In American history this sublime and serious combination of religion and democracy has overall been a force for great good. Some of the most important movements of conscience in our history emerged from the convictions of religious people and used the language and liturgy of faith to build popular support.

Thank you so much, President Samuelson, for that introduction. And thank you all for that extremely warm welcome. It’s great to be here at this beautiful and storied Brigham Young University campus. I must say, President Samuelson, that in listening to your introduction, which was very generous, I thought back to an occasion a few years ago in Washington, DC, when former secretary of state Henry Kissinger was the keynote speaker.

The chairman of the meeting got up at the moment Kissinger was going to speak and said, “Henry Kissinger really needs no introduction, so I give you Dr. Henry Kissinger.”

Kissinger got up and said in his inimitable voice: “It’s probably true that I do not need an introduction, but you know it’s also true that I like a good introduction.”

President Samuelson, that was a great introduction from a great man who honored me with a comment that appears in the front of my book The Gift of Rest and who has done such an extraordinary job here at BYU. I have the greatest admiration for this university’s work in educating minds, ennobling spirits, and inspiring in its students a commitment—a real-life commitment—to the words etched in stone at the entrance of this great campus: “Enter to learn; go forth to serve.” I will come back to that.

Let me now personally thank Elder L. Tom Perry and Elder Quentin L. Cook of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles for being here this morning and for their leadership in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I am truly honored by their presence and very grateful for the opportunity we had to speak for a few moments before this forum began. It is the faith of the Church that has inspired, informed, and energized this great university and succeeding generations of its graduates.

An Ecumenical Spirit

The Spirit of God fills this campus, and with it I can tell you today that I feel an ecumenical spirit. I feel that ecumenical spirit so deeply that I’m going to venture forth and take the risk of telling a joke—an ecumenical joke. Perhaps some of you have heard it; if you haven’t, I hope you enjoy it.

This is the story of the day when the chief rabbi in Jerusalem called the pope in the Vatican and said, “Your Holiness, I have good news and bad news to tell you. Which would you like to hear first?”

The pope said to the chief rabbi, “I’d like to hear the good news first.”

So the rabbi said to the pope, “Well, here’s the good news: I can tell you for a certainty that the Savior is coming to earth tomorrow.” (Now we have a minor doctrinal dispute about whether this is the First or the Second Coming, but we’ll be able to handle that.)

So the pope said, “That is not just good news; that’s the greatest news. That’s the news we’ve all been waiting to hear. What possibly could be the bad news?”

“Well,” the chief rabbi said, “apparently He’s going to Salt Lake City.”

Thank you for laughing. I do feel a special connection to the Mormon faith and to BYU because of the core principles this university stands for, which are at once rooted in the tradition of the Mormon faith but also clearly shared by most Americans and, I would say, certainly most religiously observant Jewish Americans. Throughout my life I’ve been blessed to experience the bond that exists between people of faith whose faiths are different. And I have felt that in my life with the Mormons I have been privileged to know, to have as friends, or to work with. People of faith share a lot, beginning with our gratitude for what we’ve been given—first and foremost for our lives.

We believe both what the Bible and the Declaration of Independence tell us. The Bible clearly tells us we are not here by accident but because of a divine, godly act of creation. And as the declaration, written by men of faith, tells us, every one of us is a child of God, and, as such, each and every one of us has inalienable rights, by birth, to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” We believe that each of us, with those rights, also has responsibilities that are articulated in our faiths. And we believe that each of us has a destiny and that this great nation of ours has a destiny.

That’s why I’m so pleased that you have asked me to speak this morning about faith in the public square—faith in the American public square. It is a subject that I’ve thought about a lot, written about a little bit, and lived a lot in what I think is a classically and wonderfully American way. My Jewish faith is central to my life. I was raised in a religiously observant family. Given to me by my parents and formed by my rabbis, my faith has provided me with a foundation, an order, and a sense of purpose in my life. It has much to do with the way I strive to navigate in a constructive way through every day, both personally and professionally, in ways that are large and small.

The Sabbath Day

One of the central observances of my faith and also of the Mormon faith is the observance of the Sabbath: to “remember the sabbath day,” as the commandment says, “to keep it holy” (Exodus 20:8). As President Samuelson has been kind enough to say, my observance of the Sabbath is the subject of the book I’ve written called The Gift of Rest: Rediscovering the Beauty of the Sabbath.

Some people have asked, “Why would a United States senator write a book about a religious subject like the Sabbath?”

It’s a good question. This book is very different from anything I’ve ever written. I think that while people in Connecticut certainly know I’m Sabbath observant—and perhaps people around the country, because of my vice-presidential campaign in 2000, also know that I’m Sabbath observant—I never really was asked to talk a lot more than that about it. I think people probably know what I don’t do from Friday night sundown to Saturday night sundown—which is I don’t work unless there’s an emergency of some kind—but they don’t know what I do. So I decided to write this book to try to share what I call the gift of Sabbath rest.

It is interesting that the Sabbath is observed by all of us as the result of a commandment in the Bible that God gave to Moses. Though it started as a directive, I know that many of you who observe the Sabbath, as my family and I do, now experience it as a gift. In the Talmud a rabbi of centuries and centuries ago imagined a conversation between God and Moses in which God said, “Moses, in my storehouse I have a very special gift for you. It is called the Sabbath” (paraphrased from New Edition of the Babylonian Talmud, ed. Michael L. Rodkinson, vol. 1, Tract Sabbath [New York: New Amsterdam Book Company, 1896], 18).

I decided to write this book because I think Sabbath observance has diminished in our country over the course of my life, and the country has lost something as a result. I believe that this day—this institution, thousands of years old—is probably more relevant and necessary today than ever before. And it is relevant not just in a religious sense but in a quality-of-life sense, because we’re all working so hard and we never get away from work unless we choose to. We always have our cell phones, our Blackberries, our iPads, or our iPhones with us. This book is an attempt to invite the reader to come with my wife, my family, and me through a typical Sabbath day observed according to a traditional Jewish practice.

I wrote this book in part for Jews who may not be observing the Sabbath as much as I would like, but I really wrote it for people of all faiths—and even for people with no particular faith—hoping that they will decide to accept the gift in whole or in part and bring it into their lives.

At different times in my career my Sabbath observance has intersected with my political life in governmental responsibility because it is different from the rules most people live by. When I first ran for office back in the 1970s and was lucky enough to become a state senator in Connecticut, I made an early decision that I would never be involved in politics on the Sabbath. If I held an office that had governmental responsibilities that I couldn’t delegate, such as voting as a senator or going to a meeting about a national security crisis, I would do that. I was instructed by my rabbis that when life intersects with religious law, life has to triumph, particularly on the Sabbath, which after all is a day in which we are honoring God’s creation of life. How inconsistent it would be if one had the opportunity to protect life—to protect security—and to not do that in observance of a religious law that’s meant to commemorate the Sabbath.

Early on, when I was a state senator and people would ask me to a political event or a testimonial dinner on the Sabbath, I’d say no. Sometimes they were puzzled; other times they were just plain angry, and I would have to explain. But I can tell you that, over time, as they realized I couldn’t come as a matter of religious observance and belief (and that I was doing so consistently), they accepted my answer and respected it. I was different from most of them in those practices, but in the spirit that I think is fundamentally American, those differences did not get in the way of them respecting my beliefs, supporting my career, and, in some sense, even feeling that interfaith bond. Though we were of different faiths, we were joined in a classically American style by a shared belief in God and everything that comes from that.

America, a Faith-Based Initiative

We are now at the start of a presidential campaign in which discussions and debates about the relationship between politics and religion—about the proper place of faith in the public square—have already begun to play a prominent role.

These are not new questions; they are very old. They go back to the founders of our country who wrote the Declaration of Independence and later the Constitution. The words of our founders are relevant because they remind us that from the beginning of America we have been a nation that has defined itself not so much by our geographical borders as by our national values. One of those values was and is a belief shared by most Americans that there is a God. I know that may be controversial to some, because though we have that belief, we respect the rights of those who don’t share that belief. The new nation of the United States of America was formed “to secure these rights”—the rights that are mentioned in the second paragraph of our first document, the rights to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” which are the endowment of our Creator. I always like to say that the truth is that America has been from the beginning a faith-based initiative, and anybody who tries to separate faith from America’s public square is doing something unnatural and ultimately bad for our country.

Our founders were all men of a particular Christian disposition, mostly Protestant, so you have to give them extraordinary credit, for when it came to religion, the remarkable documents they wrote and embraced guaranteed religious freedom for everyone—not just the people who shared their faith. They prohibited the establishment of any one religion, an official religion. They might have been tempted to have an official religion and still give others freedom of religion, but they didn’t—even though Christians were, and are now, a large majority in this country.

The founders were remarkable people. The First Amendment of our constitution prohibits the “establishment” of an official religion and ensures for every American the right to worship (or, as I said, not to worship) as he or she chooses. I was delighted one day with the thought that one of the rights to liberty that our Creator has endowed us with is the right to not believe in the Creator. And though that’s not a right many Americans exercise, it’s a measure of the breadth of the vision of the founders that it is so.

In Article VI of the Constitution of the United States, the founders did something else quite specific to guarantee this vision: They protected every American from religious discrimination in politics by prohibiting what they called religious tests for public office.

The truth is that in many of the original colonies of the United States there were laws saying that you had to be of a particular Christian denomination to run for public office. But, quite remarkably, the founders wanted to rise above that.

Succeeding generations have been inspired by this founding vision and have endeavored to make real its promise—the promise of what I call freedom of religion, not freedom from religion.

Our unique constitutional history created in turn a unique American public square in which there is no establishment of one religion but freedom for all religions. There is the presence of religion in our public life. The greatest laws that are written, including our constitution, are the ones that are so broadly accepted by the people of a nation such as ours that they become not just laws that one feels compelled to follow, because they are in the law, but part of the fiber of the country; they become part of our national system of ethics. So, too, is it with freedom of religion.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the famous French student of America, noted the remarkable religiosity of Americans in his definitive account of the United States written in the nineteenth century. He wrote that there was no country that he had ever seen in which “religion retains a greater influence over the souls of men [I would add, now, women, too] than in America.” He added that “there can be no greater proof of its utility, and of its conformity to human nature, than that its influence is powerfully felt over the most enlightened and free nation of the earth” (Democracy in America, trans. Henry Reeve, vol. 1 [New York: The Century Co., 1898], 388).

I think that is still true today. I saw a recent independent public opinion poll that said that over 90 percent of Americans say they believe in God. I’m always encouraged to see how far ahead of politicians God is running in those polls. And the majority of Americans say that they regularly attend a house of worship.

Alexis de Tocqueville also observed that though Americans were divided into many different religious sects, as he called them, “they all look upon their religion in the same light” (Democracy in America: Part the Second, The Social Influence of Democracy, trans. Henry Reeve [New York: J. & H. G. Langley, 1840], 27). He recognized that though Americans follow many different belief systems, there are universal values that unite us all, and that is a second consequence of our country’s unique commitment to freedom of religion but not freedom from religion.

Faith in the American Public Square

Religious freedom in America in the public square has given birth to the development of a set of shared religious values that were obviously evident in the nineteenth century and, I think, at our best moments, remain so today. President Abraham Lincoln called this America’s “political religion” (Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, ed. Roy P. Basler [New York: The World Publishing Company, 1969], 81), and the poet Walt Whitman praised what he called “a sublime and serious Religious Democracy” in America (Complete Prose Works [Philadelphia: David McKay, 1897], 244).

In American history this sublime and serious combination of religion and democracy has overall been a force for great good. Some of the most important movements of conscience in our history emerged from the convictions of religious people and used the language and liturgy of faith to build popular support. I am thinking of the abolitionist movement in the nineteenth century that led to the end of the evil of slavery. It was that same spirit that motivated much of the suffragist movement in the early part of the twentieth century that fought for and won rights for women in our country. And it was that same spirit that I was personally privileged to witness when I was a college student in the sixties and participated in the civil rights movement led by a religious figure, Dr. Martin Luther King, who invoked America’s political religion, as Lincoln called it, in advancing that noble cause.

I, myself, was inspired to join that movement because of the values it represented, which were deeply rooted in my own faith and religious history: the values of equality, of service, of tolerance, and of respect for law.

It was also while I was at college that another important barrier in America was broken. In the fall of my freshman year a Roman Catholic, John F. Kennedy, was elected to the presidency of the United States for the first time in American history. I will tell you that as a young Jewish American (though I was not thinking of a political career, believe me, at age eighteen), when he won I had some sense that doors had opened for me, that somehow a horizon had expanded for me and for others who were from faiths that were not the majority, for different races, or for other nationalities. I didn’t know how or where that might happen, but I felt inspired and empowered by Kennedy’s election. At that point I certainly wasn’t dreaming yet of being a senator, and I never could have imagined what would happen to me in 2000.

In 2000, then vice president Al Gore gave me the privilege of being the first Jewish American to be nominated for national office when he asked me to be his vice-presidential running mate. In that year I personally experienced so much of what I have described—the American people’s generosity of fairness and acceptance of religious diversity.

The Reverend Jesse Jackson said on the day I was nominated, “Each time a barrier falls for one person, the doors of opportunity open wider for every other American” (“Lieberman on Joining the Democratic Ticket: ‘I Am Humbled and Honored,’” New York Times, 9 August 2000, A16).

I felt that warm sense of shared progress throughout the campaign. I also felt free—as somebody noted recently, freer than Kennedy did in some ways—to talk about my religion and the central role of faith in my life. I wrote about all this in my book, but I want to share a few anecdotes from my book with you that make a larger point, I hope, about the constructive role of faith in America’s public square.

There was a secret service agent who traveled with me during that campaign. He had worked several national campaigns before, and he told me one day that he had never heard so many people saying to a candidate, “God bless you.” I thought about that, and I honestly think it’s a reflection of Christian Americans saying to me in those magical words: “We know you are a religious person. We know you don’t have exactly the same religious faith or observance that we do, but we know we share a common history, and we’re glad you’re running.”

On another occasion, in a slightly more humorous example, I remember speaking to a rally of Latino Americans and seeing in the front row a woman who had created a poster that vividly expressed this sense of shared values and rising together of which I am speaking now. With two powerful words that I don’t think have ever appeared together before, the poster read, “Viva Chutzpah!” That said it all.

In the end the Gore-Lieberman ticket actually received over half a million more votes than the Bush-Cheney ticket—something I enjoyed reminding President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney of very often. Believe me, I do not cite these numbers to relitigate that small matter of Florida’s electoral votes but because I think, like sports, politics ultimately comes down to numbers. So I cite those half million votes as the best—to me, and I hope to everybody—inspiring evidence, unambiguous evidence, that our ticket was judged on the basis of our qualifications and policies and most definitely not on the basis of my religion, because my religion is different, as I said before.

And as I get to the next section of what I want to say, let me describe some of the ways in which my religion is different. You know there is a code; there are rules. There are rules that rabbis created over the centuries to define some of the basic principles in the Torah, the Hebrew Bible, and the Old Testament. For instance, we have pretty rigid rules for observances about what we can eat and drink and when. We observant Jews, particularly women, have a dress code that we’re supposed to follow. Something that is probably not known by many people is that there is even a prescription for Jewish men to wear a particular undergarment. Is this beginning to sound familiar? We have different practices. But the great thing I experienced in 2000 was that those practices were set aside because of all we shared and also because of our national ideals of religious freedom and because we had no religious tests for public office.

A Return to American Founding Principles

In this 2012 presidential election cycle, faith and politics are again going to become a source of some controversy—first in the expression that some have given to their faith (particularly Governor Rick Perry and Congresswoman Michele Bachmann). Some people have real anxiety about that.

I don’t share that anxiety. A candidate does not give up their freedom of religion or freedom of expression when they decide to run for office. They have the right, if they choose, to talk about the role that faith plays in their life, understanding that others (voters) have the right to decide, based on those expressions, whether that affects their view of those candidates. Personally, I always welcome the opportunity to hear about a candidate’s faith and what it means to them because I think it helps me understand them better as a person.

The second religious controversy in the 2012 campaign is, of course, close to BYU. It is that two members of The Church of Jesus Christ Latter-day Saints are running for president: Governor Mitt Romney and Governor Jon Huntsman. And one of them, Governor Romney, a distinguished graduate of this university, may well end up as the Republican nominee.

In these Republican primary campaigns, and in the general election, if Governor Romney is nominated, Americans are going to be challenged again to be true to our founding principles of equality of opportunity and the clear prohibition of Article VI of the Constitution of a religious test being applied for public office.

In 1960, when John F. Kennedy was running for president, there was still significant anti-Catholic prejudice in America. On the eve of the vote, he spoke about this. His words remain quite relevant today—I think this time more relevant to Governor Romney and Governor Huntsman, at least based on some of what I consider to be the prejudicial things that have been said about their faith and its relevance to this campaign. President Kennedy said in the 1960 campaign:

If this election is decided on the basis that 40 million Americans [who happen to be Catholic] lost their chance of being President on the day they were baptized, then it is the whole nation that will be the loser, in the eyes of Catholics and non-Catholics around the world, in the eyes of history, and in the eyes of our own people. [“Address of Senator John F. Kennedy to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association, September 12, 1960”; www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewer/ALL6YEBJMEKYGMCntnSCvg.aspx]

And, of course, the same will be true if Americans judge Governor Romney or Governor Huntsman in the primaries or general election based on their Mormon faith and not on their personal qualities and their ideals and ideas for office.

Just as Americans rose above their prejudices or their discomfort at the differences when Kennedy’s Roman Catholic faith was different in 1960—and sixteen years later when Jimmy Carter’s Christian evangelical faith was different and again in 2000 when my Jewish faith was different—so, too, must Governor Romney be judged, not on the basis of his faith, which may be different to many, but on his personal qualities, his leadership, his experience, and his ideas for America’s future.

My personal experience in 2000, which I have described to you today, gives me great confidence that voters will again reject any sectarian religious tests and show their strong character, their instinctive fairness, and their steadfast belief in the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. And when they do, another barrier may well be broken for another group in America. And the doors of opportunity will thereby open wider for every American.

Regaining Characteristic American Optimism

Now let me conclude by sharing just one more way in which I believe that faith in the public square is profoundly important, not just to the current campaign but to this current difficult time of American life: a time when millions of Americans can’t find work; when millions of other Americans who have work are worried about whether they will still have their jobs next year; when a shocking number of Americans have lost the characteristic American optimism in America’s future; when all too many Americans, an overwhelming majority, unfortunately, for reasons that are understandable, have lost confidence in our government; and when many, both here at home and among our enemies in the world, believe that America has begun an irreversible decline.

In my opinion this pessimism is absolutely unjustified—unjustified by fact or history. I believe that this twenty-first century will be another great century for America. But we must regain confidence in ourselves.

One of the big reasons for my optimism is those numbers I cited earlier: that more than 90 percent of the American people believe in God and more than half of Americans regularly attend houses of worship. Now why is that important? To me it is important—and we have to come back to it as a people to connect our faith with our feelings about our national future—because faith generally leads to hope. The members of the LDS Church whom I have known show every day in their lives a faith that leads to hope and good values and hard work, producing amazingly great results.

Faith in God, love of country, sense of unity, and confidence in the power of every individual—these are the things that have carried the American people through crises greater than the ones we face today and will, I am sure, propel us forward to a better place if only we will return to those values and recognize them as a source of national strength. I hope the presence of faith in the public square will let us do that.

The greatest source of America’s strength and hope for the future is not in the current divisive and rigid politics of Washington. Instead it is in the broadly shared faith and values of the American people and in the reasons for unity and inspiration to serve that so many of us find in the varied houses of worship we attend in this country. We need America’s faith and values to be brought to Washington. We come to Congress, to the White House, and to the administration generally as people of faith. And it seems to me that when we get there, we don’t act as if those principles that I’ve just talked about guide our lives.

I will say to you here in this great center that Brigham Young University for a long, long time now has produced graduates who have understood all of this and spread progress and growth throughout our country and indeed the world. As the old Uncle Sam poster used to say: Your country needs you now—and what you believe in—more than ever. I’m confident that when you go forth from these gates, moved by your faith and enabled by the education you receive here, your work and your service will help make America not only better but help create the more perfect union we have always aspired to be.

I thank you from the bottom of my heart for this great honor and opportunity to be with you this morning, and I pray with you that God will bless us all and our great country, now and into the future. Thank you very, very much.

© Joseph Lieberman. All rights reserved.

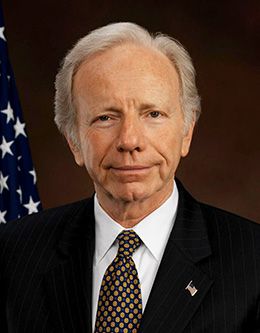

Joseph Lieberman was a senator for Connecticut when this forum address was delivered on 25 October 2011.