Brigham Young: A Bold Prophet

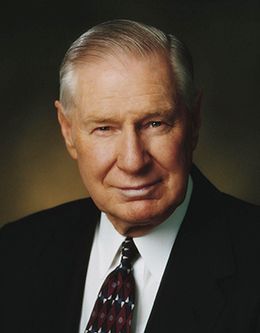

Second Counselor of the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

August 21, 2001

Second Counselor of the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

August 21, 2001

Brigham Young died with the name Joseph upon his lips. He spoke of him and his work in these words: “I honor and revere the name of Joseph Smith. I delight to hear it; I love it.

I am pleased to be here and help all of you memorialize a great leader whose birth 200 years ago we celebrate. Much has been written and said about Brigham Young and his great leadership and accomplishments. There is little that has not been thoroughly pored over, analyzed, and commented upon. To present some history about this great leader that is not so well known, I asked Ron Esplin for his able assistance, and I am indebted to him for much of the material I am using.

One evening in early 1859, after the peaceful conclusion of the Utah War—a keen test of leadership for Brigham Young—the ordeal was being discussed and the men in Brigham Young’s office were talking about the game of chess. President Young remarked that he “knew nothing of such games.” But then he added, “I have had to play with the kingdoms of the world, with . . . living characters.” When some observed that he had played “a great game,” he replied, “Yes, and I am not displeased with nor regret any move that I have made” (17 February 1859, Brigham Young Office Journal, LDS Church Archives).

I have chosen to focus on what appears to me to be the source of his absolute self-confidence and the complete certainty he had in his own judgment. I know of no other explanation for his boldness and audacity in thinking of moving a whole people—more than 60,000—by wagon and handcart across much of the North American wilderness to the Great Basin. As President Hinckley said:

No plow had even broken its soil. He knew nothing of its fertility, nothing of the seasons, the weather, the frost, the severity of the winters, the possibility of insect plagues. Jim Bridger and Miles Goodyear had nothing good to say concerning this place. Sam Brannan pleaded with him to go on to California. He listened to none of them. He led his people to this hot and what must have appeared as a very forlorn place. When he arrived, he looked across this broad expanse to the salt lake in the west and said, “This is the right place.” [Gordon B. Hinckley, Brigham Young 200th birthday anniversary gala, 1 June 2001, unpublished]

Brigham Young was present, along with Wilford Woodruff and others, when the Prophet Joseph Smith said:

“Brethren, I have been very much edified and instructed in your testimonies here tonight, but I want to say to you before the Lord, that you know no more concerning the destinies of this Church and kingdom than a babe upon its mother’s lap. You don’t comprehend it.” . . . He said, “It is only a little handful of priesthood you see here tonight, but this Church will fill North and South America—it will fill the world.” . . . “It will fill the Rocky Mountains. There will be tens of thousands of Latter-day Saints who will be gathered in the Rocky Mountains. . . . This people will go into the Rocky Mountains; they will there build temples to the Most High.” [Joseph Smith, quoted by Wilford Woodruff, CR, April 1898, 57; punctuation and spelling modernized]

How could Brigham Young have been so sure when he told Wilford Woodruff, upon entering the valley, “This is the right place. Drive on”? The answer is that as the Valley of the Great Salt Lake came into view, Brigham Young was seeing much more than the salt flats and the swarms of black crickets. Sometime later Wilford Woodruff described their entrance into the valley in these words:

When we came out of the cañon into full view of the valley, I turned the side of my carriage around, open to the west, and President Young arose from his bed and took a survey of the country. While gazing on the scene before us, he was enwrapped in vision for several minutes. He had seen the valley before in vision, and upon this occasion he saw the future glory of Zion and of Israel, as they would be, planted in the valleys of these mountains. When the vision had passed, he said: “It is enough. This is the right place. Drive on.” [Wilford Woodruff, in The Utah Pioneers (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Printing and Publishing Establishment, 1880), 23; quoted in B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Century One, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1930), 3:224]

I believe this is why Brigham Young summarily ignored the comments of Jim Bridger, Miles Goodyear, and Sam Brannan. Without a second thought Brigham Young dismissed Sam Brannan’s entreaties to take the Saints on to California. His certainty that the Valley of the Great Salt Lake and the Great Basin was the right place rested upon the higher intelligence he had received in the vision before they started.

Brigham Young has been recognized by many for his leadership ability. Even critics and nonmembers regarded him as a great colonizer. Characterized by some as the practical sage, he was also a man of great faith, and I believe that it was his profound faith that was at the very heart of his success as a leader. With this profound faith came a sense of confidence, not only in the rise of the Church and the growth of the kingdom but also in his own role as a prophet and leader.

Having been a keen observer of the Prophet Joseph Smith and of many of the events of the Restoration, Brigham bore strong witness that the leadership keys had been left with the Twelve after the Prophet was martyred—indeed, that the Lord had “commanded [Joseph Smith] to endow the Twelve with these keys and priesthood” (Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, comp. Bruce R. McConkie, 3 vols. [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954–56], 1:259). In the dark days following the Martyrdom, Brigham reminded the Saints, “You cannot appoint a prophet; but if you let the Twelve remain and act in their place, the keys of the kingdom are with them and they can manage the affairs of the church and direct all things aright” (8 August 1844, in HC 7:235). He also told the Saints that if they would not sustain the Twelve, then the Twelve would raise up a people who would! That showed how much confidence he had in the Twelve. He knew they had the keys, the commission, and the responsibility to build on the foundation Joseph had laid.

Brigham and the apostles all knew the importance of completing the Nauvoo Temple, and with their example and enthusiasm, construction work accelerated. The fire of their enthusiasm brought rapid progress and feelings of great joy in seeing their goal coming to pass. However, as their enemies saw the walls go up, they felt threatened and vowed to drive them out before their beloved temple could be finished. In the midst of this angry furor, Brigham Young inquired of the Lord whether they should stay and finish the temple. He recorded in his diary: “The answer was we should” (24 January 1845, Brigham Young Office Files, 1832–1878, LDS Church Archives).

Brigham Young remained calm. “I am composed,” he told the Nauvoo Legion before some of them took the field, “nor has the late disturbance had any effect upon me” (quoted by Hosea Stout, 17 September 1845, in On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1844–1861, ed. Juanita Brooks, 2 vols. [Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1964], 1:65).

Clearly Brigham Young was sustained by inner strength and spiritual gifts. He was a man such as Joseph Smith once described who enjoyed a personal promise from God that was

as an anchor to the soul sure & steadfast. Though the thunders might roll, & lightnings flash & earthquakes Bellow & war gather thick around yet this hope & knowledge would support the soul in evry hour of trial trouble & tribulation. [Joseph Smith, quoted by Wilford Woodruff, 14 May 1843, in Wilford Woodruff’s Journal: 1833–1898 Typescript, ed. Scott G. Kenney, 9 vols. (Midvale, Utah: Signature Books, 1983–1984), 2:231]

The construction continued despite the threats of the mob, and rooms of the temple were dedicated as they were completed. As the Saints began to receive their temple blessings, Brigham Young said to those being endowed:

[If you (that is, the Twelve and others endowed before the completion of the temple)] will be as diligent in prayer as a few has been I promise you in the name of Israels God that we shall accomplish the will of God and go out in due time from the gentiles with power and plenty and no power shall stay us. [Brigham Young, quoted by William Clayton, 7 December 1845, in An Intimate Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton, ed. George D. Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1995), 194]

History shows that the Saints surely did go out from the presence of their enemies and found the place that God had prepared for them.

As he led the Saints across the American wilderness, Brigham Young believed strongly that this journey to the West was the Lord’s errand—therefore they could not fail. But being the practical man that he was, he knew that success had a price. It could only come with diligence, sacrifice, and hardship. And he understood that, even with their best efforts, they could not do it alone—they would need God’s help. But his great faith and sense of purpose brought him both confidence and peace during the winter and spring of 1847 as he prepared for the long trek West.

Part of President Young’s unwavering confidence came because he knew the plan was not his own. As he told the Saints nearly 10 years later after their arrival in the valley, “I did not devise the great scheme of the Lord’s opening the way to send this people to these mountains.” Who did? “It was the power of God that wrought out salvation for this people,” he insisted. “I never could have devised such a plan” (JD 4:41 [31 August 1856]).

Further tests of President Young’s faith were still in store. The severest one came during 1857 and 1858 as thousands of U.S. troops—one-third of the standing army of the United States—marched to Utah escorting Alfred Cumming, who had been sent to replace Brigham Young as governor. President Young knew only too well from their experience in Missouri what enemies can do when backed by military authority. Yet he was confident that if the Saints did all in their power, the Lord would help them. President Young declared martial law and mobilized the territorial militia to do everything short of bloodshed to slow down the advancing troops. Grasslands and supply wagons were burned, provisions and cattle confiscated, and the advance units harassed day and night. Still they kept coming—ever nearer—until winter struck in their favor as the timely arrival of heavy snows stopped the army in its tracks, forcing it into winter camp 80 miles from Mormon settlements.

Brigham Young recognized that his leadership was not flawless. “There are weaknesses manifested in men that I am bound to forgive,” he said on one occasion. “I am right there myself. I am liable to mistakes,” he continued, saying he was just as set in his feelings as any man alive, but “I am where I can see the light. I try to keep in the light” (30 April 1860, Manuscript History of the Church, LDS Church Archives). The assurance he felt was not that he would never make mistakes or would always know what was best but that, in the end, God oversees the essential. He quickly abandoned what did not work well for something that might work better, but his ultimate direction and destination remained unchanged. Long-term goals based on revelation provided a balanced consistency in his day-to-day decisions and gave him the confidence to press forward regardless of the obstacles or even the errors.

Sometimes his bold and powerful leadership was disconcerting. For example, after his dangerous winter journey to the Salt Lake Valley to mediate peace with the army, Colonel Kane was at first offended when Brigham Young rejected his counsel. However, when Kane finally agreed to do whatever President Young told him to do, this is what Brigham said of that incident:

I told him as he had been inspired to Come here he should go to the armey and do as the spirit led him to do and all would be right and he did so and all was right.

He thought [it] vary strange because we were not afraid of the armey. I told him we were not afraid of all the world. If they made war upon us the Lord was able to deliver us out of their hands and would do it if we did right. [Brigham Young, quoted by Wilford Woodruff, 15 August 1858, in Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 5:209]

A few months after the peaceful resolution of the Utah War, President Young walked past the temple grounds to the Staines Mansion—now the Devereaux House—to visit Governor Cumming. Concerned that they had narrowly averted disaster, the fair-minded governor cautioned Brigham Young to refrain from provocative or rash acts in the future. The president replied, “With all due respect to your excellency, . . . I do not calculate to take the advice of any man that lives, in relation to my affairs.” Although he recognized he had friends and counselors to advise him during such crises, he made it plain that in God alone would he trust. “My religion is true,” he told the governor solemnly, “and I am determined to obey its precepts while I live.” He would, he insisted, “follow the council of my heavenly Father, and I have faith to follow it, and risk the consequences.” He concluded, “You may think strange of it, but you will yet see that I am right” (24 April 1859, Manuscript History of the Church, LDS Church Archives; see also B. H. Roberts, Comprehensive History of the Church, 4:517–18).

Understanding Brigham Young’s religious conviction and the religious context within which Latter-day Saints responded to him is essential to an understanding of his leadership. As one visitor to his office recorded and others noted, Brigham Young had amazing self-confidence and “absolute certainty of himself and his own opinions” (Fitz Hugh Ludlow, The Heart of the Continent: A Record of Travel Across the Plains and in Oregon [New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1870; New York: AMS Press, 1971], 368). This certainty stemmed from his conviction that he was doing God’s work. He believed that if he and other mortals did all they could to establish the kingdom, God would see to the rest. This makes understandable his firmness and calm, unshakable optimism in the face of seemingly impossible circumstances.

The skeptical but perceptive Frenchman Jules Remy recognized that Brigham Young, being clearly

convinced of the truth of the religion he has embraced, . . . has set before him, as the object of his existence, the extension and the triumph of his doctrine; and this end he pursues with a tenacity that nothing can shake, and with that stubborn persistence and ardent ambition which makes great priests and great statesmen. [Jules Remy and Julius L. Brenchley, A Journey to Great-Salt-Lake City, 2 vols. (London: W. Jeffs, 1861; New York: AMS Press, 1971), 1:497]

The leadership of “the eminent politician and the able administrator” was at root religious, Remy and his companion were forced to conclude, and they left him “perfectly convinced of the sincerity of his faith” (Remy, A Journey, 1:495; 2:303).

Brigham was a firm believer in faith and works. He knew from the start that if the Saints did their part, the Lord would do the rest (see JD 6:328–29 [6 April 1854]; JD 3:154 [6 May 1855]; JD 5:293 [4 October 1857]). Brigham Young showed his faith by expending every energy and resource on good works before turning to God for assistance. That was part of the program, what God expected, and what was necessary if man was to develop. Don’t ask God to protect you from Indians if you are unwilling to build forts, he counseled. Man is left alone, he taught, “to practise him to depend on his own resources, and try his independency” (28 January 1857, Brigham Young Office Journal, LDS Church Archives).

Folklore has preserved this attitude in the story of President Young overlooking the valley with an admiring minister: “What you and the Lord have done with this place is truly amazing,” observed the visitor, to which President Young replied, “Yes, Reverend, but you should have seen it when the Lord had it alone!” Man was to use all his skills and effort and energy for the kingdom, and if that was not enough, then he might ask for God’s intervention.

Though proud of his down-to-earth but formidable talents, Brigham Young gave credit to God for the gift of them. “I know how I received the knowledge that I have got,” he said in 1866. Recalling his early years with Joseph, “I had but one prayer, and I offered that all the time. And that was that I might be permited to hear Joseph speak on doctrine, and see his mind reach out untramelled to grasp the deep things of God.” He maintained that “an angel never watched him closer” and that he “would constantly watch him and if possible learn doctrine and principle beyond that which he expressed.” It required several years of this close attention to the Prophet, he declared with some exaggeration, “before I pretended to open my mouth to speak at all” (Brigham Young, 8 October 1866, general conference address, Historian’s Office Reports of Speeches, LDS Church Archives). Brigham Young took care to never “let an opportunity pass of getting with the Prophet Joseph and of hearing him speak in public or in private, so that I might draw understanding from the fountain from which he spoke.” “This,” he insisted, “is the secret of the success of your humble servant” (Brigham Young, JD 12:269–70 [16 August 1868]).

President Hunter told me of a time many years ago when he heard of an elderly man who had worked on the Salt Lake Temple as an engineer when he was a young man. This engineer was not a member of the Church and was for a time in Salt Lake City before going on to his destination in California. The engineer recalled seeking an appointment with President Brigham Young—in those days visitors sat on a bench and moved along the bench as they waited for an appointment with the president. The engineer wanted counsel from the president regarding a construction problem on the temple. Brigham Young made furniture and did carpentry, and so he knew a few practical things about construction; he had an eye for things of that kind. But he had never constructed a building like the temple. On this occasion he looked at the plan for a part of the Salt Lake Temple that this engineer had brought. He drew a line in the shape of an arc and said, “This is the way to construct it.” As I remember it, the engineer never joined the Church but testified, “You can’t tell me Brigham Young was not a prophet.”

In the early days of the Church, many fell away because they would not sustain Joseph Smith as the Lord’s anointed. In fact, the Prophet Joseph said of the leaders in Kirtland that “there have been but two but what have lifted their heel against me—namely Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball” (HC 5:412). Because of their faithful loyalty, the Lord called Brigham Young to lead the Church out West, and when the First Presidency was reorganized, Heber C. Kimball was called as first counselor to Brigham Young.

Brigham Young died with the name Joseph upon his lips. He spoke of him and his work in these words: “I honor and revere the name of Joseph Smith. I delight to hear it; I love it. I love his doctrine” (JD 13:216 [17 July 1870]). “I feel like shouting hallelujah, all the time, when I think that I ever knew Joseph Smith, the Prophet whom the Lord raised up and ordained” (JD 3:51 [6 October 1855]). “I am bold to say that, Jesus Christ excepted, no better man ever lived or does live upon this earth. I am his witness” (JD 9:332 [3 August 1862]).

In the marvelous experience of Brigham Young in February of 1847, when the Prophet Joseph appeared to him in a dream or vision, Brigham pleaded to be reunited with him. Brigham Young asked him if he had a message for the Brethren. The Prophet Joseph Smith said:

Tell the people to be humble and faithful, and be sure to keep the spirit of the Lord and it will lead them right. Be careful and not turn away the small still voice; it will teach you what to do and where to go; it will yield the fruits of the kingdom. Tell the brethren to keep their hearts open to conviction, so that when the Holy Ghost comes to them, their hearts will be ready to receive it.

The Prophet further directed Brigham Young as follows:

They can tell the Spirit of the Lord from all other spirits; it will whisper peace and joy to their souls; it will take malice, hatred, strife and all evil from their hearts; and their whole desire will be to do good, bring forth righteousness and build up the kingdom of God. [23 February 1847, Manuscript History of Brigham Young: 1846–1847, ed. Elden J. Watson (Salt Lake City: Elden Jay Watson, 1971), 529]

I add my witness to the great prophetic leadership of Brigham Young and testify that that prophetic leadership and the keys of that office have remained in the Church and rest upon our great prophet in this day and time, President Gordon B. Hinckley. May we always be found following the counsel and direction of our prophets I pray in the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

James E. Faust was the second counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this Education Week address was given on 21 August 2001.