an indication of how profound recognition and familiarity would be at work; it also bespoke another role of operational meekness—listening long and humbly enough for such recognition to occur.

This readiness with ears to hear has been needed in all dispensations, but never more than after the Restoration. The “restitution of all things” (Acts 3:21) ended centuries of deprivation, but the Restoration goes sharply against the grain of heedless secular societies. So, while the truths of the Restoration are “had again,” they are useful only “among as many as shall believe” (Moses 1:40–41). Yet those astray include “humble followers of Christ” who err only “because they are taught by the precepts of men” (2 Nephi 28:14). In addition, the adversary’s kingdom “must shake” in order that those who will may be “stirred up unto repentance” (2 Nephi 28:19). The meek understand such realities.

Meekness also contains a readiness that helps us to surmount the accumulated stumbling blocks and rocks of offense; we can make stepping stones of them and achieve a deeper and broader view of life. Obviously, Philip had such readiness and meekness when he recognized Jesus as the Messiah of whom Moses had spoken (John 1:45). Obviously, Paul had the broad view, too, when he described Moses as having foregone, by choice, the favored life in Pharaoh’s court for a life of service to Jesus (Hebrews 11:24–27). Nevertheless, the stones of stumbling and rocks of offense are real. In fact, these offending rocks (see Isaiah 8:14–15) can prove insurmountable, unless we have the facilitating attribute of meekness with its promise of access to the grace of God.

Even if it stood alone as a benefit, one reason for developing greater meekness is to have greater access to the grace of God. The Lord guarantees that his grace is sufficient for the meek (Ether 12:26). Besides, only the meek know how to draw fully upon his assistance anyway.

Meekness comes trailing a cloud of other beneficial considerations. The prophet Mormon (see Moroni 7:43–44) observed that without meekness there can be no faith, hope, or love. Furthermore, the remission of our sins brings additional meekness along with the great gift of the Holy Ghost, or Comforter (Moroni 8:26). These supernal blessings are not to be enjoyed for any length of time except by those who are meek. As to genuine joy, it is received by none “save it be the truly penitent and humble seeker of happiness” (Alma 27:18).

Preliminarily, we cannot even have true faith, except we are meek and lowly in heart (Moroni 7:43–45). Thus we are able to enjoy greater faith, hope, love, knowledge, and reassurance. We will thus know the answer to what Amulek called the “great question” (see Alma 34:5)—whether there really is a rescuing and redeeming Christ. It is by the power of the Holy Ghost that we know that Jesus is the Christ, that he lived and lives. Thus it is the meek who receive the great answers to the “great question,” rejoicing, therefore, over the “great and last sacrifice” (Alma 34:10).

Preparing for Eternity

Since life in the Church illustrates, painfully at times, our own defects, as well as the defects of others, we are bound to be periodically disappointed thereby in ourselves and in others. We cannot expect it to be otherwise in a kingdom where, initially, not only does the net gather “of every kind,” but those of “every kind” are also at every stage of spiritual development (see Matthew 13:47). When people “leave their nets straightway” (see Matthew 4:20 and Mark 1:18), they come as they are—though in the initial process of changing, their luggage reflects their past. Hence, discipleship is a developmental journey that requires shared patience, understanding, and meekness on the part of all who join the caravan. Together we are disengaging from one world and preparing ourselves for another and far better world.

Meekness and patience have a special mutuality. If there were too much swiftness, there could be no long-suffering, no gradual soul-stretching, nor repenting. With too little time to absorb, to assimilate, and to apply the truths already given, our capacities would not be fully developed. Pearls cast before us would go unfound, ungathered, and unsavored. It takes time to prepare for eternity.

For he will give unto the faithful line upon line, precept upon precept; and I will try you and prove you herewith. [D&C 98:12]

I will give unto the children of men line upon line, precept upon precept, here a little and there a little; and blessed are those who hearken unto my precepts, and lend an ear unto my counsel, for they shall learn wisdom; for unto him that receiveth I will give more. [2 Nephi 28:30]

The meek are also less likely to ask amiss in their prayers (see James 4:3). Being less demanding of life to begin with, they are less likely to ask selfishly or to act selfishly.

In so many ways, the wise interplay of our individual agency with God’s loving purposes for us is greatly facilitated by our meekness. Were it not so, we would, at best, offer ourselves pridefully to God, but only as we now are—“Take it or leave it,” an unacceptable offering. The only individual who might have credibly done that instead meekly submitted himself to the Father’s further, shaping will (see Alma 7:11–12).

Meekness could have rescued proud and fearful Judas even after he had left the Last Supper. He could have slipped back in later, quietly and humbly, rejoining his apostolic colleagues, having belatedly determined not to do the dastardly deed. Meekness can rescue us from ourselves even when we are deep in error, even when others have written us off.

The Small View Versus Reality

Meekness enlarges souls, but without hypocrisy. Contrariwise, “littleness of soul” (D&C 117:11) insures that only a small view of reality will be taken. This narrow view prevailed when Cain slew Abel and then gloried and boasted, “Behold, now I am free” (see Moses 5:33). Free? Yes, free to be “a fugitive and a vagabond” in the stretching desert he had made of his own life (Moses 5:39). Both Cain’s desire for Abel’s flocks and his being offended at the acceptance of Abel’s sacrifice played a part in his fall. Moreover, proud Cain “rejected the greater counsel which was had from God” (Moses 5:25).

The small, myopic view also lends itself, in the Lord’s words, to coveting “the drop,” while neglecting “the more weighty matters” (D&C 117:8). In all of our getting and grasping we do not seem to grasp, for instance, the implications of this searching question from the Lord:

For have I not the fowls of heaven, and also the fish of the sea, and the beasts of the mountains? Have I not made the earth? Do I not hold the destinies of all the armies of the nations of the earth? [D&C 117:6]

No wonder the Lord also reminds us acquisitive mortals, “For what is property unto me?” (D&C 117:4).

I, the Lord, stretched out the heavens, and built the earth, my very handiwork; and all things therein are mine. [D&C 104:14]

One day he will share all he has with the meek. For every one else, whatever their temporary possessions, the Creator’s reversion clause will take effect.

The meek likewise understand still another reality—that, as much as or more than anything else, it is our faith and patience that are to be tried (see Mosiah 23:21). Our trials, however, occur in the context of this precious promise:

Thus God has provided a means that man, through faith, might . . . becometh a great benefit to his fellow beings. [Mosiah 8:18]

Before he became encrusted with power, Saul knew a time when he was “little in [his] own sight” (1 Samuel 15:17). However, meekness did not stay on as his uninvited guest; it quickly departs where it’s not wanted. It is so easy for us to become puffed up and to be condescending to others. One devoted public servant who ably served several British Prime Ministers as their private secretary, observed:

Vanity is a failing common to Prime Ministers. . . ; and I suppose it is natural in view of the adulation they receive but to which they are not, like Kings, accustomed. [John Colville, The Fringes of Power (New York and London: W. W. Norton and Company, 1985), p. 79]

“Meek and Lowly” Men

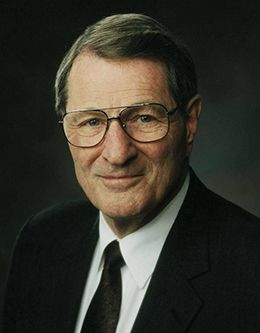

Fortunately, we have fine examples of meekness to help us, and I need go no farther than my own Quorum.

The Acting President of the Council of the Twelve, President Howard W. Hunter, is a meek man. He once refused a job he needed as a young man because it would have meant another individual would have lost his job. This is the same lowly man, when I awakened after a weary and dusty day together with him on assignment in Egypt, who was quietly shining my shoes, a task he had hoped to complete unseen. Meekness can be present in the daily and ordinary things.

The President of the Twelve, President Marion G. Romney, is also a meek man. The scene was a fast and testimony meeting in his home ward, just after he was first sustained by the Church as a Counselor in the First Presidency. Touchingly, meekly, and tenderly, President Romney said to his beloved neighbors that he could obediently sustain whomever the Lord called, even when the person called was Marion G. Romney. All of us who were there loved him all the more! Meekness can be there even in moments of deserved recognition.

Sir Thomas More was a victim of injustice and irony. Generously and meekly, just as he was about to be martyred, he said:

Paul . . . was present, and consented to the death of St. Stephen, and kept their clothes that stoned him to death, and yet be they [Stephen and Paul] now both twain Holy Saints in heaven, and shall continue there friends for ever, so I verily trust and . . . pray, that though your lordships have now here in earth been judges to my condemnation, we may yet hereafter in heaven merrily all meet together, to our everlasting salvation. [Anthony Kenny, Thomas More (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 88]

Meekness can be present in moments of injustice and crisis at the hands of lesser men.

Jesus meekly endured the lesser spiritual maturity in the Twelve and in his other disciples. He endured this while helping remedy it. He did this without condescension, without despairing, without cynicism, and without murmuring. We have only to look at his prayers to the Father for and in behalf of his disciples to see how perfect his love is (see John 17). Indeed, when his followers deserved censure, they received teaching. Though he sometimes spoke reproving truth to them, Christ spoke the truth in love (Ephesians 4:15).

What a contrast to us mortals! At times we withhold reproof, time, talent, and knowledge from others in order to retain a seeming advantage, an edge. No wonder there could never be compliance with consecration without meekness. For consecration seeks to share—not to withhold.

The Serious Disciple

The full witness often does not come “until after the trial of your faith” (Ether 12:6). Those trials may be very focused. President Lorenzo Snow once said to the Twelve of his day, “Every one of us who has not already had the experience must yet meet it of being tested in every place where we are weak” (Abraham H. Cannon journal, April 9, 1890). Indeed, did not the Lord specifically promise the meek that he would make “weak things become strong unto them” (Ether 12:27)?

In those instances of available record, the Lord has displayed much gentleness and tenderness in his tutoring of meek individuals. The pattern usually involves his disclosing more about himself, about his work, and what taking his yoke upon us will mean. He thus expands the horizons of the person being tutored. The Lord likewise usually assigns the individual a portion of the Lord’s work to do. The disciple’s course involves more lab and fieldwork than lectures.

For the serious disciple, the greater his knowledge, the greater his meekness. The more he strives to become like Jesus and the more he wishes to declare his gospel, the more he rejoices exceedingly when Christ’s message is heeded, as did the outreaching sons of Mosiah, who rejoiced that no human soul would perish if they received the gospel.

Unsurprisingly, the Lord’s angelic messengers also reflect meek friendship, as did the angel that spoke with Alma:

Blessed art thou, Alma; therefore, lift up thy head and rejoice, for thou hast great cause to rejoice; for thou hast been faithful in keeping the commandments of God from the time which thou receivest thy first message from him. Behold, I am he that delivered it unto you. [Alma 8:15]

The meek are such caring realists!

These patterns of gentleness and tenderness are too striking to be accidental. They are even reflected in the voice of the Lord, even in its very timbre, for his is a pleasant, mild, and gentle voice:

. . . it was not a voice of thunder, neither was it a voice of a great tumultuous noise, but behold, it was a still voice of perfect mildness, as if it had been a whisper, and it did pierce even to the very soul—[Helaman 5:30]

. . . yea, a pleasant voice, as if it were a whisper. [Helaman 5:46]

. . . it was not a harsh voice neither was it a loud voice; nevertheless, and notwithstanding it being a small voice it did pierce them that did hear to the center. [3 Nephi 11:3]

The stunning episode atop the Mount of Transfiguration doubtless involved the same pattern of further disclosing, preparing, reassuring, instructing, and blessing with regard to Peter, James, and John (see Matthew 17:1–9). Though we do not have all of the sacred particulars of what occurred there, Peter, James, and John received special blessings and insights as a result of being atop the Mount of Transfiguration. It was good for them to have been there (Matthew 17:4), but they would not have been in those supernal circumstances except they were sufficiently meek, though further trials and tutoring still lay ahead.

The pattern of calling, blessing, expanding, reassuring, and endowing are reflective of the generosity as well as the gentleness of God our Father and his son, Jesus Christ!

Astonishingly, to those who have eyes to see and ears to hear, it is clear that the Father and the Son are giving away the secrets of the universe! If only you and I can avoid being offended by their generosity.

If we would be with them, whether on a mountaintop or forever, we should ponder anew these sobering words: “For none is acceptable before God, save the meek and lowly in heart” (Moroni 7:44). Besides, can we ever truly and fully accept ourselves until we become more like them?

That you and I may be meek disciples is my prayer on this special day. I salute you as servants of the Lord Jesus Christ and thank him for being our yoke master, for being meek and lowly, and inviting us to learn of him. It is the only way we can truly learn of him—to take his yoke upon us. I say this in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Neal A. Maxwell was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 21 October 1986.