Music is a language that speaks to everyone. Its healing power is expressed by people in every country in the world. Whether we listen to music in church, at home, or in the concert hall, we do it to feel better about our circumstances.

Thank you so much. I would like to start by thanking several very special people that I have been blessed to come to know at Brigham Young University. First, my deepest gratitude to university president Kevin J Worthen and academic vice president C. Shane Reese, whom I first met last year. I would also like to thank my friend Dr. John R. Rosenberg, whom I first met in 2014 while visiting BYU at the invitation of my good friend and professor of English, Dr. Gregory Clark. Greg has been a staunch supporter of jazz music and civic engagement throughout his career.

In 2020, it was my great honor and privilege to participate in a BYU forum assembly. As it turned out, because of the pandemic, the BYU forum was the last time that I was able to perform in public.

I am a musician—not a politician, TV personality, or medical expert. I play music for people, and I have taught others to play since I was twelve years old. It is who I am and what I do. This is the first time in almost fifty years that I didn’t know when I would be able to perform in public again. That led to a profound sense of loss, but it also gave me a renewed sense of purpose. While I have always valued the importance of mentoring, and I have trained and supported many aspiring young musicians over the years, last year presented us with a whole new range of challenges. We had to find innovative ways, using a variety of technologies, to perform for people virtually over Zoom and in other settings.

I have been thinking a lot lately about where we are as a country. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought out the best, and the worst, in people in America. For many, if not most of us, this past year has been a time of isolation, and we humans are not meant to live in isolation. I lost my sight when I was five years old. I remember very little of that time, but I do remember the initial deep sense of loneliness and isolation that I went through then. Over time, I have come to realize how much physical sight has to do with our disconnection from each other.

Sight allows us, at a glance, to see the differences in people and judge and categorize them in a negative way. Often when we see a person who does not look like us, we focus on those differences: different color skin, different facial features, or obvious differences in status, wealth, or social background. As a result, we don’t ever get to know them or value their life struggles. We can’t feel their pain, share their joy, or identify with their families and friends. We can’t really understand the reasons for the decisions that they have had to make in their lives. When we fail to see each person as a unique individual, but instead see them only as someone who is Black or White or Asian or disabled or poor—whatever it is, we are disconnected from them because of the stereotypical labels that society often places upon them.

Unfortunately, we may have low expectations of people we don’t consider as being part of our peer group or social clique. But it doesn’t have to be that way, because there is a tie that binds us all. We need to take the time to really see each person, each individual human being—especially those who don’t look or act like us—because if we hold on to and build upon that little thread that binds us together, our ties will become stronger, and we will develop more of a sense of communion and trust with each other.

We are going through a very difficult time in America right now. Perhaps it is the pandemic that has tipped us over the edge, or maybe it has something to do with our current obsession with celebrities and social media. I do know that people are struggling every day. Struggling with whether they should visit their parents or grandparents. Struggling with whether to go to a job that they need to feed their families, even though they risk getting sick with COVID. Our country is struggling with racial intolerance, sexism, hatred, and chaos. How can we turn this bitterness into hope, optimism, and a society in which everyone has equal access to resources, education, and opportunity? We need to do this, because one thing I know for sure is that you can’t make it out here in the world by yourself.

I am a jazz musician, and, as the great Duke Ellington always said, “Problems are opportunities.” Art, therefore, is mainly concerned with proposing solutions to problems. That is why elegant form and logical structures are so essential in art, because without them, we have chaos. And chaos is easy to create and easy to succumb to, but it does not help a group of people survive through adversity.

Music is a language that speaks to everyone. Its healing power is expressed by people in every country in the world. Whether we listen to music in church, at home, or in the concert hall, we do it to feel better about our circumstances. My mother taught me that the essential quality that we musicians must have is the ability to enable people to feel something deep inside whenever we play for them. One thing I know for sure is that, for the rest of my days, I will share my musical gift to bring joy, peace, and inspiration to others.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

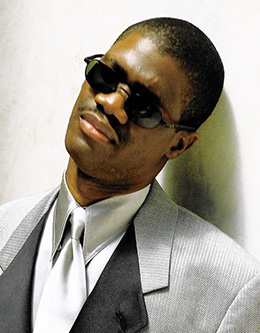

Marcus Roberts received an honorary doctorate when this BYU commencement address was given on April 22, 2021.