Vanity it is, I add, and foolishness indeed, to pretend—to say and not to do, to seem and not to be.

This is always a pleasant sight and a special experience. I visited the missionaries last week in the Missionary Training Center and told them the story of a person who was imposed upon by a bully after a traffic accident. When the police found the victim he was in pretty rough condition.

They asked him, “can you describe the man who hit you?”

He said, “That’s what I was doing when he hit me.”

Well, describing to others the situation in which I find myself now would be an unsuccessful endeavor. I shall not try to do it, but I do congratulate you on the special privilege you have of being here, and I am quite anxious this morning that my visit—an opportunity I always treasure—may be useful to you and to me. I am particularly prayerful that I may be directed among the many thoughts that have crossed my mind to those that may be particularly important to you. I do not have a manuscript but do have some notes. One of the notes reminds me of something on a tombstone in England—it really is—that may be interesting to you. It consists of a single line that reads, “I told you I was sick.” We do not always listen wisely or well.

I remember also, for some reason, a long-forgotten account of a man who wanted to go hunting on property that had theretofore been posted against it. So he talked with the owner of the property who granted permission on one condition—that the prospective hunter do him a favor and shoot his mule. It was in a very sad condition, and really needed to be dispatched, but the owner had such a long and loving relationship that he did not want to do it himself. So he said, “If you’ll just shoot my mule for me, then you may hunt here.”

The petitioner went back to his group and, thinking to have a little fun, said, “The man won’t let us hunt here today. That makes me very angry after we have come so far and I intend to do something about it. You wait here. I am going to get even with him.” So he crept up to the mule and , upon reaching it, shot it.

Just after he did, he heard two shots from behind him. “What are you doing?” he shouted at his two companions, who had also crept up behind him. They answered, “We got his horse and his cow; let’s go!”

That leads me into my central idea, which I suspect you will remember not because I say it but because it is so very important.

In the twenty-third chapter of the book of Matthew are some lines to which I would invite you to listen carefully as I establish a theme for these few moments.

Then spake Jesus to the multitude, and to his disciples,

The scribes and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat:

All therefore whatsoever they bid you observe, that observe and do; but do not ye after their works: for they say, and do not.

For [he is going to give some examples] they bind heavy burdens and grievous to be borne, and lay them on men’s shoulders; but they themselves will not move them with one of the fingers.

But all their work they do for to be seen of men: they make broad their phylacteries, and enlarge the borders of their garments.

And love the uppermost rooms at feast, and the chief seats in the synagogues,

And greetings in the markets, and to be called of men, Rabbi, Rabbi. . . .

[Then he counsels that no one is to be called master save He.] But he that is greatest among you shall be your servant.

And whosoever shall exalt himself shall be abased; and he that shall humble himself shall be exalted.

But woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For ye shut up the kingdom of heaven against men: for ye neither go in yourselves, neither suffer ye them that are entering to go in.

Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye compass sea and land to make one proselyte, and when he is made, ye make him twofold more the child of hell than yourselves. . . .

Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For ye pay tithe of mint and anise, and cumin, and have omitted the weightier matters of the law, judgment, mercy and faith: these ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone.

Ye blind guides, which strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel.

Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye make clean the outside of the cup and of the platter, but within they are full of extortion and excess.

Thou blind Pharisee, cleanse first that which is within the cup and platter, that the outside of them may be clean also.

[Finally,] Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye are like unto whited sepulchers, which indeed appear beautiful outward, but are within full of dead men’s bones, and of all uncleanness.

Even so ye also outwardly appear righteous unto men, but within ye are full of hypocrisy and iniquity. [Matthew 23:1–7, 11–15, 23–28]

That terrible indictment to the Pharisees came because they were addicted to the policy and program of seeming instead of being. It is said that one of the magnificent leaders in ancient times did what he did with such grace and graciousness and goodness because he had early adopted a motto—a guiding principle—which was inscribed inside his shield. Only he, but repeatedly he, saw it in the midst of his deeds of bravery, courage, and kindness. Inscribed there were these words: “To be and not to seem.”

The Pharisees, fastidious and meticulous in their adherence to the letter of the law, were seemers. “Pretense,” “say and do not”—these were the words the Lord used to describe them; and repeatedly He used that terrible word which makes all of us cringe—“hypocrite.” Many who have understood what the Lord meant have given us additional counsel in consequence of what He said; and of them all, I choose one that has been of special meaning to me for many years. Thomas å Kempis was born nearly six hundred years ago. He wrote these words, to which I invite you to listen carefully in context of our theme:

The doctrine of Christ exceedeth all the doctrines of holy men; and he that hath the Spirit, will find therein an hidden manna.

But it falleth out, that man y who often hear the Gospel of Christ, are yet but little affected, because they are void of the Spirit of Christ.

But whosoever would fully and feelingly understand the words of Christ, must endeavour to conform his life wholly to the life of Christ.

What will it avail thee to dispute profoundly of the Trinity, if thou be void of humility, and art thereby displeasing to the Trinity?

Surely high words do not make a man holy and just; but a virtuous life maketh him dear to God.

I had rather feel compunction, than understand the definition thereof.

If thou didst know the whole Bible by heart, and the sayings of all the philosophers, what would all that profit thee without the love of God and without grace?

[I think that I shall read part of this next paragraph also, still from Thomas å Kempis.]

Vanity therefore is to seek after perishing riches, and to trust in them.

It is also vanity to hunt after honours, and to climb to high degree.

It is vanity to follow the desires of the flesh, and to labour for that which thou must afterwards suffer grievous punishment.

Vanity it is, to wish to live long, and to be careless to live well. [Thomas å Kempis, Of the Imitation of Christ, chapter 1]

Vanity it is, I add, and foolishness indeed, to pretend—to say and not to do, to seem and not to be.

In its worst form, that is hypocrisy. In its best form, I suppose, it might be thought to be pursuing the “as if” principle—that is, to say to oneself, “I will behave as if I were honest, decent, moral, courteous, gracious, sensitive, and courageous; and in so behaving, I will acquire the capacities, make the habits, and become capable of being all those things.”

I suspect that most of us fall some place in between. We do not savor, and in fact sicken at, the thought that we are hypocrites, and yet we do so much to be seen of men. We sometimes say that which will tickle the ears of men. We pretend, knowing that in our own quiet places—our closets or, wherever the place, our minds—we are not what we seem.

That is not to suggest that only the perfect may act with credibility in matters of important principles. All of us fall short and are inevitably visited with the pangs and pains of our own failures; there is a universal understanding of that, since none of us is exempt from it. But to deliberately pretend, to put on a show, to give long prayers when we have devoured the widow’s house, to do less than we can and should and pretend to do, to go through motions—not because they are honest efforts to do better, but simply to try falsely to fit somebody’s conception of what we are—all of this is vanity and foolishness indeed. Christ’s life, His instruction, and His testimony centered in being what we ought to be. And there is great room in His holy heart to forgive when we fall short in genuinely trying to be what we ought to be.

Early this morning, under the heading “be and not seem,” I noted for myself an idea or two about Him, and I share them with you. These thoughts are not a pretense at comprehensive scholarship but simply an expression of what in Him seems to me at this hour to be so admirable and beautiful and worthy of emulation. I noted first His acute awareness and sensitivity to the lives and needs of others, to the point that the woman in the mob who touched the hem of His garment found response, not only in her own well-being but in His knowledge of the incident. He knew He had been touched, though ever so lightly. And when He mentioned it, His disciples, seeing the thronging multitudes, wondered how He could ask such a question. Who had touched Him? Many were touching Him. But one touched Him with a special need and a heart ready for the response, and He knew it. (See Mark 5:25–34; Luke 8:43–48.)

Another characteristic of the Lord was His acceptance of others as they were without the intention to leave them as they were. He could heal the body, bless the mind, and help change the soul of one who was willing—the prodigal, Zaccheus, Magdalene. Remember also that moment on the cross when He forgave. Most of all, I am touched by that tender time when a father who loved his ailing son, and who had sought help from the disciples and had not received it, presented himself to the Lord pleading for help. To him the Lord said, “If thou canst believe, all things are possible to him that believeth.” Do you think that one who has not loved a son might have a little less sensitivity to this. But with his heart and his life hanging on his son’s well-being, when he was asked if he had faith he answered, “Lord, I believe; help thou mine unbelief.” He did not have perfect faith, but he knew to whom he spoke and trusted in Him. (See Mark 9:17–27.) Oh, how I love and need that!

The Lord’s courage—while it was not political, not always persuasive, and did not, in terms of this life and the immediacy of the Cross, prevail—was clean, strong, noble, and godly. He spoke the truth and He acted in conformity with it. He also had great humility. He made full use of His power to serve, heal, help, and teach, always making it clear that He relied on His Father and the Spirit. He did it all in the spirit of “the least among us,” knowing always who He was and what powers He might have invoked.

We should not have favorite stories at the expense of many others that another time, another day, more prayers, more tears, and more living may make favorites; but over many years I have loved this one.

He spake this parable unto certain which trusted in themselves that they were righteous, and despised others;

Two men went up into the temple to pray; the one a Pharisee and the other a publican.

The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, God, I thank thee that I am not as other men are, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even as this publican.

I fast twice in the week, I give tithes of all that I possess.

And the publican, standing afar off, would not lift up so much as his eyes unto heaven, but smote upon his breast, saying, God be merciful to me, a sinner.

I tell you, this man went down to his house justified rather than the other: for every one that exalteth himself shall be abased; and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted. [Luke 18:9–14]

Finally, Christ possessed the love that was greater than faith and greater than hope, that never faileth, that expresses itself in service, in sacrifice, in giving—the love that opened to mankind the door to all that is good here and all that is creative, progressive, challenging, exciting, satisfying, and sweet hereafter. This love was not just language or example but was also specific instruction. In what to me may have been the high point of His instruction about love, He said—and you know the exact words that I could quote, but let me paraphrase—there are those who are hungry and thirsty, who lack sufficient clothing, who are strangers or feel as such, who are sick, who are in prison. Love means doing something for them. “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me” (Matt. 25:40). This is not a catalog of His virtues, but a testimony of His great heart.

We who do not want merely to seem but would really like to be will find that the path He laid out in His instruction, in His example, in His testimony—in His life—is one not beyond our capacity to follow. There are those who need to touch us and feel a response of acceptance, affection, and mercy. There are those who are hungry—hungry for food; and we have a little, though perhaps not much. There are many among us who still feel strange in this great institution and who need to be brought in. There are people in hospitals and prisons who are not beyond our capacity to reach.

I shall give you an example or two as I try to make this meaningful; and I risk a little because one of the examples is the latest and sweetest and loveliest of my own blessings and in sharing I shall spoil it in a sense.

First let me share with you what I experienced overseas as I listened to a modest, gentle, manly father wearing the uniform of his country, leading and doing a job of importance while he gave great service to the Kingdom and his fellowmen. He told me of his work among many other officers in the prosecution arm of the United States Army—men who were not like him, who were not living the kind of life he was living. They had not been very much interested in the fact that he was a Mormon leader, or that he had a strong sense of loyalty to his wife and children and to God, or that he had control of his tongue and a way of speaking different from their own. None of that impressed them very much. He and his wife found themselves leaving required social events early quite frequently because the activities of the evening were not wholesome. As such an evening would progress, other guests occasionally became ugly as they imbibed additional spirits, lost their normal restraints, and sometimes acted less like men and women than like animals. He was not one to judge lightly or readily, and he was not expressing harsh judgments against them; he was simply presenting a setting for an incident that I shall not forget.

He said that they went to a Christmas party, more happily this time because the host family was a fine family who had little children of the same general age as their own. The children came in their pajamas by invitation and, joining the host family children, played together in another room while the adults ate their dinner. Periodically the children came out and interrupted proceedings with childish playing or questioning until finally the Mormon father, his sense of humor tried a little bit, said, “Now, look—you kids go on in the other room and stay there and don’t come out again or else.”

They sat at dinner in peace for a time; then the bedroom door opened and a little line of children filed out, the two-year-old in the vanguard. (They were sure daddy would not do too much violence to him.) The older brother had him by the shoulders and was egging him on. As the father, disturbed and feeling that he had to do something because he had said he would, began to push back his chair, the two-year-old said, “Daddy, you and mama forgot family prayer.”

Instead of expressing embarrassment, the mother said, “Honey, we did forget.” She pushed her chair back, he rose from his, and they excused themselves and quietly took their children and the other children into the bedroom where they performed this simple act of family unity and faith. Then they quietly came back to the table, seated themselves, and went on with the dinner.

“It was a different night,” he said to me, “and it’s been a different office. That party didn’t end like all the rest. And at the office things are different now.”

To be and not to seem brings great blessings.

To conclude, here is my own recent experience. There sits a man on this stand today who I admire very much. He has a brother who is a physician and a medical researcher. I had the great honor to visit that brother and his family and others in a stake presidency in another place. The visit was beautiful and sweet, but not extraordinary. We met the families—the wives and children—and conversed with them, got to know and love them, and left the stake feeling like brothers to these choice people.

After some months had passed, I met the physician on the street in Salt Lake City and we talked for a little while. He seemed pleased that I would remember him, and I got the feeling that there was something he would like to have told me; but both of us had to hurry and so we just put our arms around each other and parted. A few days later a letter came. I shall read it to you just as it is written. If I had any inkling that you would misunderstand it or the purpose I have in reading it, I would not share it. I plead with you, let your hearts tune in for just a moment.

Dear Brother Hanks:

Meeting you on the street the other afternoon was a very pleasant surprise for me, and I’m sorry we were in such a hurry because I wanted to share an experience with you that’s been very dear to me. Thus, I thought I’d take the opportunity to write you this note and tell you. Perhaps you remember when you visited our stake, the lunch was served by my wife and my young daughter. You asked my daughter her name and she replied, “Mary.” You told her that that was the most beautiful name for many reasons. You told her that you also had a daughter named Mary and told her about your Mary. That episode changed Mary’s attitude about her name. Up to that point, she had not liked her name very well because she thought it so plain. Thereafter, she thought of her name in a different light. I don’t know exactly what you told her or what message she received from you, but I must tell you that it changed her life. My wife and I have reflected on that experience a great deal during these past few months and it has brought back such pleasant and very choice memories. We will be forever grateful to you for that brief encounter and for what it did for Mary. I’m sure that you had no way of knowing that Mary passed away a short time after that. Her death was very sudden and due to medical reasons that are not yet explained. I wanted you to know how you touched her life and thank you for it.

Can we really believe that we have nothing to give? That we are so weak and so simple, you and I? That our consciousness of our personal failings and inadequacies disqualifies us from helping others? That we really cannot expect anybody to care very much or respond to us? Oh, God help us to be and not to seem—to give, to love, to be humble. If we cannot lift up even our eyes unto heaven, then God help us to have sense enough to cry, “God be merciful to me, a sinner.” But you have so much to give. Let this simple incident say what I could not say if I had tried for an hour, and tell you that I know this is God’s work and that we are really neighbors, brothers, sisters—His children. There is in the least of us—even in the most dependent—that which is better than we understand; shared, it can bring more than we know to those who seek. In the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

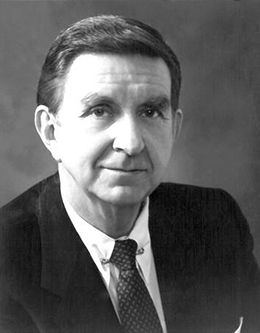

Marion D. Hanks was a president of the First Quorum of the Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 23 January 1979.