I am honored to be with you this morning. It is no small or insignificant or unimportant thing to intrude upon the time and attention of so many thousands of you. Thank you for coming. I pray that I may be directed by the Spirit to say something to you which will be useful in your lives.

Welcome to Students

I am here for two assigned purposes. The first is to welcome you on behalf of the First Presidency of the Church, who stand as the president and vice-presidents of the Board of Trustees, to this new academic year. The second is to dedicate the John Taylor Building on this campus.

As President Holland has explained, it has been customary over a period of many years for the president of the Church to meet with you each fall. I regret that President Kimball has found it necessary to excuse himself this morning. Your disappointment is no greater than is my own. I am pleased to report that he is getting along well. He meets with us almost every morning. He was with us this morning. The last thing I did before leaving to come here was to talk with him. We greatly appreciate that association. He is the Prophet of the Lord in this day. We honor him as such and look to him for guidance. He gives us inspiration, and we are grateful for it. I assure you that no major decision is reached by the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve, and no policy is implemented that impacts upon the membership of the Church without his approval. That should be reassuring to the membership of the Church who sustain him as prophet, seer, and revelator. Such he is, and of this I bear testimony to you.

I bring you his love and blessing. I bring also the love and blessing of his devoted and inspired counselors, President Tanner and President Romney. The Brethren in whose behalf I speak have great love and appreciation for this tremendous institution. They have great expectations concerning you, its student body. They and their associates of the Board of Trustees have allocated from the general funds of the Church, which are sacred trust funds, millions of dollars that have come from the consecrations of the members of the Church across the world, to make it possible for you to be here and drink at the fountains of knowledge, both secular and spiritual.

In so doing they have placed upon you a great and sacred trust. As a few thousand among the millions of Church members, you occupy a unique and enviable position. Yours is the opportunity to attend Brigham Young University, the university of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, here to study under a faculty of men and women of learning and of faith. There are many wonderful colleges and universities on this continent. But BYU is unique. It is the largest private university in America, and that is an indication of the great beneficence of the church which supports it and of the board which has responsibility for its operation. Furthermore, its plant, its programs, and its faculty are unexcelled. Most important, there exists a guiding determination on the part of its board that the Spirit of God shall be constantly invited as an overriding component of the environment in which you live and work while you are here.

BYU ought to be the very best in the entire world. Reflect for a moment upon the motto of this institution—“The glory of God is intelligence.” You who have come here to study are walking the road that leads to immortality, eternal life, and that glory whose very essence is pure and godly and eternal intelligence.

I cannot emphasize too strongly the need on your part to take advantage of the tremendous opportunity that lies ahead of you as you begin this academic year. You must qualify yourselves with skills and with flexibility to meet the challenges of a changing society. I recently read a provocative monograph, dealing with a thesis on “the restructuring of America in the decade ahead.” It emphasized that our society is changing far more rapidly than most of us realize.

This study pointed out that we are moving from an industrial to an information society:

In 1950, 65% of the U.S. work force was engaged in industrial occupations. Since 1950, that 65% has dropped to 27%. . . . In 1950, about 17% of the work force was in information jobs (those involved with creating, processing, and distributing information)—today that figure is up to 60%—and the projection is that 80% of the U.S. work force will be in information jobs by the year 2000. [John Naisbitt, “The Restructuring of America,” Society of Chartered Property and Casualty Underwriters]

This study further points out that we are moving from a centralized to a decentralized society. There is a new federalism spoken of in Washington. The demise of the great, large-circulation magazines such as Life, Look, and Saturday Evening Post is indicative of this decentralization. “There are now more than 4,000 special interest magazines being published in the United States, and no huge circulation, general purpose magazines.”

The study goes on to talk of a shift from a national economy to a global economy. We in the United States have witnessed some of this in the automobile and electronics industries. Once we were the preeminent producers of automobiles. There are now eighty-six countries that have automobile assembly plants.

“We now have two economies in America, one falling and one rising. We have a group of sunset industries and a group of sunrise industries” (Public Affairs Forum C.P.C.U., vol. 3, no. 1).

These shifts, which are going on all about us and which will continue in the years ahead, make education so very necessary—first, to recognize them; and secondly to be prepared to adjust to them. The competitive pressures will be tremendous as the Third World gears for increasing industrial capacity which in the past has been in other hands. I am convinced that the faculty of this university will face greater challenges than they have known in a long while. We must keep abreast of the times—no, we must keep ahead of them. This is one of the great responsibilities of education, to anticipate and to prepare for that which inevitably will come.

There is another evolution or revolution that has been going on. This too has created and will continue to create tremendous challenges, and particularly for the graduates of this institution.

Jim Bishop, prominent columnist, recently wrote as follows: “This is the twentieth year of America’s Rotten Revolution. Two decades ago, this nation began its slide down the drain. It moved faster, more destructively, than the fall of the Roman Empire.” He quoted from a book by Marvin Harris to be published this November by Simon and Schuster under the title Why America Changed. He spoke of the moral decline, the decline of ethics and principle. And then he concluded: “It was, no matter how you gauge it, a Rotten Revolution. America has paid dearly for greed on all levels. We cannot wish our way back to strength. The only way is to restore the morals we had in our innocence.”

I am, by nature, an optimist. But no one, it seems to me, can be blind to the tremendous forces that are slapping our society. I received my baccalaureate degree fifty years ago, in the depression-ridden year of 1932. None of you students here today really has any idea of the economic darkness of those times. To be thrown onto the employment market in those times was like being cast into the sea to swim through heavy waves. Unemployment reached 30 percent. People committed suicide in despair. If a man had a job earning a hundred dollars a month, he was considered fortunate. Men who had been profitably employed found themselves standing in soup lines and living in shantytowns.

But with all of this, it seems to me, as I reflect on those days, there was something of tremendous good in the people. There was a spirit of mutual helpfulness, a spirit of respect one for another and, generally speaking, a high moral tone. Of course there was crime, even gang crime. There were the rumrunners and the moonshiners. There were even those who wished for arrest and conviction so that they could trade the cold of the outside for the warmth of jail. But, at least in the society of which I was a part as a young man, there was a great—and what I regard as wonderful—respect for women. Homosexuality was almost unheard of. The use of hard drugs was practically unknown.

We have traveled far since then, and the results are told in our statistics, of crime, divorce, and a long and sickening train of various immoralities.

And so, my dear young friends, as we welcome you this new academic year, we expect, and we hope you expect, to make the very most of the great and challenging opportunities you have before you—on the one hand, to equip yourselves for the changing and competitive world in which you will earn your livelihood, and, on the other hand, to cultivate a compelling loyalty to the unchanging and ever-constant principles of morality, integrity, and eternal truth which must undergird the character of every good man and woman, and every progressive society.

The John Taylor Building

Now, this brings me to the second reason for my being here, and that is to dedicate the John Taylor Building. I am grateful that we are now naming on this campus a structure for this remarkable man who sometimes is little remembered in this generation. Our studies of him are diminished, in comparison, by our studies of the two great men who preceded him as presidents of the Church, Joseph Smith and Brigham Young.

John Taylor was a remarkable man, whose life and example we ought to study more.

He was a man of principle, integrity, and fidelity. He was born in the lake country of Westmorland, that magnificently beautiful area of England where the deep waters of Windermere, Grasmere, and Morcombe Bay lend a quality to the environment that is exhilerating simply to inhale. I have been there, and I have tasted of that beauty. Here he grew through his childhood and youth and at the age of seventeen became a Methodist lay minister. A few years later he came to the New World and in 1832 settled in Toronto. It was here that his path crossed the path of Parley P. Pratt, who had been sent on a mission to Canada under a prophecy of Heber C. Kimball that there he would find a people ready to receive him, and that out of that service would come a harvest which would lead, among other things, to the spread of the work to the British Isles.

The story of the fulfillment of that remarkable prophecy is too long for this telling. Suffice it to say that John Taylor and his wife were baptized into the Church in 1836 through the labors of Parley Pratt who said, “The people there drank in truth as water, and loved it as they loved life” (PPP, p. 152). Thereafter, until the day of his death, John Taylor, the convert, was an unflinching and powerful exponent of the truths which had come into his life and which had taken possession of all his loyalties. He selected as his motto, “The kingdom of God or nothing.” With that motto as his anchor, his life became the fulfillment of that marvelous promise given by the Lord through revelation when he said: “And if your eye be single to my glory, your whole bodies shall be filled with light, and there shall be no darkness in you” (D&C 88:67). He met Joseph Smith, and there came into his heart a great and powerful conviction that this man was indeed a prophet of God.

John Taylor said on one occasion: “I do not believe in a religion that cannot have all my affections, but in a religion for which I can both live and die. I would rather have God for my friend than all other influences and powers” (G. B. Hinckley, Truth Restored [Salt Lake City: Corporation of the President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1947], p. 140).

He believed this. He lived it. He advocated it by his example. He was a man of absolute fidelity and loyalty to Him whom he accepted as his leader.

He responded to calls twice to go to England, on another occasion to go to France, on another occasion to go to the Eastern States, and on yet another occasion to plead the cause of the Saints in Washington.

In the dark and troubled days of Nauvoo, when a number of those who had been close to the Prophet turned against him, John Taylor was one who remained at his side with absolute loyalty. There were traitors in those days, men who clandestinely connived against the Prophet. There was another group, the members of which professed belief but who spent much time criticizing and finding fault rather than holding the work together and building the kingdom. Selfishness and pride, and a lust for power and attention took possession of them. All this dissention reached its climax on the tragic day of 27 June 1844, when Joseph and Hyrum Smith were killed by the mob in Carthage Jail. There were two good men with them in that jail at that time. One was Willard Richards, who miraculously escaped injury; and the other was John Taylor, who was savagely wounded, four balls having entered his body from the pistols of the mob. The watch which he carried in his pocket stopped the one which likely would have taken his life. He would have given that life. Concerning his coming into the Church he had said:

I expected when I came into this Church, that I should be persecuted and proscribed. I expected that the people would be persecuted. But I believed that God had spoken, that the eternal principles of truth had been revealed, and that God had a work to accomplish which was in opposition to the ideas, views, and notions of men, and I did not know but it would cost me my life before I got through. . . .

Was there anything surprising in all this? No. If they killed Jesus in former times, would not the same feeling and influence bring about the same results in these times? I had counted the cost when I first started out, and stood prepared to meet it. [JD 25:91–92]

It was he who wrote what we now have as section 135 of the Doctrine and Covenants concerning the death of Joseph Smith, saying:

Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer of the Lord, has done more, save Jesus only, for the salvation of men in this world, than any other man that ever lived in it. . . .He lived great, and he died great in the eyes of God and his people; and like most of the Lord’s anointed in ancient times, has sealed his mission and his works with his own blood; and so has his brother Hyrum. [D&C 135:3]

It was that kind of loyalty to his leader, it was that kind of fidelity to the cause to which he had given his life, that sustained that cause and kept it moving forward in the dark and troubled days that lay ahead. John Taylor’s faith in those difficult times was unmistakable. Listen to his words on the position of the Church in that fateful year of 1844:

The idea of the church being disorganized and broken up because of the Prophet and Patriarch being slain, is preposterous. This church has the seeds of immortality in its midst. It is not of man, nor by man—it is the offspring of Deity: it is organized after the pattern of heavenly beings, through the principles of revelation; by the opening of the heavens, by the ministering of angels, and the revelations of Jehovah. It is not affected by the death of one or two, or fifty individuals. . . . Times and seasons may change, revolution may succeed revolution, thrones may be cast down, and empires be dissolved, earthquakes may rend the earth from centre to circumference, the mountains may be hurled out of their places, and the mighty ocean be moved form its bed; but amidst the crash of worlds and the crack of matter, truth, eternal truth must remain unchanged, and those principles which God has revealed to his Saints be unscathed amidst the warring elements, and remain as firm as the throne of Jehovah. [Times and Seasons 5:744, December 15, 1844]

Such is the nature of the man we honor today. How appropriate that a building on this great campus be named to his memory. How marvelous his example to all of us who will accept it and live by it. We have those in the Church these days, as there were in Nauvoo, who profess membership but spend much of their time in criticizing, in finding fault, and in looking for defects in the Church, in its leaders, in its programs. They contribute nothing to the building of the kingdom. They rationalize their efforts, trying to justify with pretenses of doing good for the cause, but the result of those efforts is largely only a fragmentation of faith, their own and that of others. How different the motto and the life of the man we remember today: “The kingdom of God or nothing.” I commend it to each of you as a standard for your own lives.

God bless his memory to our good and his life as our example, I pray in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

Now, if you will bow your heads and close your eyes, we shall join in a prayer of dedication.

Dedicatory Prayer

Our beloved Father in Heaven, thou who art our Father and our God, we bow before thee this day in solemn prayer with grateful hearts. We are met on the campus of this great institution which is operated in thy name and in the name of thy beloved Son, the Lord Jesus Christ. We are thankful for this university with its faculty and all of it facilities, and for the great student body who have come here to learn with hope and desire, and with faith and prayer.

We reflect today upon those who have gone before us who laid the foundations of the great work of which we are a part—thine anointed servant, the Prophet Joseph Smith, and those who have succeeded him in that high and sacred office down to him who stands in that office today, even President Spencer W. Kimball, for whom we pray.

On this occasion we particularly remember with appreciation the third President of the Church, President John Taylor, whom thou didst bless and whose mind thou didst touch so that he received the teachings of everlasting truth and who thereafter with great courage, and with faith and fidelity loyally walked as one who was a convert in very deed and who became a great and powerful exponent, even that he came to be known as “the Champion of Liberty.” We thank thee for the life of President John Taylor. We thank thee for his leadership. We thank thee for his great example. We thank thee for those of his descendents who are with us this day and ask thy special blessings upon them that they may always remember him who was their forebear, who walked in faith and with courage and great capacity as an exponent of thy word.

Now, Father, we are here to dedicate a structure named in his memory, even the John Taylor Building. In the authority of the holy priesthood which we hold, and in behalf of all who are present, we dedicate the John Taylor Building on the campus of the Brigham Young University for the great purposes for which it has been constructed, that it may stand on this campus as a place of beauty, yes, but, more importantly, as a place of learning as well as of teaching, as a place of service, as a place of helpfulness, and that all who are housed here may have in their hearts a great sense of service to those who come seeking assistance. We pray that thou wilt bless them with a love for humanity, for this building is presently used to house those departments of the university and of the Church which are designed to look after the needs of those who need help of many kinds. Dear Father, bless those who are there to serve that they may do so with kindness and with love and in the Spirit of thy Son whose life was the very essence of love and service to others.

We pray that thy watchcare may be over this building that it may stand on this campus with its associate buildings as a great tribute to the beneficence of the Church which operates this university. May the name of John Taylor receive a new emphasis and a new attention as a result of the presence of this building on this campus, and may all who enter its portals be constrained to reflect in their minds upon the life, the strength, the faith, and the example of him whose name it carries. To this end we seek thy blessing on this day of dedication, and, in so doing, we dedicate ourselves anew to thy service in the name of thy beloved Son, even the Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

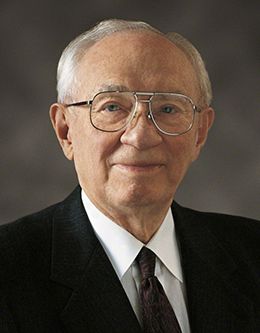

Gordon B. Hinckley was a member of the First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at Brigham Young University on 14 September 1982.