“You will find that he knew the way and wanted to share it with you. And you will have confirmed to you that he was the perfect example in mentoring, as he is in all service that brings real value.”

Such a fall faculty meeting as this brings back pleasant memories of the excitement, laced with a little apprehension, of being a fresh faculty recruit. My heart goes out to the nearly 100 newcomers, with some sympathy for your mild anxiety, but far more with an enthusiastic welcome. We are delighted by your choice to join us.

This university has a formal system to assure that you will have at least one mentor. But if you reflect on your lifetime in education, those mentors with the greatest impact on your growth seemed more to have been in that relationship with you by choice than by assignment. And, at least for most of us, there is a feeling of warmth that comes from simply remembering the experience of being guided by such a master. I don’t have the data to test it, but my hunch is that those of us who have chosen a university faculty career have had more in quality and quantity of those relationships than our classmates—even those equally gifted—who did not choose this vocation.

If I could use only one process to illustrate what goes on in academic life, from the time of Plato until now and beyond, I would pick mentoring. And my practical reason for talking about it today is that I believe the influence of informal mentors and mentoring may be more important to the future of the individual faculty member, and thus to this university, than any administrative thing we may do. So, my hope is that by sharing what I know about that process I might make it work better. Even if I don’t, I will at least have put my lever on the right fulcrum.

I realize that more than a few of the newcomers, as well as the veterans, may see little need for a mentor. You may even feel that you have had mentors enough, that now is the time to break free from the obligations you felt such relationships placed upon you as a graduate student or perhaps as a junior faculty member. Let me urge you to reconsider for at least two reasons.

In the first place, it seems to me that almost all of us have mentors, whether we recognize it or not, as long as we are growing intellectually. As we move along in our careers, they may not be near us, or they may not even be available to us in the flesh, but there seems to be a natural need to reach out to someone as a trusted counselor, even if only from memory or from a book. To me the question is not whether we will have mentors but which ones we will choose. In the second place, then, if I am right that we seem bound to have a mentor or mentors, why not make the choice consciously and well?

I can make my suggestions best by telling of one day in my life. I have chosen it as an example not because it is representative, but because it has been instructive to me, teaching me something about how to choose a mentor and what it takes to keep one. And, as is so often the case, what went wrong is as least as illuminating as what went right.

The memory is of an afternoon in an office at the RAND Corporation. It must have been in the afternoon. I remember facing the west window. The man sitting before me had his back to it. As the talk went on, he came more into silhouette against the sun setting into the Pacific Ocean.

Just the other day I looked up at that window from the pier in Santa Monica. I thought of repeated rhythms in our lives because I was walking along the cliffs and then to the pier with my son, Henry, who had flown in that morning from Tokyo. He’d scheduled his flights so that we might connect for a few hours to talk about his life and his work. How like him I was in the interview at RAND so long ago.

I had been a professor for a year. My efforts to move some research to publication had stalled as I met the challenge of my first year of teaching. But RAND gathered people that summer to work on problems like the ones I was studying. And so I was invited. Even with my full attention during the summer, the work not only was slow but seemed to me confused, to lack direction. I began to doubt that my research question was even phrased in a way that could lead me to anything that would matter to anybody.

And so a kind department head offered me the chance to talk with Herbert Simon. Professor Simon was another of the people there that summer. You would have had to have worked in that field in that faraway time to know what such an invitation meant. No one had done more than he had to change the way all of us thought about how decisions are shaped in organizations. He had not yet won the Nobel Prize in economics. In fact, I’m not sure there was such a prize yet. But I knew what an opportunity I was being offered. I could scarcely believe my good fortune.

I prepared hard for that meeting. I struggled to assemble all of my work, to make some order, some sense out of it. I knew that the chance to have such priceless counsel might come only once.

And yet I hoped for more, something that would last longer. So, I thought deeply about what questions to ask, what counsel to seek. I had no idea whether he would give me more than a few minutes, whether he would even read what I would send to him, or why he had agreed to see me. I wish I had known then what I know now about why such an interview occurs and why we sometimes win and keep a mentor.

I went to that meeting having decided that I would take his counsel. Had you seen into my heart, you might have called me credulous. But I had been humbled by my experiences. And I believed that he knew more about my problem than I did, perhaps more than anyone else in the world. And so I went trusting, ready to take counsel.

I found that he had read my work, carefully and critically. It was clear at the outset that he had been pondering my problem. The few questions he asked cut deep, revealing the weaknesses in what I had done. He obviously felt that helping me with my problem was going to be more important than making me comfortable. He seemed to assume that I cared more about my work than my ego.

And yet, forthright and candid as he was, he was not my adversary nor my rival. He listened with great kindness, with what felt almost like sympathy. He listened with complete absorption. It was as if there were no other person alive but me and no ideas in the world but mine. It is not too extreme, at least for me, to say that only my mother, my wife, and my other mentors have ever listened to me with such compassion. After what seemed an hour, he began to do the talking, quietly. I recognized the continuity, the steadiness in his counsel because it reflected what I had read of his publications. But he talked about my work, not his. He corrected not so much by pointing out mistakes as by showing me where to find opportunities to add value to my work.

He had obviously no intention of doing the work for me, or even telling me how to do it. He instead described where it might lead and what value it might have. He spent hours with me. And, at the end, he said words that gave the impression to me that he would continue to care about me and my work.

But we never met again. In fact, I doubt that he would remember that we met once. He and I were there through the summer and, on occasions, later. When I returned to Stanford I had a number of faculty colleagues who had worked with him at Carnegie Tech. All the conditions seemed present, as I look back, to extend that afternoon to a lasting relationship that could have been of great worth to me and to my work.

Let me piece together what I have learned about why I was right to choose to try to win such a mentor and yet why I did not. I’d boil down what to look for in identifying a great potential mentor to three characteristics. And he had them all. First, and surely most important, he had an understanding about the world I was trying to navigate. He didn’t just know facts about it; he had understanding about the world I was trying to navigate. He didn’t just know facts about it; he had a map, and a good one. And I know now what kind of a map matters most—it’s one that will show you where value will lie in the future. He didn’t just know decision theory and organizational theory; he had a sense of where the combination was going and what would be of most worth to the people working on that combination as we went. He had the capacity to say, “This contribution or that contribution will make the most difference.”

Now, you may object this way: “But all that I want in a mentor is someone who can tell me how to make continuing status at BYU or whether to accept this committee assignment or whether to keep my bike in my office.” But if that is your objection, then we agree: those are judgments about the future, and they have imbedded in them judgments about value. If those are the questions you want to ask a mentor, the future you care about is immediate and the benefits personal. But the principle is the same: a good mentor will guide you reliably toward future value for somebody. And for the future and the values I cared about then, Herb Simon would have been tough to beat.

Two other characteristics of a great mentor, which I could only know he had when I got into the interview, are common to all great mentors I have known: integrity and generosity. Those traits are not especially easy to find, nor are they often combined in the same person. You will meet people so tough-minded that the truth, justice, and probity matter more than what you want or even what they want. I’ve known a few such flinty people. But only rarely have I found those who have combined such integrity smoothly with a feeling toward you so generous that what is good for you will be good for them, almost as if your victories and your happiness were their own.

Now I don’t want too seem too pessimistic about finding such people, for I have known enough of them to fill a lifetime. But I sensed then, and you will be wise to recognize now, what a prize such a mentor can be.

Your own experience, with a little reflection, will tell you what I know about why such relationships endure—and why they do not. One word probably captures it: trust. You give it and you get it. The value a mentor has to you comes from your trust. Because I had such confidence in Professor Simon’s understanding, and because of his integrity and generosity so evident in that afternoon’s chat, I trusted him enough to subordinate myself to him. I conferred authority on him because I trusted him. I did not ask to be his peer. I was prepared to let his vision guide my hard work toward where he pointed to potential value. And giving him that trust was my choice to make.

Now, the mentor makes a choice, too. Herb Simon only had so many afternoons that summer. He gave me something of great value to him and to others. Everyone there wanted to see him, and he had work of his own to do. Given his generous nature, he was going to help people that summer, but he had to make choices about whom to help. He trusted me and my work enough to invest an afternoon. The return he hoped for was likely some combination of good in my life and perhaps some tiny boost to his own work. He must have seen in me some evidence that I would take his counsel, that I would work hard, and that something of value might come out of it.

Without being too modest, let me guess that he decided that his trust was better placed elsewhere. He must have seen the working papers I produced, albeit a little slowly, once they were circulated. He would have noticed that I began following his vision but later went in other directions. And as I look back over the years, his judgment has proven right: My work produced less value than that of those who searched where he pointed. I made my choices, they made their choices, and he made his choices.

All of this illustrates the great freedom in your relationship to a good mentor, at least as I have experienced it. You decide to grant the mentor authority by your trust. You choose to try to prolong the relationship. And you hold the power to end it. There are several ways to bring it to a close. It’s a good idea to recognize when you are doing it. Listing a few of the ways might help.

They all stem from your losing your trust in the mentor. You can make that obvious by following the mentor’s vision. Another way, and one you may not even notice yourself doing, is to show your waning trust by the way you confront the mentor. It’s not a clear line, but there is a region of challenge where you are choosing to end the relationship. Mentors are generous, and they like to help creative people. So they are used to some “pushing back” from those whom they counsel. But I will tell you one way to know when you have made a choice that is likely irreversible. It is a simple one: When you move from asking penetrating questions and suggesting tentative ideas to trying to change the mentor’s map, you have chosen to end the relationship. That may not be a tragedy in your view, but it is better to make it a conscious choice than to have it come as a surprise.

I did nothing so rash in that summer at RAND. The drift in my work away from his vision was gradual. But my guess is that the greater problem was that I was too cautious, too slow in sharing results. I polished and repolished my work before letting anyone see it.

If you want praise more than instruction, you may get neither. The mentors of most worth that I have known have a feeling of urgency in their own work that makes slow response from you seem a sign of disinterest. And this lack of interest looks a lot like lack of trust. So, if the mentor says he or she would be willing to talk about your work on Tuesday, my hard-won advice is to deliver something less than perfect early Monday. You will have suggestions back by Monday night, and you’ll carry with you another version, much improved, by Tuesday morning. Of course you won’t sleep much on those Monday nights, but you won’t have enough of such days and nights in a lifetime anyway. An you will have gone a long way toward keeping a mentor.

Now, all of this will explain both my appreciation for the mentoring that has gone on at this university and my optimism about its future. Mentoring goes best and makes the most difference when people realize that there are lots of questions about future value to be answered when they trust. Let me tell you, then, why I am so confident about how much your mentoring will matter here and how well it will be done.

Two happy circumstances have allowed me to do the homework that is the basis of my optimism. The first was the invitation to return, after a long absence, to be commissioner of the Church Educational System. The other opportunity was the gracious permission of President Lee to explore across this campus.

My return to the CES taught me again that it is easy to talk about exponential rates of change, but it is something else to navigate them. When I was first president of Ricks College, we worried about recruiting to get enough growth in student admissions to justify the faculty we had hired the year before. Six years later, when I came to the commissioner’s office, we were giving serious attention to the enrollment pressures at BYU and some thought to the day when Ricks College might face the same pressure. When I returned to the commissioner’s office from the Presiding Bishopric, I found that Ricks College had rejected as large a number of freshman applications as had BYU.

For years I had taught and talked about the prophecy in Daniel. I knew that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was the stone cut out of the mountain without hands. I knew that it would roll forth. And I knew that it would fill the earth. But the rumble had not been real enough to motivate action before it was upon me.

Just as the effects of the rate of growth were surprising, so was the accelerating geographic reach of the Church. Again, I knew we would go to every nation, kindred, tongue, and people. But I had not thought carefully enough to prepare for the effects: When I left to serve in the Bishopric, the Church was in slightly more than 70 nations. When I returned to education, seven years later, the Church was in more than 140 nations.

I cannot trace out all of the implications of these accelerating changes for the Church Educational System. But some are evident. I never go to a stake conference and President Lee never meets an alumni group without answering the question: What are we to do now that we can not reasonably expect that our children will attend a Church campus?” It is not asked out of curiosity. There is emotion, deep emotion. That emotion grows in intensity when you tell them that the campuses will not be expanded and that new campuses will not be added. The emotion is even higher when a mother calls to describe her daughter who has labored for years to qualify but has been denied admission. And often there seems to have been a neighbor child admitted, in the eyes of the mother, less qualified and certainly less devoted to the Church. Stake presidents tell me that where once five or six came here from their stakes, now only one or two come, and often not the ones they consider the most faithful. A father who graduated from BYU writes a polite letter describing the sorrow of his prepared son who cannot attend and asking us to please stop sending alumni correspondence to his home.

More and more of the letters pleading for admission will come from foreign lands where education is even less available. They are new members of the Church, full of faith, but with not enough income to pay for education there, let alone here, and without the resources to get adequate preparation. The gross national product per person in this country is 10 times what it is in the nations to which we will now go. Their tithes are small but cut even more deeply into their necessities than do ours. And yet almost none of them will ever see this campus—supported by the tithes of all the faithful—except in colored pictures.

We can already discern the path of the responses within the Church Educational System. In each case it is to seek answers to the question “As this resource we have been given charge for grows scarcer in relation to an exponentially growing demand, how is it prepared to give even greater value?” Here are some early answers.

Institutes of religion are located next to more than 2,000 campuses all across the world. The populations at some of those institutes are so large, with student stakes, that the religious and social experience for Latter-day Saint youth can equal the best that is found on our campuses. But some, too many, are small. I visited one near a major university in the western United States in the last few weeks where fewer than 10 Latter-day Saint freshmen will enroll in the school. When I talked with a mother whose daughter will attend, I was grateful I could describe the enhancement of institutes that is beginning.

We will expand the opportunities for studying the gospel, for meeting more young people, and for greater participation in Church units. The buildings and the dedicated institute faculty are in place because of the foresight of the Church Board of Education. And the certain growth of the Church will accelerate the enhancement of their power to bless. That vision cheers my heart as I visit faculty members working alone with small bands of students in institutes across the country who may have thought they’d never see the promised land of teaching unless they got transferred to Logan or Salt Lake. Now the promise is running in their direction.

Ricks College will respond to the admissions pressures caused by the growth of the Church and their enrollment limit in a way also made possible by its roots. Through years of change, from a tiny academy to a normal school to a four-year college and then back to its two-year program, there have been some constants. One has been in attitudes of the faculty. The faculty drawn there have, with only rare exceptions, put their whole hearts into the proposition that what a student has done in the past is no limit on the future. The open admissions character of Ricks College was not in the admission criteria nearly so much as it was in the hearts of the faculty. It is hard to see just how they will do it, but even as a smaller and smaller fraction of the Church can attend Ricks College, it will find a way to admit students in whom other faculties might not see the potential.

BYU–Hawaii was founded on visions of its future. Some of you know the accounts better than I, but I have felt their effects. President McKay foresaw students from many cultures and countries drawn together in love and learning. There they were to discover how to study and live in unity, as the Lord’s people will be doing when he comes again. Some of you have served there. You have felt the direction and seen where it is leading. So have I, each time I have walked and listened and taught there. The reality is not yet what President McKay saw, but it will be. And its realization will add great value to its students, to the Church, and to all of education in an expanding Church that will become more unified and in a shrinking world that seems to be splintering.

Now, let me tell you why my visits across this campus with you have given me such confidence that BYU will find its way to contribute to the lives of people across the world who cannot come but whose affection we must not lose. I found three pleasant surprises. They will not surprise those who know the whole campus, but they may be less obvious to our newcomers and to those who must rely on second- or third- hand reports and newspapers.

The first surprise was to discover the brilliance, the good judgment, and the understanding of the faculty. Gifted and devoted scholars have chosen to come here in increasing numbers. As I visit with them, I am struck by the depth of their discernment about what is happening in their disciplines, in the Church, and in the world.

And the second surprise for me was the rate at which their fields are changing and the degree to which, with all the demands on their time, they contributed to that development. You have to visit with professors from nursing, physics, and then linguistics to be struck by the diversity of scholarly approaches and methods—but there is one prominent commonality: change is occurring so rapidly in disciplines that the edges are blurring and the very value assumptions on which they rest are being reexamined.

The great educational questions have always been more about value than facts. “Shall we require Latin for final honors?” “What about requiring plane geometry?” “What must the educated person read and why?” We are used to asking such questions about relative value and taking our time to answer them. But they are being raised in every field, with greater frequency and with emotional intensity and deep divisions. That rate of change creates great opportunities for growth when we have mentors with reliable maps of future value—and we have them here.

My third surprise was the widespread agreement we share on what future values will matter most and to whom. One illustration of that trust is the reaction to the proposition that our greatest value will be contributed by putting primary emphasis on undergraduate education. Now that is not an altogether obvious choice for a faculty charged to forge a great university. Whether people really trust such an assertion about the future is better measured by what they risk than by what they say. Across the university I have found world-class scholars who have put undergraduates first, and that is to me a remarkable proof of shared trust in a vision of value.

One anecdote involved two undergraduates I’ve met. One of our professors allowed them to present to a meeting the research in which they participated. A professor from another university asked, “Where did you get those post-docs?”

“They aren’t post-docs.”

“Well, then, where did you get such graduate students?”

I won’t finish to the punch line. That level of trust in the primacy of undergraduate education being a path to a great university, not an impediment, reaches into departments across the campus.

More evidence of that was the success of our undergraduates in the national Putnam Mathematics Competition. Of 2,400 who competed, one BYU student was 98th, one 102nd, one 122nd, one 234th, and one 351st. By coincidence, both Cal Tech and Berkeley matched that record. Nevertheless, that our students did so well is not coincidental but rather a result of distinguished scholars caring enough about teaching undergraduates to do it very well. What surprised me about this, and other evidence I found, was how enthusiastically the majority of us are working toward shared visions of what matters. Even where we differ, and I found sharp differences, the differences are more often about means and timing than about ends. Those differences are serious, but few universities even hope for the breadth of consensus we have about what will ultimately matter and to whom.

Now you can see why I am so sure that mentoring will work here, and work well. There are gifted mentors aplenty. There are clear and shared maps of where future value will lie. And there is widespread trust in mentoring.

Those who have taught here have always had unique mentors. Dr. Maeser had at least one we know about: a prophet named Brigham Young. Other teachers have followed and other prophets, widely different in background and personality and serving amidst vastly different conditions. Yet with all that change, there is constancy, a steadiness, in the map they have shared of future value.

You remember some of the words. First, those of John Taylor: “You will see the day that Zion will be as far ahead of the outside world in everything pertaining to learning of every kind as we are today in regard to religious matters” (The Gospel Kingdom, p. 275).

Then, of David O. McKay:

In making religion its paramount objective, the university touches the very heart of all true progress. By so doing I declare with Ruskin that “Anything that makes religion a second object makes it no object. He who offers to God a second place offers Him no place.” It believes that “by living according to the rules of religion a man becomes the wisest, the best, and the happiest creature that he is capable of being.” [The Church University, October 1937]

And, then, of Spencer W. Kimball:

As previous First Presidencies have said, and we say again to you, we expect (we do not simply hope) that Brigham Young University will “become a leader among the great universities of the world.” To that expectation I would add, “Become a unique university in all of the world!” [“The Second Century of Brigham Young University” (10 October 1975), in Speeches of the Year, 1975 (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), pp. 256-257]

One way in which this university is unique is in its power for wise mentoring. I would say to a the new faculty: Take responsibility for your futures here with confidence. There are more mentors available to you here who have understanding of where real value will lie and who blend integrity and generosity without diluting either than you will find elsewhere in any one place. You know how to identify them. You know how to win their trust, and you know how to keep it. Because of that, I have confidence in your future and in that of the university.

Now, the map of the future will only become perfectly clear as we work our way into the territory it describes. But one crucial part is clear to me: In some not very distant time you and I will meet the Savior, at a place where he employs no servant. I cannot picture the details, but you will feel as if you are alone with him, and you will have his full attention. You will then know what you could know now, that he has reached out to you, directly and through servants, some who were volunteers and some called, but all of whom you chose or rejected as your trusted counselors. You will find that he knew the way and wanted to share it with you. And you will have confirmed to you that he was the perfect example in mentoring, as he is in all service that brings real value.

This is how one who knew him described him, and the relationship we could have with him, if we choose it: “Wherefore, brethren, seek not to counsel the Lord, but to take counsel from his hand. For behold, ye yourselves know that he counseleth in wisdom, and in justice, and in great mercy, over all his works” (Jacob 4:10).

I testify that this university is one of this works—and that he counsels over it—in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Brigham Young University. All rights reserved.

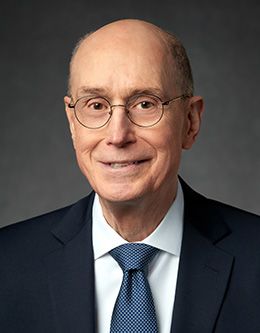

Henry B. Eyring was a member of the Quorum of the Seventy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this address was delivered at the BYU Annual University Conference on 26 August 1993.