“If you can feel what it is like to be a student and feel their pains and afflictions, you can make a great difference, a moral difference, in how they feel about who they really are and what they can become.”

You Are All Teachers

I am grateful to have been invited here tonight for many reasons. One reason is that I was able to bring my wife and my daughters. My wife Kathy loved the years I was a university professor. Wistfully, from time to time she asks, “Will we ever go back to the campus?” So every time you invite me here with her, you are moving forward my courtship. I am delighted that she could be here and that we are with you, as teachers, tonight.

Now, some of you may wonder if I know that you are not all on a list of the faculty; but you all are teachers. My two sons, the first two that came here, probably feel as close to and as cared about by the people in the admissions office as they do their teaching faculty. I have another son who decided what this university was like from the way he was treated in the dorms, before he ever went to a class.

I once was the janitor in the Mines and Mineral Industries Building at the University of Utah. My supervisor there may have given me more lasting lessons than I got from the Physics Department. And the Physics Department did a lot for me.

What It’s Like to Be a Student

My wife Kathy may not think of herself as having been a teacher at Ricks College. While I was there, I taught a class each term. I keep meeting our former students; occasionally they will say they attended one of the classes I taught. More often they will say, “Do you remember when we came to your house?” Then they will describe an evening. Those students remember, and they appreciate Kathy. So I’d say to the spouses who are here, and to all of us: When we so much as speak to a student, we are teachers. Tonight I would like to try, if the Spirit will allow me, to help us all remember what it is like to be a student. Do you remember starting at some school? Each of us could tell a story. I grew up in Princeton, New Jersey. I can remember how my cousins helped me. When I moved from New Jersey to Salt Lake City to go to public school, my cousins from the West said the kids would stone me with my New Jersey accent. I got rid of it quickly, out of fear. I remember terror as I walked up to the junior high school on the first day.

A few years later—I don’t know how it happened—but after basketball season I left high school and went without my high school classmates to the University of Utah. I can remember those first days—the Physics Department and the Mathematics Department didn’t seem very friendly to me. I remember my fear.

I went from there to the United States Air Force and somehow decided that physics would not be my life’s work. I thought I needed something else for education so I tried a place I had heard of called the Harvard Graduate School of Business. I was so naïve I didn’t know it might be hard to be admitted. I know now that it was a miracle that I was accepted.

I can remember parting from my father on a street corner in New York City. For some reason he was there for scientific meetings. I was on my way to the Harvard Business School in my Ivy League suit, or so I thought. That suit was later borrowed by my roommate, who had been a Harvard undergraduate. He wore it to a costume party as a gangster suit, which offended me some. He wore a black shirt and a white tie with it.

When I parted from dad in my new suit, it was one of those great moments in life when I was going off to school. I looked back at him. Later he said to me that I looked forlorn, but I remember feeling sorry for him. To him I was a frightened student. I didn’t know what a balance sheet was. I didn’t know what a pro-forma cash flow looked like. I was a physics student about to be lost in the Harvard Business School.

From there I went to Stanford University. Kathy was nice enough to marry me. Her first adventures in cooking for us were to find some morning menu that I could keep down on my nervous stomach as I went off to meet those apparently confident Stanford students. I wondered how I could teach them, until I found out that they were scared, too.

You remember the interesting contrasts of your life as a student. I have emphasized the fear, which is probably a better thing to think about when you were with students. But the other side is there, too. I can remember sometimes when I thought I knew a very great deal. Sometimes I thought I knew so much that I bordered on feeling I could “know for myself,” as the scriptures say. I suppose all of us as students and as teachers see that interesting swing, which we all seem to make at times. Sometimes we feel so overwhelmed that we are sure we can’t learn; at other times we know so much that almost no one can teach us. I don’t think we are looking for some middle ground; that is not what we are looking for. Rather, there is another place, almost a magic place, not halfway between being terrified and being vain, but another place where both vanity and fear are muted, not simply balanced.

I saw it once in a meeting of the American Chemical Society in New York City. Some of you would perhaps not know my father was a well-known chemist. At one time he was president of the American Chemical Society. I thought he was quite a fellow and would be immune to any sort of criticism.

My father was presenting a paper at this meeting. In the middle of his presentation, someone stood up and interrupted him. I didn’t think that was the way things were done, but apparently this man stood up in front of everyone and said, “Professor Eyring, I have heard you on the other side of this question.” I am not reproducing the sting that it had to it. It had a cut to it. I could feel the electricity. I thought: “Oh, I am seeing my father attacked in public, and I know he has a temper. Oh dear, oh dear. What might happen here.” At least I knew if I had spoken to him that way, I would have had quite an experience. But Dad laughed in the most pleasant way. He chuckled and said: “Oh, you are right. I have been on the other side of this question. Not only that, but I have been on several sides of this question. In fact, I will get on every side of this question I can find until I can understand it.” And on he went in his presentation, as happily as could be. Now that was much more than a clever rejoinder. That was a glimpse for a moment of that happy place which I think is best described this way: He took delight in struggling with what he didn’t know because he had no feeling of limits on what he might know. That made him not only a powerful learner, but someone who was not in much danger of quitting because he was afraid or fearful. He was also not in much danger of feeling that he knew so much he couldn’t be taught.

When people would call him humble, my mother would respond: “You don’t know him. He is the most self-assured man I have ever known.” And both descriptions were true. I don’t know if it was the magic of his mother’s rearing. I think she had something to do with it. She always told him he was perfect. His sisters are here this evening, and they know he wasn’t. They also know their mother said that to him, and that he believed it. Isn’t that strange that he would. My mother didn’t say it as often, if at all, which bothered him a little. He took “perfect” in an interesting way. He always thought of himself as a little boy, as a child with so much to learn. He was always willing to put aside the last theory he had propounded. He regularly felt, “I have been on every side of this question, and I will get on every side I can discover until I get a better answer.”

My guess is that what matters most, as you and I try to help our students, will not be so much whether they master a particular subject or pass our exam. That will matter some, but what will matter most is what they learn from us about who they really are and what they can really become. My guess is that they won’t learn it so much from lectures. They will get it from feelings of who you are, who you think they are, and what you think they might become.

Let me describe to you a teacher. He is someone I would like very much to be like. I got a book from him recently. Some of you in the room know him, and you may have gotten the book, too. It is called Education for Judgment. He is one of the editors. His name is C. Roland Christensen.

I wish he were here tonight. I wish I had the chance to sit again at his feet. Let me give you the feeling of what that would be like by reading to you a few lines. One is not in the book itself. It is in the flyleaf. Now remember, this was written to me. I am reading it not because I deserve the praise, but because he makes me believe that someday I will. You can’t get the flavor of this unless you realize that this is a man who is a university professor at Harvard. That is not simply a professor in the university, but one of the few that Harvard names what they call university professors, with the right to teach a course anywhere they choose to in the university. As far as I know, he is the first ever appointed by the university from the Business School.

I was his student more than 30 years ago. I have seen him only twice in the years since. I am one of thousands of his students, and yet listen to what is in the flyleaf.

To: Hal Eyring

Friend

Colleague

Teacher—not simply to the mind but to the spirit and soul of his many students. With respect, admiration, and appreciation.

Chris

Harvard University

July 10, 1991

He tried to get me to call him Chris. Others do, but I never will. It isn’t just a mark of respect for me. It is that I am afraid that if I did I might lose the magic spell of his faith in me, which still draws me on.

Let me read to you a few lines from what he wrote in the book. I have chosen these lines at random. As I read them. I would like you to think of a scripture. Professor Christensen may have seen it once. I don’t know if he really knows what it means as well as you do, but somehow he has discovered its meaning. Listen to the scripture.

“Let no man deceive himself. If any man among you seemeth to be wise in this world, let him become a fool, that he may be wise” (1 Corinthians 3:18).

That scripture describes that special place I want to be in, and you want your students to be in, where you are a fearless learner and also not in much danger of being vain. If that is what it means to give a student a great education, and I think it is, then listen to the words of C. Roland Christensen about how that can be done. I have taken them out of context, but they stand well alone.

Teaching as a Moral Act

“I believe that teaching is a moral act” (C. Roland Christensen, Education for Judgment, p.117).

Then, in another place: “To me, faith is the indispensable dimension of teaching life. Why, then, is it so rarely mentioned?” (p. 116).

And then this: “I believe in the unlimited potential of every student. At first glance they range, like instructors, from mediocre to magnificent. But potential is invisible to the superficial gaze. It takes faith to discern it, but I have witnessed too many academic miracles to doubt its existence. I now view each student as ‘material for a work of art.’ If I have faith, deep faith, in students’ capacities for creativity and growth, how very much we can accomplish together. If, on the other hand, I fail to believe in that potential, my failure sows seeds of doubt. Students read our negative signals, however carefully cloaked, and retreat from creative risk to the ‘just possible.’ When this happens, everyone loses” (p. 188).

Now may I say simply that I think he is right. Teaching is a moral act. Faith is indispensable to teaching. We hardly know the potential of our students, but we send them signals each time we doubt and each time we believe. You might ask, “What does that have to do with this fall, my classes, my students, and the people that I will see.” I would answer that this way.

I wish I could have been here for President Lee’s talk that he gave at the beginning of this conference. He was nice enough to send a copy to me. I read it very carefully. I assume it will be published. I saw in it opportunity of the most exciting kind. There are three things, particularly, I wanted to point out tonight. Not only did he sketch, at least for me, all the opportunity anyone could ever want who sees teaching as a moral act, but also he did it in a way that makes me admire him even more. Let me take them one at a time.

One of the things that he said had to do with admissions of students. I, as a member of the board of trustees, was blessed to be in the room where some of the things that he mentioned in that talk were decided. I would say two things. One is that he was accurate in describing not just the acquiescence of the board but the complete sharing of the desires he described with you. Also, I must say to President Lee and to those around him that that happened in an almost miraculous way. The board includes busy men with much to be concerned about in their sacred callings. A meeting was called to deal with issues of a rather intricate kind. It was lengthy. It would be so easy for them not to have the experience, which they did have, which I really believe brought down the powers of heaven. I have been in many meetings. I don’t think I have ever seen the unanimity and the feeling of confidence that “this is right” any more clearly and firmly than I felt in that meeting.

Let me choose two of the things he talked about that came from that meeting, and one other that he planned to use in his talk. The first one had to do with students being admitted. Here is what I read in President Lee’s talk. He described how we would admit students. “We can reach beyond strictly numerical criteria in making our admissions decisions, and that those decisions affect so many people in so many important ways that the risks of departure from strict objectivity may be warranted. At least we are willing to give it a try, and our experience this year was encouraging” (President Rex E. Lee, Annual University Conference Address, August 26, 1991).

What that is saying in practical terms is that there was, with the board’s enthusiastic support, a commitment to find a way to admit some students who will have done less well on tests and will have done less well on high school grades than their fellow students, with whom they will compete. There will be a wider range of what we call academic abilities. To some extent that has always been true. There have always been students here who have struggled, and you have all worked with them in various ways. This is a decision to seek to admit more students who will feel—at least as they begin with you—almost overwhelmed.

It is for that reason perhaps that I see such a great opportunity. Think of Professor Christensen and think of the signals that you can send.

I would like, if I might, to suggest a simple scripture that perhaps you may never have applied before in quite the way that I think you can. Do you remember what it was like to be told you were wrong or that you didn’t understand when you weren’t sure you could do the work at all? My life was marginal, as I viewed it, in the Physics Department of the University of Utah. Some of those professors had a way of emphasizing to me my inadequacies. And some didn’t. May I make a suggestion that you can be one who can lift, not crush. May I suggest a scripture to guide you. It is one you know well.

Reproving betimes with sharpness, when moved upon by the Holy Ghost; and then showing forth afterwards an increase of love toward him whom thou hast reproved, lest he esteem thee to be his enemy. [Doctrine and Covenants 121:43]

I have done what a number of you have probably done. I have tried different dictionaries on the word “betimes.” I found at least three meanings that might give some encouragement to you.

One interesting meaning for betimes is “early.” Might I suggest that if you will watch and if you will seek to be moved upon by the Holy Spirit, you will know which of your students are in trouble. Don’t wait too long. Many of them will dig holes so deep they will never get out. Go to them early with help.

A second meaning of the word betimes is “timely,” or “at the right time.” Might I suggest that generally, particularly for the very fragile, the right time is when others aren’t around. I know how busy you are. I know that you are saying: “Oh, Brother Eyring, come on. With the load I have, with the number of students, with the things I have to do, don’t you know you are asking an impossible thing?” I know it is hard, but I will give you this encouragement. You don’t have to have a private interview with every student in trouble, every time. In fact, for many of those students it will be rare that anyone ever did it. If you reach out, now and then, and just enough of you do, the university will be for them a different place. And the help may matter less than that the help was offered.

Now I would give you this other suggestion that “betimes” sometimes means “not too frequently.” I suppose what that means is be careful as you visit with them that you don’t always talk only about their failures. You see, what touched me about that inscription from Professor Christensen is that he left out all of my weaknesses and instead described the hints he sees in me of what I might become.

In a few years people may ask: “Well, did the experiment work? Did the attempt to admit students with a wider range of abilities work?” The answer is: It all depends on you. If you simply drop them in the caldron of competition, give them the same kinds of tests, do the same kinds of things that perhaps made them predict to be a little poorer students, then they will turn out not to be good students. And you can brand them failures very easily. On the other hand, if you really believe that they are children of God, and that they are not that much below you, because you also are a child of God, then when you are with them, they will feel it. They will get your signal, and you will do something for them that goes beyond what the world calls teaching. You will have performed a moral act that will last a lifetime and into eternity.

There is another thing that President Lee was going to talk about. I was absolutely entranced by a part of the manuscript I read that he never reached because he ran out of time. So I need to do this very carefully because he may want to use that part sometime. In fact, I encourage him to use it sometime. The nature of it is personal enough that I must do this carefully. He issued a rebuke, with authority, as skillfully as I have seen it done. I believe, President Lee, that you were inspired not to have time to include it. If the first thing I said about how to correct people is true, then you will probably want to do that masterful teaching in a private setting. What he planned to do was this.

Apparently something was written in the student newspaper that took a position. I understand it said something along the line that it is a higher moral standard to let other students make their own choices without interference, including breaking the rules of the university. President Lee’s comments, which he planned to make, had a happy tone. Always give a rebuke with a smile when you can. This one was jolly. He said something to the effect: “We really believe in free speech, and one of the benefits of free speech is that others will speak freely to you. And so they expressed an opinion, and I will now give you mine.” He did it in the nicest way. But it wasn’t just the manner, it was the content. He said in essence: “Let’s take your argument and see where it leads. Let’s consider the position you took and see what it would lead people to do.” He then piled example upon example of how it would lead to things that surely the writer would see as terrible. Then, rather than saying “aha” or “gotcha,” he ended by saying essentially, “Well, the responsibility you must take for the likely results of your position is something you would want to consider very seriously.”

One of the things that you and I exert is authority. In that moment I thought the president was planning to send, and perhaps will in private, the most wonderful signal. It is a signal that has been used on me over and over again, and it has blessed my life. The signal that he planned was really a simple one. It was that you can trust most people who have the right to the Holy Ghost. You can point out to them the results of their behavior, at least the likely results of their behavior, and then you can gently say, “You really are responsible.” Then, they will likely correct themselves.

The theme for this conference is, “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty” (2 Corinthians 3:17). In an interesting paradox, I would say, “And where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is real authority,” because if you believe enough, and communicate that belief, the Holy Spirit will rebuke better than you could with all your human authority.

I have lived in some fairly dictatorial situations, and yet I have not felt oppressed. I was once in a situation where I was invited to join a coup in an academic situation. Other people, who were working in the same situation I was, decided that they had had enough of what they saw as a dictator. They wanted me to help him get ousted. I remember getting the phone call and being absolutely stunned because oppression had never occurred to me. I told the caller that I was not interested in the coup. I literally did not feel oppressed. And I tried to figure out why.

I will tell you what I learned about myself and about you. Somebody, somewhere along the line, must have trusted me and said: “Look, Hal, I will exert my authority upon you this way. I believe in you. I believe that God can correct you, so I will point out the consequences of your behavior and then not push you very hard.” As a result, I have always felt free, even when some people tried to push me.

I believe not so much in the perfection of my bosses or my critics as I believe that I am still a child with lots to learn. Most folks can teach me something. No one can really take away the freedom that matters to me, and most criticism from human beings awakens an echo of a rebuke I’ve already felt from the Holy Ghost.

You can turn out students who spend their lives rebelling at authority. Many universities do. The riot police in most major cities in the world spend their time near universities for good reasons. But you could help students as your great president was going to do, and now will probably do in some private setting, by saying: “I believe in you. I believe in you enough to give you a different opinion. Here it is. Look at the implications of your opinion. You are responsible for your opinion and I am responsible for mine. And I believe that you can receive correction from the Holy Ghost. Ask for it.” The person may not agree, but, oh, what you will have told them about themselves, and about authority, and about the gift of the Holy Ghost. When someone does it that way to you, what a compliment they have paid you.

President Lee talked about one other thing. He said: “This board decision (he is now speaking about the nature of the university) means that we will continue to place our faculty recruiting emphasis on people who understand what it takes to give our students the very best possible education . . . people who not only have intellectual capacity and curiosity, but are also willing to work hard and use that capacity to its maximum potential. In short, the board understands the direction in which we have been going for the past couple of decades and has approved both the direction and the momentum.

“We intend to take full advantage of that momentum as we replace the unusually large number of retiring faculty members over the remainder of this decade” (President Rex E. Lee, Annual University Conference Address, August 26, 1991).

Now, let me tell you the little I know about how you make universities better places to get an education. I had the blessing of being invited to join the faculty at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. For many years it had been thought of as a nice graduate school of business, but Harvard and some others were the stars. At that time, the faculty made a decision to make their school as good as any other business school in the world. They got the financial resources together. They got Dean Arbuckle, who hired me. I came in the first wave of hiring. He hired others. I will name names: Jerry Sharp, who has won the Nobel Prize in economics; Lee Bach, who had been the founding dean of the Management School at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, which pioneered the use of mathematical techniques in business; Hall Leavitt, who had been at Chicago and MIT; and others you might not know. They were stars in the world of business schools.

I watched the results. I don’t know if you believe the rankings, but we got ranked number one just after I left. But something happened quite apart from rankings. We got better students, but we also provided them a better education. That came only partly because we hired stars.

To those of you who are here I urge: Don’t wait for the new arrivals. What happened at Stanford occurred, I believe, because the stars, when they came, found a solid core of real teachers. Let me describe them to you. By the way, this is my answer to the question of how research and teaching relate. My answer is that there are all kinds of teaching and there are all kinds of research, and the best of both have the same process at their centers.

Students, when they learn, have an experience like discovery. It can be frightening to them. To them, that first course in a subject is an unknown continent, strange and frightening and threatening, because not only is it hard to learn, but exploring it may convince them that they can’t learn. It may tell them something about themselves that can devastate them. The teachers who will make the difference are the ones who somehow can enter into that world with the student and feel what they feel, know what they fear, care about their fear, and help them move through the fear to learning. Research, of the right kind, can take a teacher into a world like the one a student must enter.

I will say something that could offend, but I will run that risk. I know how hiring gets done in some places where I have been. Although we always tried to look for broad criteria, we counted the number of published papers. Then we looked at the number of published citations a paper got in other people’s work to see who was paying attention. We looked at the quality of the journal it was published in and how tough the referees were. We, and you, might not admit we were doing it mathematically, but we added it up to decide who were the best researchers.

We had some great researchers by those standards at Stanford. Some were great teachers and some were not. I think we were blessed that the ones who saw research wholly or largely as a private enterprise left. They went to more congenial places. The ones who stayed to bless students saw their research not as a path to fame, but as exploration. Many of them didn’t keep writing the same paper three different ways with different data. They tried new things. Some of them even tried understanding what it was like to be a student. They cared about studying their own experience in research to find how to help students experience learning.

Rarely was the research they were doing something that went directly into the classroom, even at the graduate level. The kinds of things they were publishing did not generally go directly into the curriculum. I have heard the argument made that faculty research will bring the newest ideas to the students. That is rarely so at the undergraduate level. But a teacher who sees research as learning can come to care more about how students learn.

Again let me tell you one more story about dad. This last year my son Matthew was a student in a course on creativity at another university. He said, “Dad, I need an example of something creative.” I scratched my head and said, “Well, I think I remember that as your grandfather (that is my father) was dying, he kept talking to me about a new way to teach introductory calculus.” He was by that time not very well. He was excited about this new way to learn calculus.” I said to Matthew: “Maybe if you asked some of the people who worked with him, you would find something about it. Then you could use that as an example of creativity in teaching.”

Matthew, who idolizes grandpa, dug around and, sure enough, found a written record in dad’s papers. He was so excited. He said, “Well, now what do I do with it?” I said: “I don’t know. What do you want to do?” He said, “If I am going to write a paper about this creative thing of Grandpa’s, I had better find out what a mathematician thinks of it.”

Matthew made an appointment with a professor of mathematics. The professor first would not see him; then he didn’t want to read the paper. Finally Matthew persuaded him to read the paper. The professor responded that it was trivial. Only those who have been in mathematics would know that trivial is a real cut. It is almost better to be wrong than to be trivial. Matthew, who is not very experienced in cutting techniques, likely did not know that the professor’s intent was to crush him. But the professor succeeded: Matthew wrote a paper on something else.

Let me tell you the lesson in that story about creativity, research, and teaching. I don’t know how many papers Dad turned out, hundreds perhaps, that were published in the most distinguished journals. If you had hired him for that reason at this university, you would have been mistaken. His reputation would have given you some help. You would have had a famous chemist, but you would have hired him for the wrong reason.

Think of what Professor Eyring was doing with his precious time. Dad was not an amateur mathematician. He knew mathematics. And so, surely he knew that his approach to teaching calculus was not completely novel. My guess is he was open enough and garrulous enough that he probably tried it out on some mathematics professors, probably including the one who would have told him it was “trivial.”

Dad’s blessed weakness was that he didn’t know failure when it was labeled for him. Isn’t that interesting that he was still talking about it as he was dying. “Maybe if I just go back to that one more time. Maybe if I just get on another side of the question, I will see it.” Could he ever have published it? No. Feeling like a little child, and being sympathetic to students, he was trying to understand a way to help them. That’s the distinguished researcher you’d hire, but find you’d hired a teacher.

That answers for me the question of how teaching best relates to research. I would suggest to you that you take a chance this year. Some of you are wonderful researchers. I don’t want to tell you about your research programs, but I will simply say this: Look at how to present material in a way a young person can understand it better. Try to understand better how young people feel or think. Or perhaps just look at a different problem in your own research. Do whatever will make you feel what they feel, as if they were little children, as they try to learn.

“Behold, ye are little children and ye cannot bear all things now; ye must grow in grace and in the knowledge of the truth” (Doctrine and Covenants 50:40).

If your research makes you feel very, very bright or very, very good, or very, very famous, or very, very valuable, that could get in your way as a teacher. If, on the other hand, your research makes you feel very, very vulnerable, very, very anxious to know more, and if you read other people’s papers as often as you read your own, if you thrill when someone else gets an idea that makes yours look a little less important or even wrong, if all this seems like a wonderful game to you, then think how you can bless your students.

If you are someone who doesn’t do much research or hasn’t done much, don’t despair. Anything that you do that makes you feel like a learner, a little frightened but eager to try, and where you can feel the hand of God on you saying, “Don’t worry, you can be like me someday”—think what that can do for your teaching. I can’t tell you what kind of research or writing or creative work to do, but I can tell you the blessing it can be to our students when it helps you understand how they really feel, how they really fear, how they really struggle, how they wonder what limits there are on what they can become.

There is a little risk in closing in the way I now intend to do, because I don’t want to suggest that what you do and I do approaches what the Savior did. But we can still learn from him. Listen, from Alma:

“And he shall go forth, suffering pains and afflictions and temptations of every kind; and this that the word might be fulfilled which saith he will take upon him the pains and the sicknesses of his people.

“And he will take upon him death, that he may loose the bands of death which bind his people; and he will take upon him their infirmities, that his bowels may be filled with mercy, according to the flesh, that he may know according to the flesh how to succor his people according to their infirmities” (Alma 7:11–12).

If you can feel what it is like to be a student and feel their pains and afflictions, you can make a great difference, a moral difference, in how they feel about who they really are and what they can become.

Testimony

I bear you my testimony that God lives. He is our Father. Every student of yours, every student of mine, is equally, with us, a child of God. God has promised that all can be like him if we can do some things a child can do. I don’t know how that will work in the spirit world in terms of chemistry, mathematics, botany, or whatever we try to teach. I don’t know whether it is possible to skip over the hard work that you and I have done. I doubt it. But the people who stop trying to learn because they believe they are incapable are wrong. They, and we, can learn all truth. Be careful what signal you give about where you think the limits are on anyone, including yourself.

I bear you my testimony that Jesus is the Christ. He understands us. That I know. In this room tonight are people, as there will be in every class you ever teach, who are struggling. Someone here has a dying parent or a dying child. Someone here has a health problem. Someone here is in financial difficulty. Someone here has some other difficulties that I don’t know anything about nor could I relieve. But God knows. He not only knows, but Jesus the Christ has felt your infirmities. I pray that you may know that. Think of that when you teach. Perhaps the most important thing you can know is that you are a child of God and that he provided you a Savior. The Savior, in addition to paying the price of all our sins, suffered enough to understand all our pains and all our fears.

I bear you my testimony that Ezra Taft Benson is a prophet of God. I bear you my testimony that he loves us. If I should not meet with him again, the last incident I will remember is his hand on mine, reaching out to thank me for holding a door. He noticed me. He felt for me. He understood me. I think that is a gift of God, not available only to a prophet but to all of God’s children who exercise their faith to receive the gift of the Holy Ghost.

I am grateful for you. I pray that you may feel God’s gratitude and his confidence as you go to teach his children who someday can be like him. Of this I testify in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

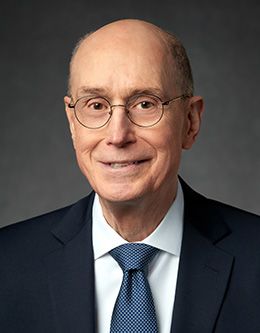

Henry B. Eyring was First Counselor in the Presiding Bishopric of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this address was delivered during the BYU Annual University Conference held 27 August 1991.