Among the words of the English language the word farewell is the hardest to pronounce, and I, probably, will succeed very poorly at my present attempt.

There are two periods in a man’s labors when circumstances seem to dictate to him the advisability of making as few words as possible: they are at the beginning and at the end of his work. At the former occasion he may outline his work and make promises for its faithful execution, but behold, conditions arise, altering the first entirely or preventing the fulfillment of the second. The latter period is at the close of his work, when in most cases it would be best to let the work speak for itself. In the last of these conditions I find myself on the present occasion, at which, after a period of many changing scenes of light and shade, I am about to surrender my office as the principal of this academy into other hands.

Although whatever I may say, therefore, can neither add to nor take from the work done during the past fifteen years and a half, nor would it be possible to refer to any facts of sufficient moment in the history of the institution that were not already known to this audience, nor could I delineate any of her characteristics with the hope of enhancing the estimate in which she is held among the people, there is a past—remindful of struggles and victories, of sorrows and joys, of small beginnings, and of astonishing developments—claiming recognition. There is a present—beaming with gratitude for past achievements, with joy for beautiful surroundings, and with pride in the general appreciation—giving us an object lesson. And there is a future—full of fond anticipations for continuous prosperity, of elements of increased usefulness, and of prophecies for the participation in Zion’s glory—enjoining upon us the duty of redoubled efforts.

All these considerations are grouped together in the kaleidoscope of the mind by the solemnity of the hour; and here I am in the faint endeavor to express in words the whole vision as reflected upon my soul.

When to the students at the beginning of the experimental term, April 24, 1876, the words of the Prophet Joseph Smith—that he taught his people correct principles and they governed themselves accordingly1—were given as the leading principle of discipline, and the words of President Brigham Young—that neither the alphabet nor the multiplication table was to be taught without the Spirit of God—were given as the mainspring of all teaching, the orientation for the course of the educational system inaugurated by the foundation of this academy was made, and any deviation from it would lead inevitably to disastrous results, and, therefore, the Brigham Young Academy has nailed her colors to the mast.

I had a dream, but, in the language of Byron, it “was not all a dream.”2 One night, shortly after the death of President Brigham Young, I found myself entering a spacious hallway with open doors leading into many rooms, and I saw President Brigham Young and a stranger, while ascending the stairs, beckoning me to follow them. Thus they led me into the upper story containing similar rooms and a large assembly hall, where I lost sight of my guides and awoke.

Deeply impressed with this dream, I drew up the plan of the localities shown to me and stowed it away without any apparent purpose for its keeping, nor any definite interpretation of its meaning, and it lay there almost forgotten for more than six years, when in January 1884 the old academy building was destroyed by fire. The want of new localities caused by that calamity brought into remembrance that paper, which, on being submitted suggestively to the board, was at once approved of, and our architect, a son of President Young, was instructed to put it into proper architectural shape.

However, another period of eight years had to pass, and the same month of January, consecrated in our hearts by the memory of that conflagration, had to come around eight times again ere we were privileged to witness the materialization of that dream, the fulfillment of that prophecy. When in future days people will ask for the name of the wise designer of the interior of this edifice, let the answer be: Brigham Young!

If it is true that in trying moments of great emergencies visions of the past are engrossing the mind with lightning rapidity, I do not wonder that just now the memory of those members of the board who have followed already their great leader behind the veil is assuming startling vividness. Thus I recall with a grateful heart the names of Sister Coray and of Bishops Bringhurst and Harrington, who, I doubt not, together with President Brigham Young, are witnessing from the realms of the unseen world the proceedings of this glorious day.

Ancient Rome engraved the names of her most distinguished senators on tablets of gold, but the Brigham Young Academy has more precious material to preserve the names of those faithful instructors who have labored in her hall until they were called away to other and more extensive fields. There will be written with imperishable letters of loving gratitude in the hearts of their pupils the names of Bishop John E. Booth; Doctors Milton H. Hardy, James E. Talmage, and J. Marion Tanner; Professor Willard Done; Brother A. L. Booth; Sisters Zina Y. Card, Tenie Taylor, and Laura Foote and others, among which galaxy of bright stars I hope to gain a humble place from today.

Among the words of the English language the word farewell is the hardest to pronounce, and I, probably, will succeed very poorly at my present attempt. So you will have to accept the will for the deed.

To President Smoot and the members of the Brigham Young Academy Board of Trustees, I try to say it in expressing to them my gratitude for having stood by me in days of good and evil report; to my dear fellow teachers I leave my blessings and take with me the consciousness of their love and friendship; and to the students I repeat the words of holy writ, saying, “Remember your teachers, who have taught you the word of God, whose end you should look upon, and follow their faith.”3

To you all I recommend my successor, Professor Benjamin Cluff; bestow upon him the same confidence, trust, and affection that you so lavishly have shown me, and the seed of such love will bring you a rich harvest.

And now a last word to thee, my dear beloved academy: I leave the chair to which the Prophet Brigham had called me, and in which the Prophets John and Wilford have sustained me, and resign it to my successor and maybe others after him, all of whom will be likely more efficient than I was—but forgive me this one pride of my heart that I may flatter myself in saying, “None can be more faithful.” God bless the Brigham Young Academy. Amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

Notes

1. See John Taylor, “The Organization of the Church,” Millennial Star 13, no. 22 (15 November 1851): 339.

2. Lord Byron, “Darkness,” in The Prisoner of Chillon and Other Poems (London: John Murray, 1816), 27.

3. See Hebrews 13:7.

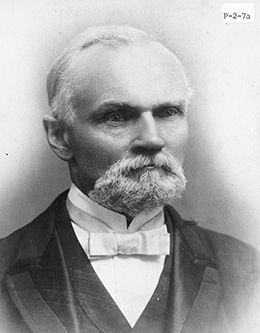

Karl G. Maeser was completing his time as principal of the Brigham Young Academy when he gave this address on 4 January 1892.