Jesus Christ Himself has a care over this school. And why? Because it is a place where the children of the covenant are being prepared for future usefulness in the kingdom of God.

Susan: Greetings! John and I are happy to be here with you on Halloween for this forum.

John: We are especially grateful to share the stand with my former student Justin Collings. Thank you, Justin, for that generous introduction and for these leis. What a surprise!

Susan: We were asked to speak on the mission of Brigham Young University, so this may feel more like a devotional than a forum.

John: We have also tried to connect our talk to Halloween, but it has not been easy to find an uplifting Halloween theme.

Susan: Well, Halloween did begin as a religious festival, All Hallows’ Eve. In fact, in the traditional Christian calendar, Halloween is followed by All Saints’ Day on November 1 and All Souls’ Day on November 2. The whole season is called Allhallowtide. The larger meaning of these holidays is that this is a time to remember the dead, which actually does connect to our topic, fulfilling the dream of BYU. Let’s explore how.

Uplifting Seasonal Themes

John: First, as I have often said, BYU is built on the dreams and hopes of its founders more than most universities are.1 In fact, to continue the Halloween theme, you might say that we are haunted by their dreams. We hope that throughout this Halloween forum you will feel the presence of those who have dreamed the dream of BYU, many of whom have passed away. They had a vision of what the university would become. You inhabit their hopes and dreams. These hopes and dreams are now yours to fulfill. And that is what we want to talk about today.

Susan: Also, while we don’t celebrate Allhallowtide in the Church, it is a good time to remember our own Halloween revelation on the dead, Doctrine and Covenants 138, and a beautiful song in our hymnal, “For All the Saints,”2 which was originally written for All Saints’ Day. This revelation and this hymn provide two additional uplifting connections to these holidays.

John: First, let’s talk about the Halloween revelation. It is fascinating that President Joseph F. Smith’s vision of the dead, Doctrine and Covenants 138, was unanimously accepted by the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve in 1918 on October 31—Halloween! So in a way, it is a Halloween vision. Not only was it ratified on Halloween, but it dramatically clarifies Halloween themes—such as the true nature of the realm of the dead and of our relationship to the dead.3

Susan: For Halloween, John and I have taken to reading Doctrine and Covenants 138 and going to the temple to serve and honor the dead in the Lord’s way. We recommend that you do so as well.

John: A faculty member at BYU–Hawaii heard me make this point and then illustrated it for her class by dressing up as a ghost with signs on her front and back that read, “I am your ancestor” and “Did you do my temple work?”

Susan: We also like to sing “For All the Saints,” so I am really glad we sang it to begin the devotional today. The gorgeous music by Ralph Vaughan Williams is considered “among the finest of twentieth-century hymn tunes.”4 The lyrics are also inspiring. We love both the tune and the text.5

John: We really do. As Susan said, the text was originally written for All Saints’ Day, which is tomorrow in the traditional Christian calendar. We want to apply a line from the hymn’s second verse in the Latter-day Saint hymnal:

Oh, may thy soldiers, faithful, true, and bold,

Fight as the Saints who nobly fought of old,

And win with them the victor’s crown of gold.

Alleluia, Alleluia.6

Brothers and sisters, we challenge you, our beloved BYU community, to be “faithful, true, and bold” in pursuing the mission of BYU. For if BYU is to realize its full potential and become the BYU of prophecy, as President C. Shane Reese invited us to become in his stirring inaugural address,7 we must be “faithful, true, and bold” in fulfilling the dream of BYU.

So now, having made these holiday connections, Susan and I will talk about the dream of BYU itself, including our more than fifty years of personal experience with it and the insights that we have gained from compiling and studying mission-centric talks for a recently published collection entitled Envisioning BYU.8

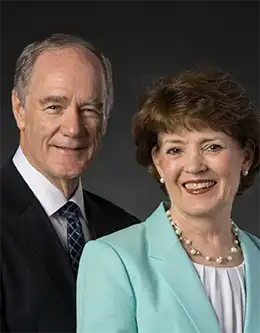

Susan: We are deeply invested in the dream of BYU. It has blessed us as well as many members of our family. Currently it is blessing six of our grandchildren. Here is a photo of those grandchildren as little ones and a photo of them now (with our missionary included) as current BYU students. [Two photos were shown.] We want to address our remarks especially to our grandchildren, some of whom are beginning freshmen, all the way up to those who will soon graduate from BYU to “go forth to serve.”

John: We hope that our comments will help you grandkids—and everyone else who watches or reads this forum—to understand BYUʼs mission. We also encourage you to read and study the talks in Envisioning BYU.

Now Susan will tell you about how she first came to embrace the dream of BYU.

Early Experiences of Embracing the Dream

Susan: As a young girl and as a teenager, I always dreamed of coming to BYU. When I started in the Late Summer Honors Program three weeks before the regular semester began, I felt at every turn that this was the place for me. It was rigorous academically, as a university should be, and everything—the classes, the coursework, the professors, the friendships, the extracurricular activities—was “bathed in the light . . . of the restored gospel.”9 I really felt the Spirit!

One of the early forums I attended articulated my feelings well.10 It was given by Elder Bruce C. Hafen, now an emeritus General Authority Seventy who was then serving as the assistant to the president of the university. In his talk he reflected on how important education was for our early leaders Joseph Smith and Brigham Young. Joseph founded the School of the Prophets and other schools, and Brigham espoused “learn[ing] everything that the children of men know”11 and declared that “our religion . . . circumscribes all the wisdom in the world.”12 They both sought to educate the Saints academically, culturally, and spiritually.

In that forum, Elder Hafen told a handcart pioneer story of Sister Marjorie Pay Hinckley’s grandmother Polly, whose refined family left southern England to come to Zion after they had converted to the Church. As a young girl, Polly sacrificed and suffered so much on that trek, losing three siblings and her mother to death on their journey. Polly later wrote about their condition when they finally entered the Salt Lake Valley. She said:

Early next morning . . . Brigham Young . . . came. . . . When he saw our condition—our feet frozen and our mother dead—tears rolled down his cheeks.

The doctor amputated my toes. . . . The sisters were dressing mother [for her grave]. Oh how did we stand it? . . .

. . . I thought of [my mother’s] words [before we left England], “Polly, I want to go to Zion while my children are small, so they can be raised in the Gospel of Christ. For I know this is the true Church.”13

This family as well as many other families came from cultured cities of Europe. They welcomed a religion that prioritized education and schools along with spiritual knowledge.

Elder Hafen then imagined a fictional evening with pioneers on the plains. These were not rough frontiersmen but cultured and refined Saints who longed for opportunities to learn in the light of the gospel. He said:

Can you imagine with me that perhaps on one of those nights as some of the pioneers came across the prairies, one or two of the older youngsters who liked books (or even Brigham himself, who liked books) might have sat beneath the stars and said to one another, “Do you think that one day there might be a great university in Zion? A great school, with all the books and laboratories and teachers—where the Saints might come from all around the world to learn together? Just think—all those books, and the Spirit too!”14

Elder Hafen continued:

An impossible dream? They might have thought so. But the dream has come true. Let us not forget about . . . the Pollys or the dream. We must take it as seriously as they did. . . . [Just think,] all those books, and the Spirit too.15

The phrase “all those books, and the Spirit too”16 has lingered with me all these years. I recall it often when I participate in this great university that bears the name of its founder, Brigham Young. Here we have the great privilege for an education for our whole souls.17

BYU’s “Prime Directive”: To Teach All Things with the Spirit

John: Thank you for sharing that, Susan. Ever since you told me about Bruce C. Hafen’s forum many years ago and his subsequent devotional in 1991, I have been touched by the phrase “all those books, and the Spirit too.” It has become a kind of watchword for us. I hope that BYU always qualifies to be the school that the early Saints envisioned and sacrificed for.

Recently, in the collection of talks called Envisioning BYU, I have tried to give voice to some of the hopes and dreams of those who built BYU.

As one would expect, the collection includes the famous founding charge from Brigham Young to Karl G. Maeser. Brigham Young said, “Brother Maeser, I want you to remember that you ought not to teach even the alphabet or the multiplication tables without the Spirit of God.”18 You grandchildren should know this founding charge. I like to think of Brigham Young’s charge to teach all subjects with the Spirit of God as BYU’s “Prime Directive”—borrowing a phrase from Star Trek.

Susan: When speaking to the university, President Spencer W. Kimball rephrased President Young’s charge. President Kimball said he expected “that every . . . teacher in this institution would keep his subject matter bathed in the light and color of the restored gospel.”19 Isn’t that beautiful?

Doctrine and Covenants 88: The Olive Leaf and BYU’s “Basic Constitution”

John: It is beautiful, and I love both of those injunctions. They are core. BYU, however, didn’t really begin with Brigham Young’s famous charge to Brother Maeser, nor does Envisioning BYU. BYU has its origin in scriptural injunctions, such as Jesus’s command to love God with all of our mind20 and Joseph Smith’s revelations, especially Doctrine and Covenants 88, known as the Olive Leaf, which contains the oft-quoted counsel to “seek learning, even by study and also by faith.”21 President Dallin H. Oaks called the Olive Leaf “the first and greatest revelation of this dispensation on the subject of education” and BYU’s “basic constitution.”22

Susan: This constitutional revelation is rich in implication for BYU. In our talk today, we will focus on five principles from that revelation:

1. “Cease to be unclean.”23

2. “Teach one another.”24

3. Learn “of things both in heaven and in the earth.”25

4. Learn “by study and . . . by faith.”

5. Live “in the bonds of love” and “covenant.”26

1. “Cease to Be Unclean”

Susan: From the beginning, Latter-day Saints believed worthiness to be essential to education. In Doctrine and Covenants 88:124 we find the clear injunction to “cease to be unclean.” This mandate runs all through the Olive Leaf. There is a repeated emphasis for learners in the School of the Prophets to be clean and to be worthy to qualify for the Spirit. Clearly the expectations of integrity, moral purity, and worthiness did not begin with the current Church Educational System Honor Code. Indeed, like in the temple, those who were received into the School of the Prophets were to be “clean from the blood of this generation.”27 They were received through “the ordinance of the washing of feet.”28

John: Susan, you and I have long been touched by a panel in the exhibit Education in Zion in the Joseph F. Smith Building, which we encourage all of you to visit. The panel shows a washbasin, some soap, and some clean clothing. It explains that early in the morning, students who entered the School of the Prophets would wash themselves and put on clean clothing. Zebedee Coltrin, an early Church leader and student in the school, is quoted: “We came together in the morning about sunrise, fasting, and partook of the Sacrament each time; and . . . we washed ourselves and put on clean linen.”29 They wanted to be clean outwardly and inwardly.

Susan: This is the beginning of a true code of honor. One of my freshman impressions was that my honors colleagues were not just bright students but also honorable people who could be trusted to keep the code of cleanliness and honor to which they had agreed.

John: That’s right. They were people of integrity. Whether or not they agreed with each rule, they had committed to abide by them, so they kept them. That is what integrity means—being whole. It is moral wholeness. Like Dr. Seuss’s Horton the Elephant, they meant what they said and said what they meant.30

2. “Teach One Another”

John: A second principle in the Olive Leaf, in addition to the injunction to be clean, is that students were to “teach one another.” In fact, student and teacher at times exchanged roles, “that all may be edified of all.”31 The idea of students teaching and learning from each other goes back to the earliest days of the Brigham Young Academy. It is in our institutional DNA. Indeed, this principle was implemented through what Karl G. Maeser called the “monitorial system,”32 in which students took responsibility to teach and assist other students.

So, grandkids, I hope that you will have

interactive teaching and learning opportunities here. I strongly encourage you to choose friends and roommates from whom you can learn. I was so blessed to learn together with some remarkable friends and roommates at BYU. One became a Rhodes Scholar and another clerked at the U.S. Supreme Court.

One of them was an honors aide with me. We would talk about ideas late into the night. Not only did we teach and edify one another, but we also sought out-of-classroom experiences to learn from our professors. My roommates and I would sometimes invite favorite professors over to our house for a pancake breakfast and then invite them to tell us about their research. I remember doing this with Frank Fox, who was then a young history professor with a specialty in the American Revolution and the founding of our country. That was great fun. We thought that we were paying Professor Fox in pancakes for doing this. Gratefully he didn’t complain about our doughy offerings.

We also organized a personalized reading class for our honors general education. One roommate, a history major, led discussions on the Federalist Papers. Another, who spoke Danish, led discussions on Søren Kierkegaard’s Training in Christianity. I chose to lead discussions on a book called I and Thou by Martin Buber, of which I had read a snippet in a philosophy class. I still remember the books we taught to each other—maybe better than the books we read for normal classes. My roommates and I taught one another in and out of class. So should you. Don’t be what a Harvard professor called “a bench-bound listener” or learner.33

3. Learn “of Things Both in Heaven and in the Earth”

Susan: A third principle in Doctrine and Covenants 88 is that we are to learn broadly: “of things both in heaven and in the earth, and under the earth; things which have been, things which are, things which must shortly come to pass.”34 Why? “That ye may be prepared in all things.”35 This sounds a lot like a general education curriculum to me.

A broad education is a crucial part of the Olive Leaf. So, in light of the revealed importance of general education, I want to tell you a funny family story that illustrates how passionate John is about general education. It happened when he spoke with our daughter who was preparing to start college. She casually mentioned that she wanted to “get her GEs out of the way.”

John just about went through the roof. He said, “What do you mean ‘get your GEs out of the way’?! You shouldn’t think of college as something you just ‘go through’ for a degree; college needs to go through you.” He went on to say that too often students think of general education as something someone else requires them to do, like soldiers in World War II who were told to pass down a line of people giving them medical shots. They didn’t know why. The shots were just something to be endured, something someone else said was good for them. And that’s how people often experience general education—as something imposed by others, something to get out of the way.

John: That story is a bit embarrassing. My response may have been a little over the top.36 But I actually still feel the same way about that principle, which in fact applies not just to education but to exaltation.37

Too often we describe our goal as going through the temple or making it to the celestial kingdom, rather than having the temple go through us or becoming celestial people, like God. The Lord wants us to become a good person—not just a person who does good things. He wants us to love godliness—not just to grit our teeth and obey. He won’t inflict a celestial life on those who don’t love celestial things. The point is to become celestial people—not just to make it to the celestial kingdom. As President Russell M. Nelson said, we need to “think celestial.”38 We need to become celestial.

It is likewise for education. Too many people conflate college with credentialing. You are not here just to get a credential, as important as that is. The Lord endorsed a stunningly broad education. Why? So “that ye may be prepared in all things when [He] shall send you.”39 You are here to become educated so that you can “go forth to serve.”

Susan: I think you can still feel John’s passion. Now I want him to tell you about how he became so invested in general education at BYU.

John: After my mission I spent a lot of time thinking about what makes an educated person. For a couple of years as an honors aide at BYU, I helped the Honors Program implement an experimental general education program in which students were asked to devise their own GE requirements. They had to write letters to the honors deans justifying their GE categories and courses they wanted to take based on what they thought an educated person should know. I read these justifications every day and ghost-drafted possible responses for the deans. This meant I had to think long and hard about the what and the why of education, especially from a BYU perspective and a gospel perspective.

Susan: You didn’t know it at the time, but I think the Lord was preparing you for another later assignment that would help define the dream of BYU. When you were asked to join the administration in the early 1990s, the academic vice president, Todd Britsch, and the provost, Bruce Hafen, assigned you to draft a statement about what a BYU education should do for students.

John: At first I thought, “Why?” We already had a beautiful mission statement that President Jeffrey R. Holland had drafted a few years before.40 Wasn’t that enough?

No, I was told. We needed a statement focused on student outcomes, such as that all students should learn to write. This assignment triggered memories of drafting those GE letters, and that got me started.

At the time I also had a deep impression—almost a revelation—that I should connect what students should learn at BYU to Brigham Young’s educational vision. After all, the university bears his name. So I read Hugh Nibley’s essays describing Brigham Young’s views on education. With all this in mind, I set about drafting what became The Aims of a BYU Education.41 As you study the aims, note that each aim begins with a quote from Brigham Young. This was deliberate.

Susan: I hope you are familiar with the four aims of a BYU education. The first aim is that it should be “spiritually strengthening,”42 which ties to Brigham Young’s original charge to Karl G. Maeser to teach nothing here “without the Spirit of God.”

The next aim is “intellectually enlarging,”43 which was described by Brigham Young when he said, “Every accomplishment . . . in mathematics, music, and in all science and art belong to the Saints.”44

The third aim is “character building.”45 Brigham Young espoused “a firm, unchangeable course of righteousness”46 in integrity, sportsmanship, honesty, fairness, and all moral virtues.

And the final aim of a BYU education is that a BYU education should lead to “lifelong learning and service.”47 Our founder said, “When shall we cease to learn? I will give you my opinion about it; never, never.”48 About service, he stated, “Our education should . . . make us of greater service to the human family.”49

John: We didn’t know at the time I drafted the aims that a paradigm shift was coming that would sweep across higher education. It was a shift from a “teaching paradigm,” which looks at inputs such as class sizes and faculty credentials, to a “learning paradigm,” which looks at student outcomes.50 Soon all institutions of higher education would be required to articulate what they expected their students to learn.

Susan: I think the aims helped BYU meet the challenge of a new era, and they have held up very well over the years. We encourage you to study the BYU mission statement and the aims so that these ideals are embedded in your souls—now, as you study here, and also later, when you leave this hallowed place.

John: Recently when Elder D. Todd Christofferson spoke to the university about the aims, he recognized that they point outward to lifelong learning and service. He said that a BYU education should lead to “the end of shared service in the cause of Christ.”51 This outward orientation is also deliberate.

Our prophet, President Nelson, has taught this by word and example. Think of how much he learned after his initial degree—he wasn’t in it just for credentialing—and of how he has used his education to bless others. He said, “Education is the difference between wishing you could help other people and being able to help them.”52 He also said, “We educate our minds so that one day we can render service of worth to somebody else.”53

Elder Christofferson added: “Learning is not an end unto itself but a means to bless God’s children.”54

4. Learn “by Study and . . . by Faith”

Susan: President Nelson is such a beautiful example of lifelong learning and service. Let’s turn briefly to a fourth educational principle from the Olive Leaf: to learn “by study and . . . by faith.” This combination is crucial at BYU and to education for Latter-day Saints generally. The Lord expects us to learn with both our intellect and our spirit.

I love the way President Kimball described this when he addressed the university at the beginning of its second century. He said that we should be “bilingual”: “You must speak with authority and excellence . . . in the language of scholarship, and you must also be literate in the language of spiritual things.”55 I hope that you cultivate the bilingual education of the whole soul that you can receive here.

I know what it is like to have to study really hard to learn. I also know what it is like to have the Spirit enlighten my mind. One of my favorite visual reminders of this principle is found on a sign in a stairwell inside the Harold B. Lee Library that quotes the scripture “seek learning, even by study and also by faith.”

John: When I see that sign, I also note the worn stairs, which for me symbolize the pursuit of learning by study. I also think of the countless prayers that have ascended to heaven from the library and from the classrooms of BYU as students also seek to learn by faith.

Susan: We have walked those stairs and we have said those prayers hundreds and hundreds of times.

John: We have worn the grooves in those stairs, as have you, I hope. This always reminds me of what happens at the university on Sundays. As a student and later as a campus bishop, I attended wards in which the sacrament was laid out and blessed between Bunsen burners, and I partook of the sacrament in a room that had the periodic table on the wall. The sacrament amidst Bunsen burners and the periodic table—what an image of joining study and faith! Every Sunday, when the campus turns into a church, it is evident that we belong to an institution deeply committed to developing bilingual disciples who know how to learn “by study and also by faith.”

5. Live “in the Bonds of Love” and “Covenant”

Susan: Now before we leave our discussion of section 88, let us talk about a beautiful fifth principle of Latter-day Saint education: namely, that we are to interact “in the bonds of love” and “covenant.”

I love this conclusion of Doctrine and Covenants 88, which describes a formal salutation by the “president, or teacher,”56 of the School of the Prophets—who was Joseph Smith—to his students. He greeted them “in the bonds of love” and “covenant” with these words:

Art thou a brother or brethren? I salute you in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, in token or remembrance of the everlasting covenant, in which covenant I receive you to fellowship, in a determination that is fixed, immovable, and unchangeable, to be your friend and brother through the grace of God in the bonds of love, to walk in all the commandments of God blameless, in thanksgiving, forever and ever. Amen.57

John: That stirs me to my very soul. Can you imagine the Prophet greeting you in the name of Christ and in covenantal fellowship as you entered the school? We don’t greet students this way now at BYU, but we should retain the spirit of this salutation in our hearts. I would often repeat it to myself as I prepared to interact with my students, and I encourage all faculty and staff to do the same. Like the School of the Prophets, this community should be bound together “in the bonds of love” and “covenant”; it should be a place where we strive “to walk in all the commandments of God blameless, in thanksgiving.” This should be a place of covenant belonging.

Temple and School

Susan: Likewise, Joseph said that the School of the Prophets was to be “a sanctuary . . . of the Holy Spirit,”58 like BYU59 and the temple. Interestingly, it is nearly impossible to tell if the Lord was talking about school or temple in Doctrine and Covenants 88 when He commanded the Saints to build a house of prayer, fasting, faith, learning, glory, and order—“a house of God.”60 I think it is meant to apply to both.

John: I do too. That’s why I included temple prayers that reference BYU in Envisioning BYU. So I hope you will come to see and feel a connection between school and temple at BYU and that you will participate in temple ordinances often as an important part of your education.

In the Doctrine and Covenants, the Lord indicated that a Church school was to be held in the upper room of the temple in Kirtland.61 Nowadays every Church school is located beside a temple. I love the beautiful twin murals in the exhibit Education in Zion. They visually pair the first Latter-day Saint temple with BYU and depict both structures as enveloped in heaven’s light. There is and ought to be a spiritual connection between school and temple for Latter-day Saints. After all, both are called houses of learning in the scriptures. Church schools should strive to be worthy of their temple neighborhoods. I often said that at BYU–Hawaii, and I say it here too.

Before we leave these accounts of the early builders of BYU, Susan will tell you about a vision recorded by Brigham Young’s daughter Zina P. Young Williams Card. It is a vision about BYU that has touched us both deeply.

Christ Has “a Care over This School”

Susan: The early years of the Brigham Young Academy were fraught with challenges, including financial hardships, and the prophet who had had the vision for this school had passed away. Brigham Young’s daughter Zina, an early graduate of the academy who later became a faculty member and the first dean of women, was very anxious about the success of the academy. She traveled to Salt Lake City to pour out her school worries to President John Taylor.

He lovingly took her into his private library and said:

My dear child, I have something of importance to tell you that I know will make you happy. I have been visited by your father. He came to me in the silence of the night clothed in brightness and, with a face beaming with love and confidence, told me . . . that the school being taught by Brother Maeser was accepted in the heavens and was a part of the great plan of life and salvation; that Church schools should be fostered for the good of Zion’s children . . . , for they would need the support of this knowledge and testimony of the gospel, and there was a bright future in store for the preparing . . . the children of the covenant for future usefulness in the kingdom of God; and that Christ Himself was directing and had a care over this school.62

Each time I hear this beautiful story, it thrills my heart. Think of it! Jesus Christ Himself has a care over this school. And why? Because it is a place where the children of the covenant are being prepared for future usefulness in the kingdom of God. I wish that every student and all others who walk this campus would keep the words “Christ Himself has a care over this school” running through their minds. I think it would inspire gratitude for the opportunity to study in a place that is cared for by Christ Himself and would prompt them to ask themselves: “What is my role and responsibility in helping this school reach its destiny? What can I do to live up to the privilege of being here? And how can I fulfill the dream of BYU?”

An Impossible Dream?

John: I love the vision that Zina recounted! What a thrill to learn that Christ has a care over this school.

In his second-century address, which I hope you all will read, President Kimball said that BYU has a “rendezvous with history.”63 He then shared a remarkable statement by a Christian president of the United Nations, Charles H. Malik, who said he believed one day that

a great university will arise somewhere . . . to which Christ will return in His full glory and power, a university which will, in the promotion of scientific, intellectual, and artistic excellence, surpass by far even the best secular universities of the present, but which will at the same time enable Christ to bless it and act and feel perfectly at home in it.64

Is this an impossible dream? You might think so, commented President Henry B. Eyring in a BYU address, had not President Kimball then said, “Surely BYU can help to respond to that call” to be a university where Christ can feel at home.65 President Eyring then explained that Christ will feel at home at BYU only if we are consecrated:

We know something of what a place must be like for the glorified Savior to feel perfectly at home. . . . Those who labor there . . . will have long before consecrated it to Him and to His kingdom. . . .

. . . He will be at home, perfectly at home, because they will not only have said the words “This is the Lord’s university,” but they will have served and lived to make it so. They will have made it a consecrated place, offered it to Him.66

This is our dream to fulfill. Prophets and university leaders have helped keep the dream alive for us. They have invited us, as did Justin Collings in his inspiring BYU devotional, to “seek holiness, seek learning, seek revelation, seek the best gifts, seek Christlike exemplars, and, above all, ‘seek this Jesus of whom the prophets and apostles have written.’”67 It is He who has a care over this school.

Fulfill the Dream

Susan: We hope that you now, more than ever, feel surrounded by the spirits of those who have built BYU. Great, noble men and women have built this place. Sometimes they were paid in cabbages and carrots. But they were consecrated. They believed in BYU. They believed that Christ Himself has a care over this place.

May you be “faithful, true, and bold” in fulfilling their dream of BYU, like all those “Saints who nobly fought of old.”

John: As you leave, you will hear the carillon bells. The carillon was dedicated by President Kimball at the end of his prophetic second-century address. Every time I hear the bells, I remember what President Kimball said in his prayer when he dedicated them: “Just as these bells will lift the hearts of the hearers . . . , let the morality of the graduates of this university provide the music of hope for the inhabitants of this planet.”68

Brothers and sisters: this is our dream to fulfill—to become the music of hope for an increasingly discordant world! The bells call you and me to be faithful, true, and bold as we pursue the dream of BYU. In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

Notes

1. See John S. Tanner, “A House of Dreams,” BYU annual university conference faculty session address, 28 August 2007; also in Foundations and Dreams, ed. John S. Tanner, vol. 1, Envisioning BYU (Provo: Brigham Young University, 2022), 237–52.

2. See “For All the Saints,” Hymns, 2002, no. 82.

3. For a more extensive discussion of Joseph F. Smith’s Halloween revelation, see my essay “A Halloween Vision of the Dead” (31 October 2019), in John S. Tanner, Pacific Ponderings: July 2015 to June 2020 (self-published, 2020), 123–25.

4. Emily R. Brink and Bert Polman, eds., “Hymn No. 505: For All the Saints,” Psalter Hymnal Handbook (Grand Rapids, Michigan: CRC Publications, 1998), 677.

5. The author of the text, Bishop William Walsham How, indicated that his poem was written for All Saints’ Day. In the heading to his poem, Bishop How originally included the phrase “a cloud of witnesses” and a reference to Hebrews 12:1, which follows the great catalog of the faithful in Hebrews 11 and reads:

Wherefore seeing we also are compassed about with so great a cloud of witnesses, let us lay aside every weight, and the sin which doth so easily beset us, and let us run with patience the race that is set before us. [emphasis added]

The lyrics of the hymn invite all to join this cloud of witnesses (see Brink and Polman, “For All the Saints,” 676–77). The first version of this hymn was published as “Saints’-Day Hymn” in Horatio Nelson (3rd Earl Nelson), comp., Hymn for Saints’ Days, and Other Hymns (London: Bell and Daldy, 1864), 40–43.

6. “For All the Saints,” Hymns; emphasis added.

7. See C. Shane Reese, “Becoming BYU: An Inaugural Response,” address delivered at his inauguration as BYU president, 19 September 2023.

8. The collection includes volume 1, Foundations and Dreams (2022), and volume 2, Learning and Light (2024). The talks in the collection are also available on the BYU Speeches website.

9. Spencer W. Kimball, “Education for Eternity,” address to BYU faculty and staff, 12 September 1967; also in Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 173.

10. See Bruce C. Hafen, “Reflections on Being at BYU,” BYU forum address, 22 January 1974; published in Best Lectures 1973–74 (Provo: Associated Students of Brigham Young University Academics Office, 1975), 41–53.

11. Brigham Young, “Remarks,” Deseret News, 4 June 1873, 276; JD 16:77 (25 May 1873).

12. Brigham Young, “Remarks,” Deseret News, 19 September 1860, 226; JD 8:162 (2 September 1860).

13. Life of Mary Ann Goble Pay, autobiographical sketch, typescript, Archives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City; also “Mary Goble Pay Autobiography,” in Arthur D. Coleman, comp., Pay-Goble Pioneers of Nephi, Juab County, Utah (Salt Lake City: n.p., 1968), 81, 91. Quoted in Hafen, “Reflections”; in Best Lectures, 52.

14. Hafen, “Reflections”; in Best Lectures, 52–53.

15. Hafen, “Reflections”; in Best Lectures, 53.

16. Bruce C. Hafen gave another address at BYU about twenty years later with this phrase as its title: see Hafen, “All Those Books, and the Spirit, Too!” BYU annual university conference address, 26 August 1991.

17. See C. Terry Warner, “An Education of the Whole Soul,” BYU devotional address, 11 November 2008; also in Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 275–87.

18. Brigham Young, quoted in Reinhard Maeser, Karl G. Maeser: A Biography by His Son (Provo: Brigham Young University, 1928), 79; also in Maeser excerpt, “Brigham Young’s 1876 Charge to Karl G. Maeser,” Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 13–14.

19. Kimball, “Education for Eternity”; also in Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 173.

20. See Matthew 22:37; Mark 12:30; Luke 10:27.

21. Doctrine and Covenants 88:118.

22. Dallin H. Oaks, “A House of Faith,” BYU annual university conference address, 31 August 1977; also in Learning and Light, ed. John S. Tanner, vol. 2, Envisioning BYU (Provo: Brigham Young University, 2024), 5, 6.

23. Doctrine and Covenants 88:124.

24. Doctrine and Covenants 88:77, 118.

25. Doctrine and Covenants 88:79.

26. Doctrine and Covenants 88:133.

27. Doctrine and Covenants 88:138.

28. Doctrine and Covenants 88:139.

29. Zebedee Coltrin, in “Minutes, 1883 August–December,” School of the Prophets Salt Lake City meeting minutes, 3 October 1883, 59, Archives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City; see also Merle H. Graffam, ed., Salt Lake School of the Prophets Minute Book, 1883 (Palm Desert, California: ULC Press, 1981), 38.

Here is the full quote by Zebedee Coltrin:

Every time we were called together to attend to any business, we came together in the morning about sunrise, fasting, and partook of the Sacrament each time; and before going to school we washed ourselves and put on clean linen.

30. See Dr. Seuss, Horton Hatches the Egg (New York: Random House, 1940). Horton the Elephant repeatedly says:

I meant what I said

And I said what I meant. . . .

An elephant’s faithful

One hundred per cent!

31. Doctrine and Covenants 88:122.

32. See Karl G. Maeser, “The Monitorial System,” Church School Department, Juvenile Instructor, 1 March 1901, 153–54; also Maeser, School and Fireside (Salt Lake City: Skelton and Co., 1898), 25, 37, 249, 272. See exhibit Education in Zion in the Joseph F. Smith Building on the BYU campus; see also A. LeGrand Richards, Called to Teach: The Legacy of Karl G. Maeser (Provo: BYU Religious Studies Center and Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 230–32, 418–23.

33. Jerome S. Bruner, “The Act of Discovery,” On Knowing: Essays for the Left Hand (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 1962), 83.

34. Doctrine and Covenants 88:79.

35. Doctrine and Covenants 88:80.

36. My response was so over the top because my daughter’s statement took me by surprise. We had never said such a thing to her. She was clearly repeating something that someone else had told her—that she should “get her GEs out of the way.” I didn’t want her to shortchange college by focusing only on the credential. She is a bright, ready, natural learner—an example to the whole family. For instance, at BYU she once read three or four young adult novels a week while carrying a full course load. That is something I could have never managed.

37. See many talks by Dallin H. Oaks, including his seminal general conference address “The Challenge to Become,” Ensign, November 2000.

38. Russell M. Nelson, “Think Celestial!” Liahona, November 2023.

39. Doctrine and Covenants 88:80.

40. See The Mission of Brigham Young University (4 November 1981).

41. See The Aims of a BYU Education (1 March 1995).

42. Aims of BYU.

43. Aims of BYU.

44. Brigham Young, “Instructions,” Deseret News, 15 July 1863, 17; JD 10:224 (April and May 1863).

45. Aims of BYU.

46. Brigham Young, “Remarks,” Deseret News, 16 May 1860, 81; JD 8:32 (5 April 1860).

47. Aims of BYU.

48. Brigham Young, “Discourse,” Deseret News, 27 February 1856, 402; JD 3:203 (17 February 1856).

49. Brigham Young, “Discourse,” Deseret News, 19 April 1871, 125; JD 14:83 (9 April 1871).

50. See Robert B. Barr and John Tagg, “From Teaching to Learning—A New Paradigm for Undergraduate Education,” Change 27, no. 6 (November/December 1995): 12–25.

51. D. Todd Christofferson, “The Aims of a BYU Education,” BYU university conference address, 22 August 2022.

52. Russell M. Nelson, “‘Youth of the Noble Birthright’: What Will You Choose?” CES devotional for young adults, 6 September 2013, churchofjesuschrist.org/broadcasts/article/ces -devotionals/2013/01/youth-of-the-noble -birthright-what-will-you-choose.

53. Russell M. Nelson, “The Message: Focus on Values,” New Era, February 2013.

54. Christofferson, “Aims of a BYU Education.”

55. Spencer W. Kimball, “The Second Century of Brigham Young University,” BYU devotional address, 10 October 1975; also in Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 46.

56. Doctrine and Covenants 88:128.

57. Doctrine and Covenants 88:133.

58. Doctrine and Covenants 88:137.

59. For more on the connection between the School of the Prophets and BYU, see Oaks, “A House of Faith.” See also Jeffrey R. Holland, “A School in Zion,” BYU annual university conference address, 22 August 1988.

60. Doctrine and Covenants 88:119. In the dedicatory prayer for the Provo Utah Temple on February 9, 1972, Joseph Fielding Smith referred to Brigham Young University as “that great temple of learning” (in “Dedication Prayer of Provo Temple,” Church News, 12 February 1972, 5; also “Provo Temple Dedicatory Prayer,” Ensign, April 1972).

61. See Doctrine and Covenants 95:17.

62. John Taylor, quoted in Zina Presendia Young Williams Card, “Short Reminiscent Sketches of Karl G. Maeser,” unpublished typescript, 3; in Zina Presendia Young Williams Card papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University; emphasis added; text modernized. Also in excerpt “Accepted in the Heavens,” Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 156. See also quoted text in Paul Thomas Smith, “John Taylor,” in Leonard J. Arrington, ed., The Presidents of the Church: Biographical Essays (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1986), 109.

63. Kimball, “Second Century”; also in Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 53.

64. Charles H. Malik, “Education in Upheaval: The Christian’s Responsibility,” Creative Help for Daily Living 21, no. 18 (September 1970): 10; quoted in Kimball, “Second Century”; also in Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 53.

65. Kimball, “Second Century”; also in Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 53; quoted in Henry B. Eyring, “A Consecrated Place,” BYU annual university conference address, 27 August 2001.

66. Eyring, “A Consecrated Place.”

67. Justin Collings, “A Certain Idea of BYU,” BYU devotional address, 1 February 2022; quoting Ether 12:41.

68. Kimball, “Second Century”; also in Envisioning BYU: Foundations and Dreams, 59.

John S. Tanner, former president of BYU–Hawaii and former academic vice president of BYU, and Susan W. Tanner, former Young Women general president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, delivered this forum address on October 31, 2023.