The Authority of Personality, Competence, and Character

of the Presidency of the First Quorum of the Seventy

August 23, 1988

of the Presidency of the First Quorum of the Seventy

August 23, 1988

We are authority figures, and our outreach, or our interest—or our lack of it—may influence these of little experience but great capacity to learn.

I would like to employ President Holland’s services in reading anything I write. It sounds good coming from him! Indeed, I felt like Victor Hugo for a moment, who, watching one of his plays, apparently oblivious for the moment to his surroundings, stood and shouted, “Hernani!” and took off his hat to the author of the great play.

I was introduced at a graduation exercise this year in terms of periods of service—about the way Brother Holland did—by a Regional Representative who wasn’t content with that but added I had been the speaker at his high school graduation. I could only reply to that by saying I was the only thirteen-year-old graduation speaker I had ever heard of.

Lest it be forgotten, Brother Shumway, I sat thinking about a conversation I had with someone as we watched some of the Gina Bachauer piano performances. That person said, “You really can’t tell what a pianist looks like.” They come in obviously different sizes and shapes and hair styles and the rest. I remembered it tonight because it permits me to say that, this being true, we know what one sounds like. The music was magnificent, and we commend you.

I am grateful to be in this fourth temple I have been in during the last twenty-four hours—this temple of learning, appropriately thought of. I was in the Salt Lake Temple this morning, where nine new temple presidents and their wives were being greeted and a lovely seminar was begun. Yesterday I had the great blessing of being in our home—there is no more sacred place to me—and I also had the blessing of working for a time outdoors under the shadow of the Wasatch Mountains, in that great temple. I used a saw and a rake and a shovel and, as part of my outdoor experience, spent some time trying to separate a honeysuckle vine from an Oregon grape bush. (And I can report to you that for at least part of that time I was patient and pleasant!)

In all those places I sat thinking or stood thinking or swung thinking. One strange set of thoughts came. Regarding my being in this temple of learning, I thought about three newspaper items that over the years have segregated themselves from tens of thousands in memory. They are humorous to me. I have discovered they are not all humorous to everyone.

One I read in the Arkansas Gazette was about the man who lost his wedding band while fishing at Lee’s Creek on September 27, 1981. He was horrified; he searched, went home, wept with his wife over the loss of this treasure, but he just couldn’t find it. However, said the newspaper, he went back a year later to the same place on the same date. While fishing in Lee’s Creek he caught an eighteen- to twenty-inch trout. While cutting it open with his sharp knife, his knife hit something solid. It was his thumb!

Another has to do with the place we served our missions, some of them, and the staid London Times, which never ever admits a mistake on the theory that it never makes one. Nevertheless, it printed the obituary of a certain man one day who called and said there wasn’t a word of truth in it. “Oh, yes,” said the secretary on the line, “and from where are you calling?”

The third is strictly relevant to this place. I read not the original article but a letter to the editor about an article in an Arizona newspaper. Apparently a public official, perhaps the governor, was under obligation to release a number of workers, with budgetary constraints prompting him. The newspaper had printed the story with a headline that said: “Whom Shall Be Fired First?” The letter to the editor calling attention to that and repeating it, said, “I read your article and your headline ‘Whom Shall Be Fired First?’ My answer is this: Whom wrote the headline? Him shall be fired first.”

This is a university, and presumably one of the things expected of a university is that its personnel know the time to use who or whom. But of course there are a lot more important things a university ought to represent, and you have been, I am sure, in these days and months and years of your association, reminded of some of them because they have been clearly declared, generally understood, and often related. As a kind of foundation, I would like to repeat three of them as I understand them, and if there is error in my comprehension, I will be pleased to be corrected.

1. BYU is a university that has as the basis of its educational goals scholastic success for its students and their spiritual/religious/ moral development, which objective applies also to all who are connected with the school in any way, in any assignment or relationship. For this it was founded, organized, funded, staffed, nurtured, and built into a great, growing university. Of course, there is nothing in this objective that vitiates in any way or compromises the university’s high scholastic aim and the effort to achieve it; rather, it serves to define those particular objectives. This school is meant to be a bastion of decency in a coarsening world where there is continual corrosion of moral and spiritual sensibilities.

2. BYU retains a commitment to the principle, as I understand it, of in loco parentis, “in the place of a parent.” In an educational climate in which that principle is largely abandoned now, BYU cares, as a true parent should, about the whole lives of those who come to study here—their educational preparation, the nature and quality of their lifestyle, and the enhancement of their sensitivity and the quality of spirit that relates to the inner world of each individual. BYU cares what kind of people they are. It cares what kind of people they are. And that, after all, is what matters—not slogans, not even high and holy objectives. BYU stands in the place of a parent.

3. Those who serve here in any capacity—administration, faculty, staff, all others—represent the school in their various positions and for this reason undertake a solemn trust. The pipe fitter and professor as well as the policeman represent authority—the attendant as well as the administrator, the carpenter and the controller, the gardener and the geologist. Each is under obligation to honestly support in their service and their lives the purpose, the policies, and the standards that are the reason for this university’s existence. And it is about this authority and responsibility and opportunity, which each of you bears, that I would speak a few minutes this evening.

I plead with you to consider thoughtfully what I am about to say, not because I say it but because I believe from a lifetime of observation and consideration that it is true.

For years on Temple Square, where I had some of my sweetest and holiest and happiest experiences, I observed with amusement at first, surprise somewhat, and then with wonder at the number of tourists, guests in our city and on our grounds—a few of them every day—who avoided the well-dressed guides and the receptionists with their identifying badges and instead quietly cornered a gardener planting flowers or a plumber fixing a fountain to ask their religious or curiosity questions. Somehow they wanted to avoid what they conceived to be a professional person, who should answer and is ready to and probably will give you a lot more than you want to know, and went to hear what they hoped to hear from the “regular” people how they felt about their religion.

I remember reading as a youngster the story of The Grand Hotel. A movie was made that was famous for many years. I only remember one thing about it. It was that when the secret of the Grand Hotel, the greatest hostelry on earth, became evident, it was that every person who worked there—from the custodian, the gardener, through the food services people to the manager of the hotel—thought his or her job was the most important one in the establishment and that it could not succeed if they didn’t do their job.

Well, let me look at you tonight as authority figures. And, on the premise which is to me much more than that, on the experience and conviction that people like to listen to important things or like to get a viewpoint or feeling from those who are not professionally, as it were, involved in the exercise (though that doesn’t cut out those who are), I invite you to consider these simple ideas.

Authority is a very important subject among us and very basic in our religion, but I do not wish to talk about it in the conventional sense now. There are several varieties of authority. It is important to understand the diversity of them and their meaning and the use and effect of each.

First there is the authority of position, the one I suppose we normally think about, of appointed power, of leadership and supervision under authorization. This kind of authority may be exercised because one is there, empowered to act, and with the force of that position may control or significantly affect others. Such authority has the capacity to invoke consequences if its direction is not followed, if adherence and obedience are not forthcoming. This authority is recognized as having the power to get its way.

Beyond offices of appointment and power there are other forms of authority that do not depend for their efficacy, for their success, on command of the power of position. Although the kind of authority we perhaps generally think of when we allude to the word of the concept is this power of position, I want to talk about some other kinds.

Before I do, though, permit me to say that “position” authority is clearly defined in a verse of scripture where a centurion approaching the Savior asks the Lord to help his servant who suffers from a terrible illness. Christ is agreeable to go with him to the centurion’s home. The latter says no—that would be asking too much. “But speak the word only, and my servant shall be healed” (Matthew 8:8). This man, in the course of that experience, describes himself:

For I am a man under authority, having soldiers under me: and I say to this man, Go, and he goeth; and to another, Come, and he cometh; and to my servant, Do this, and he doeth it. [Matthew 8:9]

This authority of position is the kind the old Montenegrin proverb refers to: “The best test of a man is authority.”

Plutarch elaborates:

There is no stronger test of a man’s real character than power and authority, exciting, as they do, every passion, and discovering every latent vice.

Shakespeare sounds the warning:

Man, proud man

Drest in a little brief authority, . . .

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven

As make the angels weep.

[Measure for Measure, act 2, sc. 2, line 117]

And the scriptures—ah, you know where we would turn, don’t you, because they give us the wisest and strongest and most sobering counsel concerning this manner of authority and those who bear it in the Church, in the home, and, I believe, with application everywhere else.

Behold, there are many called, but few are chosen. And why are they not chosen?

Because their hearts are set so much upon the things of this world, and aspire to the honors of men, that they do not learn this one lesson—

That the rights of the priesthood are inseparably connected with the powers of heaven, and that the powers of heaven cannot be controlled nor handled only upon the principles of righteousness. [D&C 121:34–36]

And then the choice pursuant verse:

That they may be conferred upon us, it is true; but when we undertake to cover our sins, or to gratify our pride, our vain ambition, or to exercise control or dominion or compulsion upon the souls of the children of men, in any degree of unrighteousness, behold, the heavens withdraw themselves; the Spirit of the Lord is grieved; and when it is withdrawn, Amen to the priesthood or the authority of that man. [D&C 121:37]

And then this verse that applies to all of us, and certainly there are none of authority in the kingdom who are not meant as its subject:

We have learned by sad experience that it is the nature and disposition of almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion.

Hence many are called, but few are chosen.

No power or influence can or ought to be maintained by virtue of the priesthood, only by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned;

By kindness, and pure knowledge, which shall greatly enlarge the soul without hypocrisy, and without guile—

Reproving betimes with sharpness, when moved upon by the Holy Ghost; and then showing forth afterwards an increase of love toward him whom thou has reproved, lest he [or she] esteem thee to be his enemy. [D&C 121:39–43]

Do you know the last in that series of beautiful verses?

That he may know that thy faithfulness is stronger than the cords of death. [D&C 121:44]

So this kind of authority is the one the prophet, the poet, and the philosopher warn against in terms of its misuse. I leave that as a lesson in itself, which you didn’t really need to hear, and move on to suggest some other kinds of authority, some varieties more effective and powerful than “You do it because I said so” or “It is so because I say so; I am in charge here.” There are diversities of authority more powerful than that. I name three.

The authority of personality, centering in one’s view of life, of oneself, of one’s fellowmen, or God, of eternity.

There is the authority of competence, the demonstrated capacity to do what the one in authority is commissioned to lead and help others do.

And there is the authority of integrity of character. [The categories of authority discussed in this talk have been variously expressed by different authors and speakers, including George Luce of the Bluebird Body Company in a talk to his employees. The content is the author’s own.]

Authority of Personality

The authority of personality is expressed not through position or power or command but in one’s view of life’s meaning and the worth of those who live it alongside us.

One who truly values other human beings and their potential and their uniqueness and their individual importance will lead by an authority that invokes respect because it radiates genuine respect. This kind of authority will be no less stable or even necessarily less demanding, and it will be infinitely more effective because it will inspire confidence and elicit respect and motivate commitment to accomplish the assigned task. It will preserve the dignity of people even when the leader must do something that hurts. It has to do with being human, being humane. It has to do with feelings and spirit.

I have in mind the electric declaration of a nineteen-year-old woman to a large, primarily adult congregation: “I am valuable!” she said through her sobs. She was a rebellious survivor of seventeen foster homes, she said, without anyone ever bringing her to believe she was important or valuable or that what she did meant anything to anybody. But in her present home, a loving, quiet couple had introduced her to the Savior through lives that really reflected his love and his compassion and his patience. They had taught her of him and the purposes and consequences of his sacrifice, and she had taken it personally, finally, and believed it. She said nobody had ever tried to help her to know that; perhaps she had not listened. But now life was totally different. “I am valuable!” she said. She knew about the price that was paid and believed it. Now life was totally different.

As a child I became acquainted with Goethe’s simple, profound invitation to all of us:

If you treat an individual as he is, he will remain as he is; but if you treat him as if he were what he ought to be and could be, he will become what he ought to be and could be.

Our perceptions are of great importance. If I perceive others to be intelligent, loyal, and trustworthy, and they know it, they will generally seek to justify that perception. They may openly seek to be all those things, or be all those things without our perceiving it, but they will be supported and sustained and very likely successful in their desires if we, perceiving these good things about them, let them know we do.

There are a lot of brilliant people in positions of authority who are ineffective leaders. Why? Today I picked up a civic bulletin and read these sentences:

Because they never get around to understanding and appreciating the feelings of the other people who are sharing this world with them, . . . sometimes, usually later in life, these egocentric individuals suffer painful hardships. They understand, then, often for the first time, the kind of problems less talented or less fortunate people have suffered all their lives. They suddenly discovered a new and important dimension: sensitivity to the feelings, emotions, and experiences of other people. [John Luther, quoted in The Rotary Bee 9, no. 7 (16 August 1988), 3.]

I have nurtured for nearly a lifetime the story of Martin Luther’s boyhood teacher who refused to wear the then-usual pedagogic bonnet as he taught his class. He would wear the robe but would not wear the hat. Why not? Why because, he said, “I do not know but that there sits among them one who will change the destiny of mankind. I take off my hat in deference to what they may become” (quoted in Marion D. Hanks, The Gift of Self [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1974], 126). And it happened that a lad named Martin Luther was sitting there when he spoke.

One of our missionary associates in England twenty-five years ago recently sent me a copy of a talk he had given in church. In it was a single sentence spoken to him personally by David O. McKay in Wales when that great, saintly man visited his mother’s ancestral home. He was apparently touched by an act of courtesy from this fine young missionary. President McKay said to him, “Son, once a gentleman, always a gentleman.” H. Perry Driggs has treasured that thought for half his lifetime, and I am sure he has tried to measure up to the invitation. He succeeds.

In the authority of personality we speak not of charisma or charm but of character, the expression of character, and the way one treats others. We speak of compassion and concern, of patience and pride and accomplishment.

Authority of Competence

And what of competence as a base for authority? If those coming under the influence of authority figures—and I remind you, every one of us may fill that designation for some others—if we can do so with admiration for the competence and capacity of the leader, then learning and following become acceptable, right—even easy—without the resistance of rebellion.

The authority of personal competence announces, without pomposity and beyond language, “I know what I am talking about. I am doing something I know about. I speak not by authority but with the authority of involvement and acquirement and experience. If you are willing, I can help you learn to do it. I admire you when you do it well because I am able to appreciate the strength of your performance and the difficulty of the preparation. I can also appreciate how it is not to know how to do it, and I will be patient and respectful as you develop your capacity in the undertaking.”

I went once as a frightened new hiree to a Boy Scout summer camp. Royal Stone was its director. A few of you will remember the man, a great man. He came to BYU and worked with boys and the teachers of boys for a time. Royal was a kind of remote figure in the camp, though he soon made it otherwise; but I became quickly attached to, as my mentor and leader, a man named Don Carlos Kimball. Surely someone here would have heard of him or know him. Lank and lean, a professional Scout executive, he was spending his summer there. He helped us learn how to be leaders. And the lesson I remember best is that he, beginning one morning with an adze and an ax and a tree, carved out—from sunup past sundown, without stopping—a two-bladed canoe paddle and then knelt in a canoe with that paddle and beat the old motor boat across the lake.

I saw all of that in one day. He took his adze and his ax, and out of available materials he created an instrument and used it, and I will never forget him.

During an early period in my college life I worked two jobs to meet needs at home and to keep alive my dreams of a mission. One of those jobs was at a repair shop for vacuum machines. We worked on motors and chassis and parts and then prettied them up and sent them home. One model then in vogue had a black Bakelite top, a heavy plastic cover, for the motor. It was breakable.

During my first hour on the job, the manager of the shop came out from his office in his business suit to reinforce the instruction I had just had from a senior benchman. M. K. Bradford, who is still living, took off his jacket, turned on the powerful buffing wheel, put some compound on it, grasped this black Bakelite top strongly in his big hands, and buffed it into shiny beauty without a word. Then he cautioned me for a moment about catching an edge, a sharp edge, on the wheel, explaining that the wheel was very powerful and that I should wear protective goggles and be cautious.

He went back to his office. I turned to the wheel, applied the compound, forgot the glasses, grasped an unpolished top strongly in my then-athletic hands, and put it to the wheel. The wheel accepted it quickly, tore it from my too tenuous grasp, turned it into a flying mass of tiny sharp parts, and spit it back in my face. I went to the sink, washed the blood away from many small cuts, checked my eyesight, clenched my teeth, and headed back for the wheel.

M. K. Bradford came from his office, checked my wounds to assure himself there was no serious damage, gave me no comfort—in fact, said nothing—took off his jacket, put compound on the wheel, picked up another unpolished Bakelite top, grasped it strongly in his big hands, and burnished the top to shiny brilliance. He then picked up his coat and walked back into his office. He said not a word, then or ever. I went back and began to buff tops and do the work. In the many months I worked at that shop before my mission, I did not lose another Bakelite top.

The great teacher Howard R. Driggs was asked by an admiring grandson how he in his early nineties retained in his mind and could quote almost endlessly the words of philosophers and poets and prophets. “Well, I had to pay the price of long consistent labor to acquire and memorize the knowledge,” he said, “and then I gave it and I gave it and I gave it until it was mine.”

Thus, the authority of competence.

Authority of Integrity

And then there is the authority of integrity. This announces to others that this person of authority is honest, that he is fair, that he understands, that he is modest, that he doesn’t pretend perfection, that he cares. They can count on him to listen and consider and to act with undeviating decency and appropriate example. He will act with authenticity, with wholeness, being at one with himself, with others, and with God. He is not petty, self-centered, judgmental, anxious to put down; he is a man of integrity.

As I think through the stories of many examples of integrity, I desire to share one only, and it is an example that almost capsulizes all that the good minds among you could supply of example and quotation.

Moroni was in the field. He was facing armies of enemies, and for a time, because of Helaman and his success, he thought they were winning the battle—but things changed. They didn’t get any logistical support; no troops were sent, no food. They began to lose, and, indeed, they were losing severely when Moroni sent an epistle to Pahoran, the governor of the land, calling him to task. He “was angry with the government,” says this fifty-ninth chapter of the book of Alma, “because of their indifference concerning the freedom of their country” (Alma 59:13).

He wrote again to Pahoran and to those working with him who had been chosen by the people to govern, and in the most intemperate of language he threatened that if they didn’t do what they were under obligation to do—that is, support these armies in the field—he and his armies would leave the enemy and come home and clean up the inner vessel, the inward leadership.

The language is interesting. They were being slaughtered, he said. He accused the governor of “thoughtless stupor,” saying:

Your brethren . . . have fought and bled out their lives because of their great desires which they had for the welfare of this people; yea, and this they have done when they were about to perish with hunger, because of your exceedingly great neglect. [Alma 60:7, 9]

He worked up a great anger:

Could ye suppose that ye could sit upon your thrones, and because of the exceeding goodness of God ye could do nothing and he would deliver you? Behold, if ye have supposed this ye have supposed in vain. [Alma 60:11]

And then he said it, “We know not but what ye are also traitors to your country” (Alma 60:18), and warned them that he was going to come back and clean the inward vessel if they didn’t begin to perform:

Except ye do administer unto our relief, behold, I come unto you, even in the land of Zarahemla, and smite you with the sword, insomuch that ye can have no more power to impede the progress of this people in the cause of our freedom. [Alma 60:30]

And then he attributed to inspiration his criticisms of Pahoran and his associates. In the next chapter, Alma 61, he received Pahoran’s answer. We don’t know very much about Pahoran (though quite a bit about Moroni).

Pahoran responded:

Behold, I say unto you, Moroni, that I do not joy in your great afflictions, yea, it grieves my soul.

But behold, there are those who do joy in your afflictions, yea, insomuch that they have risen up in rebellion against me, and also those of my people who are freemen. [Alma 61:2–3]

He told them that they had to flee, he and his associates, “to the land of Gideon, with as many men as it were possible that I could get. And behold, I have sent a proclamation throughout this part of the land” (Alma 61:5–6), trying to gather an army to come to your support. But we haven’t been able to do what we wanted to do because we ourselves have been forced to flee.

He continued: “They have got possession of the land, or the city, of Zarahemla; they have appointed a king,” and so forth (Alma 61:8).

And then in what to me is a verse I have wept over many times because it reflects, I suppose, the nature of my own limitations, Pahoran somehow, somehow, managed to meet this accusation, this question about his patriotism, even the suggestion that Moroni was inspired to believe that they were traitors. This is how Pahoran answered:

And now, in your epistle you have censured me, but it mattereth not; I am not angry, but do rejoice in the greatness of your heart. I, Pahoran, do not seek for power, save only to retain my judgment-seat that I may preserve the rights and the liberty of my people. My soul standeth fast in that liberty in the which God hath made us free. [Alma 61:9]

And then he defended quietly and modestly what they had tried to do and told what they would do. He invited Moroni to return and they would form an army and engage the enemy.

“In your epistle you have censured me, but it mattereth not; I am not angry, but do rejoice in the greatness of your heart.”

I read what Peter, who had learned to know the Lord, said of him “who, when he was reviled, reviled not” (1 Peter 2:23). Peter left judgment in the hands of one who is just.

Christ [left] us an example, that [we] should follow his steps:

Who did no sin, neither was guile found in his mouth:

Who, when he was reviled, reviled not again; when he suffered, he threatened not; but committed himself to him that judgeth righteously:

Who his own self bare our sins in his own body on the tree, that we, being dead to sins, should live unto righteousness: by whose stripes [we] were healed. [1 Peter 2:21–24]

One in a position of authority may endure his day in power without these other mentioned elements of authority, I suppose. One who has the position and the power may live it out, and he may—he may—absent these other elements and qualities, as did Jehoram, ancient king of Judah, a young man who reigned in Jerusalem eight years without concern for others, without competence, without integrity, who “departed without being desired” (2 Chronicles 21:20).

There are several other things I would like to say, and I will undertake for a few moments to add an illustration or two.

When we talked earlier of in loco parentis, the school assuming some of the burdens and blessings of parenthood, caring about what kind of people young people are, there came to my mind the day when, representing the educational system of the Church, I went to the University of Missouri as a trustee and sat with others across the land who were in a conference. The theme of the conference really was the abandonment of the notion that universities have anything like the relationship of in loco parentis with their students.

I never want to forget the anxiety and fervor expressed by the young student president who came to greet a group of these regents, listened to the latter part of a speech keynoting the demise of in loco parentis, and then came with obvious distress to the podium, where he quickly filled the role of welcoming us and said some words that I, at least, have not forgotten:

If, in fact, you, representing the universities of the land, reject the responsibility to act for us in the role of parents who care about us, then you are entitled to know that that leaves a whole lot of us without any parents at all.

We are dealing, you and I, whatever our position or experience or function is on this campus, as authority figures to young people.

Sister Hanks was helping me recall a phrase from years ago when I spoke to a national group about young people and said of them that we habitually underestimate their intelligence and overestimate their experience. They are bright, most of them, and very able, but they have had little experience. From Shel Silverstein—you young mothers and fathers should know him—let me read a few lines:

God says to me with a kind of a smile,

“Hey how would you like to be God awhile

And steer the world?”

“Okay,” says I, “I’ll give it a try.

Where do I set?

How much do I get?

What time is lunch?

When can I quit?”

“Gimme back that wheel,” says God,

“I don’t think you’re quite ready yet.”\

[“God’s Wheel,” in A Light in the Attic (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1981), 152]

They are not quite ready yet.

If you have a heart for sentiment, listen:

When we plant a rose seed in the earth, we notice that it is small, but we do not criticize it as “rootless and stemless.” We treat it as a seed, giving it the water and nourishment required of a seed. When it first shoots up out of the earth, we don’t condemn it as immature and underdeveloped; nor do we criticize the buds for not being open when they appear. We stand in wonder at the process taking place and give the plant the care it needs at each stage of its development. The rose is a rose from the time it is a seed to the time it dies. Within it, at all times, it contains its whole potential. It seems to be constantly in the process of change; yet at each state, at each moment, it is perfectly all right as it is. [W. Timothy Gallwey, The Inner Game of Tennis (New York: Random House, 1974), 37]

Finally, let me share with you that as a lad I was strangely moved, among the books I was reading, by one book and one incident. The incident and the book were later made into a prominent movie. The book was The Keys of the Kingdom by A. J. Cronin, a physician and novelist. In it is the incident of a young priest who was assigned to work with an old, worn, unappreciated parish priest who had given his life to Christ, who had served with great unselfishness but was not responded to or encouraged by his hierarchical superiors. The young priest, brilliant, vigorous, talented, saw this and decided to surrender his vocation. He would not be a priest if this is what happened to those who unselfishly and truly served. The older priest urged against his abandoning his calling with these quiet words of encouragement:

You’ve got inquisitiveness and tenderness. You’re sensible of the distinction between thinking and doubting. . . . And quite the nicest thing about you, my dear boy, is this—you haven’t got that bumptious security which springs from dogma rather than from faith.

[A. J. Cronin, The Keys of the Kingdom (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1941), 144]

I would fondly wish, though I honestly do not anticipate, that no teacher or worker will remain at BYU, and no student ever depart, filled with “that bumptious security that springs from dogma rather than from faith,” who does not have and is determined to stifle in others “inquisitiveness and tenderness,” who is not “sensible of the distinction between thinking and doubting.”

I bear witness that there is no other function more important in my judgment than to be able to influence, in his or her inner self, in that part susceptible to nobility and decency, that part which in us is better than we know, the great young people who come along in this coarsening world, wondering. We have so many who are so good, and I marvel that they manage it.

I commend you and congratulate you on your election and selection to serve here. I think you are highly honored, and I really don’t care—and perhaps you know that I really mean that—whether you are the plumber fixing a fountain or a gardener planting a garden or the president in his office. We are authority figures, and our outreach, or our interest—or our lack of it—may influence these of little experience but great capacity to learn.

God bless you and sustain you and strengthen you and help you to be, as Brigham Young once encouraged others to be, gentle with opposite or other viewpoints. He spoke of those who would measure their associates by their own length of bedstead and cut them off if they differed in thought or feeling. Be gracious, he said, for the whole world is before us. (See Journal of Discourses [London: Latter-Day Saints’ Book Depot, 1855–1886] 8:9.) Don’t demean the message or the God who gave it by minimal comprehension. If your view is small, be modest and seek to learn.

Generally speaking, I cannot believe there is a faculty or a staff or an administration superior to those at this school, and I have to say that I love it and believe in it and would do anything I could in this world to promote for his marvelous contributions this great young man who leads the school; and those who labor with him are of equal merit. May the Lord bless you, I pray in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

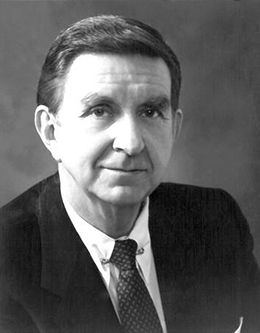

Marion D. Hanks was a member of the Presidency of the First Quorum of the Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this BYU annual university conference address was given on 23 August 1988.