Adversity is the refiner’s fire that bends iron but tempers steel.

It is always a special thrill and blessing to come upon this campus. My message today is simple, but one which you may not wish to hear. I have chosen to speak concerning the blessings of adversity. The theme was best expressed by the Lord when he said, “Be patient in afflictions, for thou shalt have many; but endure them, for, lo, I am with thee, even unto the end of thy days” (D&C 24:8).

During the past two years, and indeed for about five years of my life, I have lived in countries where most of the people are far below the poverty level of the United States. During this last period of time, as President Oaks indicated, we made our home in São Paulo, Brazil. During most of that time our neighbor to the north was constructing a new home. The carpenters, the tile setters, the plumbers, and the cabinet workers on that house received far below what we know as the minimum wage. In fact, some lived in a shack on the site. There was cold running water available from the end of a hose, but no warm or hot water. Their work day was from 6:00 a.m. till about 5:30 p.m. This meant that at about 5:00 in the morning they would begin to prepare their meals and get ready for work.

My college-age daughter, Lisa, could not help complaining that she was awakened almost every morning by their clarion-voiced singing. They sang, they laughed, they chattered—only occasionally unpleasantly—the whole day through. When I explained to Lisa how little money they made and how little they had she made an interesting observation, “But Dad, they seem so happy.” And happy they were. Not one owned an automobile, nor even a bicycle—just the clothes on their backs—but they found life pleasant and fulfilling. We were reminded again how little it takes to make some people happy.

Many years ago when I was practicing law, I organized a company for one of the new car dealers in this area. I served as his legal counsel and a corporate officer for many years, and one of my sons has taken over my responsibilities as legal counsel. Recently we were both at his place of business. I noticed the rows and rows of beautiful, shiny, gleaming expensive new cars. Out of concern I mentioned to the proprietor that if he did not get those cars sold, the finance charges would be exorbitant and eat up the profits. My son said, “Dad, don’t look at it that way. Look at all the profit those cars will bring.”

While I think he was more right than I, it suddenly occurred to me that my son had never been through a depression. We looked at the problem through different eyes because I am a child of the Great Depression. I cannot forget what a merciless taskmaster debt is.

For some years we lived by a very skilled mechanic and his choice family. He was a specialist. He and his wife resolved never again to go into debt. This resolution was born of a bitter memory: when they were newly married and had their small family the depression came along, and skilled as he was he could not find a job. His home, along with the homes of many others, was foreclosed; and they lived through the depression in a chicken coop made reasonably comfortable through his mechanical skills.

We now have a generation many of whom perhaps have not fully known nor appreciated the refining blessings of adversity. Many have never been hungry because of want. Few have been forced not to do things because they did not have the money. Yet I am persuaded that there can be a necessary refining process in adversity which increases our understanding, enhances our sensitivity, and makes us more Christlike. Lord Byron said, “Adversity is the first path to truth” (The International Dictionary of Thoughts, p. 11). The lives of the Savior and his prophets clearly and simply teach how necessary adversity is to achieve a measure of greatness.

Edmund Burke defined it well when he said:

Adversity is a severe instructor, set over us by one who knows us better than we do ourselves, as He loves us better, too. He that wrestles with us, strengthens our nerves and sharpens our skill. Our antagonist is our helper. This conflict with difficulty makes us acquainted with our object and compels us to consider it in all its relations. It will not suffer us to be superficial. [The International Dictionary of Thoughts, p. 11]

I would suppose that many of you students are having a difficult time making ends meet. Indeed, it may be very painful. It would, from your standpoint, be unkind to say that this experience may be good for you and may be remembered in more affluent times warmly and even with some fondness. One of my more successful cousins went through law school using much candlelight because he and his bride could not afford electricity to light the rooms.

The present general counsel of General Motors is a black. Without question he holds one of the most lucrative and prestigious positions for lawyers in all of the world. He was a poor boy and was required to obtain his education through heroic efforts and under circumstances that were difficult in the extreme. He was required to work one and two jobs regularly and, if I am not mistaken, occasionally three. He was asked if he felt uncomfortable among the highest-paid executives of the world; his answer was no. He said that most of them had been poor boys like him who had worked their way up, being tested, challenged, threatened, and discouraged. Adversity is the refiner’s fire that bends iron but tempers steel.

It would appear that the shortage of energy will change our life styles. The president of Texaco, Mr. John McKinley, some time ago explained to a group in which I was present that in the United States, and even in the world, there are abundant sources of energy. But it will require that these be harnessed, and it will be more expensive because of the capital it takes to convert that energy into usable forms. This means that we will not be able in the future to be so profligate and wasteful of energy.

Hopefully, the quality of life will improve. It may mean that to be happy we are not going to be able to rely upon physical comforts and to satisfy our whims, but must learn to draw upon inner strengths and inner resources. It will likely mean that we will find our entertainment and pleasure in simpler things that do not cost money and are closer to home. Hopefully, it will mean the development of untapped inner strengths and resources that will bring an inner peace and a self-understanding so articulately explained by Anwar Sadat in a recent essay which no doubt many of you read in Time magazine. He related his experience of being confined in a British jail. Like Sadat, hopefully we will find ourselves and like ourselves better, be more at peace with our surroundings, and appreciate more our fellowmen. We will become less sated with the material and the mechanical and learn to cultivate a taste for bread and milk.

President David O. McKay said:

Today there are those who have met disaster which almost seems defeat, who have become somewhat soured in their natures; but if they stop to think, even the adversity which has come to them may prove a means of spiritual uplift. Adversity itself may lead toward and not away from God and spiritual enlightenment; and privation may prove a source of strength if we can but keep the sweetness of mind and spirit. [David O. McKay, Treasures of Life, pp. 107–8]

May I suggest a few things which might be done to prepare us for a time when we are less affluent and possibly happier.

1. Wean ourselves away from dependence for our happiness upon mere material and physical things. This could mean a bicycle instead of a car, and walking instead of a bicycle. It may mean skim milk instead of cream.

2. Learn to do without many things and have some reserve to fall back on. A recent article in Indiana concerning the present coal crisis and telling of a member of the Church there, a coal miner with a year’s supply, brought much publicity and attention in the newspapers.

3. Develop an appreciation for the great gifts of God as found in nature, in the beauty of the seasons; the eloquent testimony of God in the sunrise and the sunsets, the leaves, the flowers, the birds and the animals.

4. Engage in more physical activity that does not employ the use of hydrocarbons, including walking, jogging, swimming, and bicycling.

5. Have a hobby that involves your mind and your heart and can be done at home.

6. Pay your tithes and offerings. The keeping of this commandment will not insure riches—indeed, there is no assurance of being free from economic problems—but it will smooth out the rough spots, give the resolution and faith to understand and accept, and create a communion with the Savior which will enhance the inner core of strength and stability. “Who hath not known ill fortune never knew himself or his own virtue,” said David Mallett (The International Dictionary of Thoughts, p. 12).

7. Develop the habit of singing or, if this is not pleasant, whistling. Singing to oneself will bring less comment and question than talking to oneself. My father one time came home from a deer hunt empty-handed, but his heart was renewed and his spirit lifted. He recounted with great appreciation that one of his companions had frightened the deer away because he was always singing trumpet-voiced to himself as he walked through the pines and the quaking aspen. Father was more enriched by the mirth of the song than by the meat of the venison.

In life we all have our Gethsemanes. A Gethsemane is a necessary experience, a growth experience. A Gethsemane is a time to draw near to God, a time of deep anguish and suffering. The Gethsemane of the Savior was without question the greatest suffering that has ever come to mankind, yet out of it came the greatest good in the promise of eternal life. One of the lessons learned by the Savior in his Gethsemane was declared by Paul to the Hebrews:

Though he were a Son, yet learned in obedience by the things which he suffered:

And being made perfect, he became the author of eternal salvation unto all them that obey him;

Called of God an high priest after the order of Melchizedek. [Hebrews 5:8–10]

The image of the Savior to many from a public relations standpoint was described by Isaiah: “He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not” (Isaiah 53:30).

Perhaps in all literature, sacred or profane, there is none more eloquent than the 121st, 122nd, and 123rd sections of the Doctrine and Covenants received and written by Joseph Smith the Prophet while in the Liberty Jail in the spring of 1839.

O God, where art thou? And where is the pavilion that covereth thy hiding place?

How long shall thy hand be stayed, and thine eye, yea thy pure eye, behold from the eternal heavens the wrongs of thy people and of thy servants, and thine ear be penetrated with their cries?

Yeah, O Lord, how long shall they suffer these wrongs and unlawful oppressions, before thine heart shall be softened toward them, and thy bowels be moved with compassion toward them?

[Then comes the promised relief:] My son, peace be unto thy soul; thine adversity and thine afflictions shall be but a small moment;

And then, if thou endure it well, God shall exalt thee on high; thou shalt triumph over all thy foes.

Thy friends do stand by thee, and they shall hail thee again with warm hearts and friendly hands.

Thou art not yet as Job; thy friends do not contend against thee, neither charge thee with transgression, as they did Job. [D&C 121:1–3, 7–10]

Out of these circumstances also came the great promise of verse 26 in this same section: “God shall give unto you knowledge by his Holy Spirit, yeah, by the unspeakable gift of the Holy Ghost, that has not been revealed since the world was until now.”

But the Prophet Joseph Smith was warned:

The ends of the earth shall inquire after thy name, and fools shall have thee in derision, and hell shall rage against thee;

While the pure in heart, and the wise, and the noble, and the virtuous, shall seek counsel and authority, and blessings constantly from under thy hand.

And the people shall never be turned against thee by the testimony of traitors. [D&C 122:1–3]

In this adversity also came these great truths recorded in the 121st section:

Hence many are called, but few are chosen.

No power or influence can or ought to be maintained by virtue of the priesthood, only by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned;

By kindness, and pure knowledge, which shall greatly enlarge the soul without hypocrisy, and without guile—

Reproving betimes with sharpness, when moved upon by the Holy Ghost [I am not always able to determine when I am “moved upon by the Holy Ghost”]; and then showing forth afterwards an increase of love toward him whom thou hast reproved, lest he esteem thee to be his enemy;

That he may know that thy faithfulness is stronger than the cords of death.

Let thy bowels also be full of charity towards all men, and to the household of faith, and let virtue garnish thy thoughts unceasingly; then shall thy confidence wax strong in the presence of God; and the doctrine of the priesthood shall distil upon thy soul as the dews from heaven.

The Holy Ghost shall be thy constant companion, and the scepter an unchanging scepter of righteousness and truth; and thy dominion shall be an everlasting dominion, and without compulsory means it shall flow unto thee forever and ever. [D&C 121:40–46]

Why is adversity often such a good schoolmaster? Is it because adversity teaches so many things? Through difficult circumstances we are often forced to learn discipline and how to work. In often unpleasant circumstances we may also be subjected to a buffeting, honing, and polishing that can come in no other way. Most of your leaders in the General Authorities are familiar with adversity. They have not been and are not exempt. Allow me to illustrate by telling you something of three that I have selected only because of their great familiarity with difficulty.

Early in life, President Kimball learned the necessity of work. He had many painful experiences in his early years preparatory to his great ministry. As a young boy he nearly drowned once, suffered Bells Palsy, lost his mother through death, while still a young man lost his beloved sister Ruth, and shortly after marriage contracted smallpox, at which time Sister Kimball counted 125 pustules on his face.

He learned early about financial reverses and lost some investments. Like Job, he suffered from boils which continued for many years, and on one occasion came onto his nose and lips. Once he suffered 24 boils at one time; and not long thereafter he began to suffer the excruciating pain of heart attacks that recurred for many years and finally resulted in open-heart surgery. He became bothered by a hoarseness in his voice; it was relieved through a blessing of the Brethren, but it later returned along with the boils. A serious cancer in the vocal cords, it required surgery and thereafter voice training and cobalt treatments. Also, the Bells Palsy returned temporarily and skin cancers had to be removed.

The result of his refiner’s fire was that he came forward with a refined spirit, a sensitive and understanding heart, and a kindness and humility that are unparalleled. President Kimball can be described in the words which the Lord spoke concerning Job. May I read in the book of Job, substituting the name Spencer for Job: “Hast thou considered my servant [Spencer], that there is none like him in the earth, a perfect and an upright man, one that feareth God, and escheweth evil? And still he holdeth fast his integrity, although thou movedest me against him, to destroy him without cause” (Job 2:3).

I have always been interested in the background of President Eldon Tanner. At this University some years ago, President Tanner recalled his humble and difficult beginnings. Speaking of his parents, he said,

When they arrived in Southern Alberta, Father had no money, and he had to sell his team in order to finance. But the thing I have always been pleased about was that Father never thought of calling on the government. He went and worked for his neighbor, and he broke horses so they would have horses to use. He lived in a dugout on a homestead where I lived the first part of my life. He often said, “I bet ten dollars against a quarter section of land of the Dominion Government that I could make a go of it. I nearly succeeded.” He also said, “You know, when I came to this country [referring to Canada] I didn’t have a rag on my back; now I am all rags.”

[President Tanner continues,] We lived after that in a little hamlet. I don’t suppose this would be of interest to you, but in that little hamlet we didn’t even have a telephone. We didn’t have a daily paper; we didn’t have a weekly paper—regularly. We had no running water—hot or cold water. So you can imagine other things we didn’t have! We had no central heating, you can be sure of that. In fact, I often wondered if we had any heating in the house. [President Nathan Eldon Tanner, “My Experiences and Observations,” speech given at Brigham Young University, May 17, 1966]

From these difficult beginnings came the giant we know as Nathan Eldon Tanner. He was a speaker of the Alberta Legislature, Minister of Mines and Lands in the province, president of the Trans-Canadian Pipeline, branch president, bishop, stake president, Assistant to the Council of the Twelve, apostle, and counselor to four Presidents of the Church.

I should like to share with you an incident or two in the early life of President Marion G. Romney, best told in his own words:

I’m a Mexican by birth. I was born in Colonia Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico. My parents happened to be down there at the time. I was raised there until I was about fifteen years old. During the last two or three of those years, the Madero Revolution was in progress. The rebels and the federalists were chasing each other through the country; each taking everything we colonists had, by way of arms and ammunition and by way of supplies. Finally we were forced to leave. I came out of Mexico with the Mormon refugees in 1912.

I remember I had a very thrilling experience on the way from where we lived to the railroad station about eight miles south of Colonia Juarez. We went in a wagon. . . . I was riding with my mother and her seven children and my uncle (her brother) and his family of about five or six children. . . . We had one trunk—that was all we were able to bring. I was seated on the trunk in the back of the wagon. . . . The Mexican rebel army was coming up the valley from the railroad station toward our town. They were not in formation. They were riding their saddle horses. Their guns were in the scabbards. Two of them stopped us and searched us. They said they were looking for guns. We didn’t have any guns or ammunition. They did find $20 on my uncle—pesos, not dollars. . . . They took that and waved us on. They went up the road about as far as from here to the back of this room, stopped, turned around, drew their guns from their scabbards, and pointed them down the road at me. As I looked up the barrels of those guns, they looked like cannons to me. They didn’t pull their triggers, however, as evidenced by the fact that I am here to tell the story. That was a very thrilling experience! One of my maturing experiences.

[President Romney continues,] The rebels blew up the railroad track after the train we were on passed over it. Later, Father and the rest of the men came out to El Paso, Texas, on horseback. We never returned nor did we recover any of our property while my father lived.

Father and I went to work to earn a living for his large family. There were no welfare programs then. We had a difficult time making a living. We had to “root hot” or die.[Marion G. Romney, speech at Salt Lake Institute of Religion, October 18, 1974]

I had the opportunity to see how well President Romney handles a trowel when he laid the cornerstone for the São Paulo Temple. President Romney said, “Going to school but part time, it took me from 1918 to 1932 to get through college.”

After he was married and his family was started, he worked full time at the post office in order to provide for his family while he went through law school. In these difficult conditions his marks were so high and his scholarship so excellent that he was later admitted to the Order of the Coif. The Order of the Coif admits only the most distinguished law scholars. I was never invited to join that organization.

Someone has said that among the law students the “A” students make the professors, the “B” students make the judges, and the “C” students make the money. President Romney and I both proved that adage wrong because President Romney did not become a law professor and I did not make a fortune. He practiced law and became a bishop, stake president, one of the first Assistants to the Twelve, a member of the Council of the Twelve, and, as we know, has given great service as a counselor in the First Presidency to two Presidents. He has demonstrated his great love and compassion for people through his many years of guidance in the welfare program of the Church.

Indeed, the difficult and adverse experiences of these three Brethren are comparable to experiences in the lives of many others of your leaders, and I have mentioned only these three because it seemed to me that their familiarity with adversity was more than ample.

Thomas Paine wrote:

I love the man who can smile in trouble, who can gather strength in distress and grow brave by reaction. ‘Tis the business of little minds to shrink, but he whose heart is firm, and whose conscience approves his conduct, will pursue his principles to the death.

I wish to invoke the blessings of the Almighty God upon you choice and chosen young people who are held in such high esteem. Much is expected of you. Do not presume, because the way is at times difficult and challenging, that our Heavenly Father is not mindful of you. He is rubbing off the rough edges and sensitizing you for your great responsibilities ahead. I ask his blessings to be upon you spiritually, and pray that your footsteps might be guided along the paths of truth and righteousness. I promise you the rich and rewarding blessings of selfless service, and wish you to know that by the personal gift of the Holy Ghost I have come to know that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that he was crucified for the sins of the world.

I wish to conclude as I began, “Be patient in afflictions, for thou shalt have many; but endure them, for, lo, I am with thee, even unto the end of thy days.” In the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

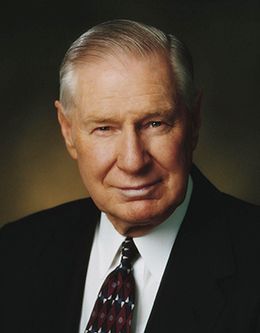

James E. Faust was a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 21 February 1978.