Trust and accountability are two great words by which we must guide our lives if we are to live beyond ourselves and rise to higher planes of service.

I cannot understand how I agreed to come here today. We have just concluded a general conference of the Church and a number of associated meetings. I am hoarse from speaking and feel drained of things to speak about.

On Thursday, day after tomorrow, I leave for London for a regional conference to be followed by the rededication of the London Temple and then the rededication of the Swiss Temple. There will be dedicatory prayers and many talks to be given in the numerous dedicatory sessions that will be held.

How did I ever agree to come here today? I ask myself. Do you have the same problem that I have? Someone asks you to do something far in advance, and you agree without really thinking of what that will entail. Then, when the day is upon you, you doubt your capacity, you worry, you ask why you ever agreed, and you pray for inspiration and enlightenment to fulfill your commitment.

I guess we all have such experiences. We hope they turn out well.

I am reminded of an incident of a long time ago when a friend came to see me. He was to be married in the temple in two days. He had been going with his fiancée for many months. She was a wonderful girl—beautiful and able. He had proposed. She had accepted. And they had set the wedding date. All went wonderfully until a few days before when he began to think of how long eternity is. For some unexplainable reason, he began to doubt and to wonder. He came to me frantic with worry.

I said to him, “Come on, Jim. You have known Mary for three years. This has been no sudden courtship. She is a wonderful girl. You know it, and I know it. Put your doubts out of your mind. Trust in the Lord, and trust in her. Think in terms of what a wonderful thing it will be to share your life with her through all the years to come. You have been looking on the dark side. Look on the bright side. If you will keep sacred the bond of trust between you, you will make it, and you will make it in a wonderful way. You will love it and wonder why you ever doubted.”

I am happy to report that they recently celebrated their fifty-fourth wedding anniversary. They have reared an excellent family. Theirs has been a wonderful marriage. And now in their golden years, they love and cherish one another, even more than when they were young.

And so, I come to you this morning looking on the bright side. I hope and pray that I may be inspired to say something of interest to you, something that will be helpful.

I am here representing the First Presidency of the Church and the Brigham Young University Board of Trustees. President Benson serves as chair of this board, and his counselors serve as vice chairs.

It has been customary for the chair to speak here each October shortly after the opening of the fall semester. President Benson is unable to come because of his advanced age. We all regret that. I do particularly. I think he would love to be here, and I would love to have him here. I bring you his love and his blessing.

I likewise bring the respect and appreciation of the entire board. I speak to both students and faculty in doing so.

First, I want to thank you for the strength of your desire to teach and learn with inspiration and knowledge, and for your commitment to live the standards of the gospel of Jesus Christ, for your integrity and your innate goodness. I am confident that never in the history of this institution has there been a faculty better qualified professionally nor one more loyal and dedicated to the standards of its sponsoring institution. Likewise, I am satisfied that there has never been a student body better equipped to learn at the feet of this excellent faculty, nor one more prayerful and decent in attitude and action.

There may be exceptions. There doubtless are. But they are few in number compared with the larger body.

I do not want to infer that this is paradise on earth. You may think it just the opposite as you grind away at your studies. But notwithstanding the rigors of that grind, the unrelenting day-after-day pressure you feel, this is a great time to be alive, and this is a wonderful place to be.

This institution is unique. It is remarkable. It is a continuing experiment on a great premise that a large and complex university can be first class academically while nurturing an environment of faith in God and the practice of Christian principles. You are testing whether academic excellence and belief in the Divine can walk hand in hand. And the wonderful thing is that you are succeeding in showing that this is possible—not only that it is possible, but that it is desirable, and that the products of this effort show in your lives qualities not otherwise attainable.

As you are aware, we recently announced in conference that another temple will be built in this general area. The reason is that the Provo Temple is the busiest in the Church, operating beyond its designed capacity. The Jordan River Temple is the second busiest in the Church. One factor in all of this is the devotion to temple work of Brigham Young University faculty and students. Many of you, I am told, attend a session in the temple early in the morning before your classes. Many are there in the evening and on Saturday. This all says something of tremendous significance. It speaks of devotion and loyalty, of unselfishness and faith.

Furthermore, this remarkable faculty carry many responsibilities of great importance in the Church at the general level, at the stake level, and at the ward level. You are men and women of faith as well as of learning. I believe you are the equivalent of your peers anywhere in the world in terms of professional qualifications. Beyond this, you speak with conviction concerning the God of Heaven, the Savior and the Redeemer of the World, and the beauty and power of the restored and eternal gospel. I believe you seek to live these principles. I know of no other university faculty—I think there is none other anywhere on earth—where the members can stand and say with conviction, “We believe in being honest, true, chaste, benevolent, virtuous, and in doing good to all men” (Articles of Faith 1:13).

I believe that you seek to exemplify that declaration in your lives. I commend you and thank you and extend to you our appreciation and respect.

I repeat, there may be exceptions. But I think those are few. And if such there be, I am confident that in their hearts they feel ill at ease and uncomfortable, for there can never be peace nor comfort in any element of disloyalty. Wherever there is such an attitude there is a nagging within the heart that says, “I am not being honest in accepting the consecrated tithing funds of the humble and faithful of this Church. I am not being honest with myself or others as a member of this faculty while teaching or engaging in anything that weakens the faith and undermines the integrity of those who come to this institution at great sacrifice and with great expectations.”

I recently read a book that fascinated me. It is a dual biography of the two great generals of the American Civil War—Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant. They were personalities as different as perhaps two men could be. One was the epitome of intellect, rigid self-discipline, culture, and rectitude. The other was somewhat careless in his ways, his career marked with failure, but he possessed a shrewd and calculating mind. Each in his own way was brilliant.

Moreover, each was driven by a great and serious sense of trust imposed by those to whom he was accountable. One had greater resources and, I believe, perhaps a better cause than the other, and this accounted for his victory. But the other was nonetheless a great and remarkable man. I could spend the hour here talking about each of them. But that is not why I am here. I mention them only because the author of this book, after tremendous research, concluded: “Trust is what makes any army work, and trust comes from the top down” (Gene Smith, author of Lee and Grant: A Dual Biography, quoted in “Hitching a Ride to History,” in Reader’s Digest Condensed Books, vol. 4 [Pleasantville, New York: Reader’s Digest Association, 1984], p. 299).

I want all of you to know that you have the trust and confidence of the governing board. This is called the board of trustees. It also carries a very heavy and sacred trust. It has the burden of responsibility for setting policies of governance for this great institution and responsibility for the expenditure of the many millions of dollars of sacred funds used to maintain this university.

We share your exuberant gladness when BYU wins a well-fought game. We share your pride when BYU and members of its faculty or student body are honored by its peer institutions and people. We share your pain and your hurt when the media exploit, as they are wont to do, any untoward, any unseemly, any ugly or misguided statement or act emanating from faculty or students. You are part of this great family we call The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. When one member experiences a significant accomplishment, the others rejoice with him. But when a member does something that is a violation of the code of that family, the entire family is injured and feels the pain.

Every one of us who is here has accepted a sacred and compelling trust. With that trust, there must be accountability. That trust involves standards of behavior as well as standards of academic excellence. For each of us it carries with it a larger interest than our own interest. It carries with it the interest of the university, and the interest of the Church, which must be the interest of each and all of us.

Some few students resent the fact that the board has imposed a code of honor and a code of dress and behavior to which all are expected to subscribe. Bishops, and now stake presidents, are requested to interview each student and certify his or her acceptance of the standards set forth in these codes.

I think I can hear a student, perhaps a number of them, saying to a bishop, “Why do we have to sign these codes? Don’t they trust us?”

I am reminded of what I heard from a man—a great, strong, and wise man—who served in the presidency of this Church years ago. His daughter was going out on a date, and her father said to her, “Be careful. Be careful of how you act and what you say.”

She replied, “Daddy, don’t you trust me?”

He responded, “I don’t entirely trust myself. One never gets too old nor too high in the Church that the adversary gives up on him.”

And so, my friends, we ask you to subscribe to these codes and to have the endorsement of your respective bishops and stake presidents in doing so. It is not that we do not trust you. But we feel that you need reminding of the elements of your contract with those responsible for this institution and that you may be the stronger in observing that trust because of the commitment you have made. With every trust there must be accountability, and this is a reminder of that accountability.

It is so with the faculty and with all of us. We ask that all members of the faculty, who are members of the Church, be what we speak of as “temple-recommend worthy.” This does not evidence any lack of trust. It simply represents a standard, a benchmark of belief and action. The setting of this standard is not new or unusual. It is not new at BYU or in the Church Educational System, though it has been unevenly applied at times. It is a standard applied widely in the Church.

Our thousands of bishops, who stand as common judges in Israel, annually must renew their own temple recommends, as must stake presidents also. The renewal of that recommend becomes a renewal of commitment. We live in a world and in an environment where we are surrounded by the corrosive and erosive elements of the world. We are all human, even though our callings be high and noble. We all need the constant reminder of commitments we have made and standards to which we have subscribed.

Surely, our Father in Heaven loves his sons and daughters. He trusts us. That very trust becomes as an iron rod to which we may cling as we walk the path of immortality. Some stumble and err and violate the trust. They are accountable for what they do.

I am confident the Savior trusts us, and yet he asks that we renew our covenants with him frequently and before one another by partaking of the sacrament, the emblems of his suffering in our behalf.

We are, of course, properly concerned about you who teach at this great institution. You are the bone and sinew of the university. We are concerned that your academic credentials be the very best and that there be a quality of excellence in all you do. We are also concerned with your faith, your principles. I hope you will not regard us as being unduly cautious or unnecessarily critical. We act in the spirit spoken of by Alma concerning teachers in his day. Said he: “Trust no one to be your teacher . . . , except he be a man of God, walking in his ways and keeping his commandments” (Mosiah 23:14).

Yesterday, much of the world celebrated the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ voyage of discovery. Scholars may dispute certain aspects concerning the priority and outcomes of that historic venture, but none can ever sell short the man who kept his trust in God as he sailed the trackless sea and who held himself accountable to the sovereigns of Spain, who were his sponsors.

As a boy I read Joaquin Miller’s poem “Columbus” and was stirred by it. I recall a few of those lines:

Behind him lay the gray Azores,

Behind the Gates of Hercules;

Before him not the ghost of shores;

Before him only shoreless seas.

The good mate said: “Now must we pray,

For lo! the very stars are gone,

Brave Adm’r’l speak; what shall I say?”

“Why, say: ‘Sail on! sail on! and on!’”

. . .

Then pale and worn, he paced his deck,

And peered through darkness. Ah, that night

Of all dark nights! And then a speck—

A light! A light! At last a light!

It grew, a starlit flag unfurled!

It grew to be Time’s burst of dawn.

He gained a world; he gave that world

Its grandest lesson: “On! sail on!”

Columbus kept his trust and discovered a hemisphere.

I think of Lord Nelson on the morning of the Battle of Trafalgar when he said: “England expects every man will do his duty.” After that fierce and bloody contest, as he stood on the deck of his ship to extend humanity to his enemy, a ball was fired within fifteen yards of where he stood.

He fell to the deck, his spine shattered. He expired three and a quarter hours later, his last articulated words being, “Thank God, I have done my duty” (21 October 1805, from Robert Southey, Life of Nelson [1813], ch. 9).

A tall shaft and statue stand in his honor in Trafalgar Square in London.

Wilford Woodruff, in 1835, not long after he had joined the Church, was sent on a mission with a companion who was to accompany him. They traveled through mud and floods, experiencing a great variety of hardships in the pursuit of their duty. He wrote in his journal:

We walked forty miles in a day through mud and water knee-deep.

On the 24th of March, after traveling some ten miles through mud, I was taken lame with a sharp pain in my knee. I sat down on a log.

My companion, who was anxious to get to his home in Kirtland, left me sitting in an alligator swamp. I did not see him again for two years. I knelt down in the mud and prayed, and the Lord healed me, and I went on my way rejoicing. [Leaves from My Journal (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1881), p. 16]

Wilford Woodruff kept his trust and lived to become a prophet.

I repeat the quotation I gave earlier: “Trust is what makes any army work, and trust comes from the top down.”

Trust is what makes a government work, and maybe a lack of trust is one reason for the serious problems we are experiencing. Trust is what makes the wheels of commerce turn. It is what makes possible the strength and growth of the Church. It is what makes Brigham Young University work.

Trust and accountability are two great words by which we must guide our lives if we are to live beyond ourselves and rise to higher planes of service.

This is, and must ever be, an institution where the soul is nurtured while the intellect is trained.

The motto of this university came from the pen of a prophet of God who spoke under the power of revelation: “The glory of God is intelligence, or, in other words, light and truth” (D&C 93:36).

The charter of its conduct was spoken by another prophet to its founding president: “You ought not to teach even the alphabet or the multiplication tables without the Spirit of God” (Brigham Young to Karl G. Maeser, quoted in Alma P. Burton, Karl G. Maeser: Mormon Educator [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1953], p. 26).

Among the marvelous words of the first section of the Doctrine and Covenants are these:

The weak things of the world shall come forth and break down the mighty and strong ones, that man should not counsel his fellow man, neither trust in the arm of flesh—

But that every man might speak in the name of God the Lord, even the Savior of the world. [D&C 1:19–20]

We trust you to do so. We love you. We respect you. We pray for you as faculty and students. We place upon you a great and sacred charge to excel in the imparting and learning of secular knowledge and at the same time nurture the spirit within. I challenge you to stand always on a high plane of moral integrity, of spiritual strength, of professional excellence.

This is a world-class university, a great temple of learning where a highly qualified faculty instruct a large and eager body of students. These teachers impart with skill and dedication the accumulated secular knowledge of the centuries while also building faith in the eternal verities that are the foundation of civilization.

Such is our unqualified expectation. Such, I sincerely believe, is the desire of all, save perhaps a few. Such, I sincerely hope, will be the resolve of everyone.

May God bless you, my beloved associates, both young and old, in this great undertaking of teaching and learning, of trust and accountability, I humbly pray, in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

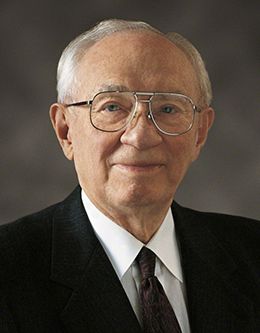

Gordon B. Hinckley was First Counselor in the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 13 October 1992.