“The weightier matters that move us toward our goals of eternal life are love of God, obedience to his commandments, and unity in accomplishing the work of his Church.”

My title and subject today is taken from the Savior’s denunciation of the scribes and Pharisees: “Ye pay tithe of mint and anise and cummin, and have omitted the weightier matters of the law, judgment, mercy, and faith: these ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone” (Matthew 23:23; emphasis added).

I wish to speak about some “weightier matters” we might overlook if we allow ourselves to focus exclusively on lesser matters. The weightier matters to which I refer are the qualities like faith and the love of God and his work that will move us strongly toward our eternal goals.

In speaking of weightier matters, I seek to contrast our ultimate goals in eternity with the mortal methods or short-term objectives we use to pursue them. I read in the Universe about Professor Sara Lee Gibb’s message from this pulpit last week. She discussed the difference between earthly perspectives and eternal ones. Then, on Sunday, President Thomas S. Monson reminded you that eternal life is our goal. My message concerns that same contrast, which the Apostle Paul described in these words: “We look not at the things which are seen, but at the things which are not seen: for the things which are seen are temporal; but the things which are not seen are eternal” (2 Corinthians 4:18).

If we concentrate too intently on our obvious earthly methods or objectives, we can lose sight of our eternal goals, which the apostle called “things . . . not seen.” If we do this, we can forget where we should be headed and in eternal terms go nowhere. We do not improve our position in eternity just by flying farther and faster in mortality, but only by moving knowledgeably in the right direction. As the Lord told us in modern revelation, “That which the Spirit testifies unto you . . . ye should do in all holiness of heart, walking uprightly before me, considering the end of your salvation” (D&C 46:7; emphasis added).

We must not confuse means and ends. The vehicle is not the destination. If we lose sight of our eternal goals, we might think the most important thing is how fast we are moving and that any road will get us to our destination. The Apostle Paul described this attitude as “hav[ing] a zeal of God, but not according to knowledge” (Romans 10:2). Zeal is a method, not a goal. Zeal—even a zeal toward God—needs to be “according to knowledge” of God’s commandments and his plan for his children. In other words, the weightier matter of the eternal goal must not be displaced by the mortal method, however excellent in itself.

Thus far I have spoken in generalities. Now I will give three examples.

Family

All Latter-day Saints understand that having an eternal family is an eternal goal. Exaltation is a family matter, not possible outside the everlasting covenant of marriage, which makes possible the perpetuation of glorious family relationships. But this does not mean that everything related to mortal families is an eternal goal. There are many short-term objectives associated with families—such as family togetherness or family solidarity or love—that are methods, not the eternal goals we pursue in priority above all others. For example, family solidarity to conduct an evil enterprise is obviously no virtue. Neither is family solidarity to conceal and perpetuate some evil practice like abuse.

The purpose of mortal families is to bring children into the world, to teach them what is right, and to prepare all family members for exaltation in eternal family relationships. The gospel plan contemplates the kind of family government, discipline, solidarity, and love that serve those ultimate goals. But even the love of family members is subject to the overriding first commandment, which is love of God (see Matthew 22:37–38) and “if ye love me, keep my commandments” (John 14:15). As Jesus taught, “He that loveth father or mother more than me is not worthy of me: and he that loveth son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me” (Matthew 10:37).

Choice or Agency

My next example in this message on weightier matters is the role of choice or agency.

Few concepts have more potential to mislead us than the idea that choice or agency is an ultimate goal. For Latter-day Saints, this potential confusion is partly a product of the fact that moral agency—the right to choose—is a fundamental condition of mortal life. Without this precious gift of God, the purpose of mortal life could not be realized. To secure our agency in mortality we fought a mighty contest the book of Revelation calls a “war in heaven.” This premortal contest ended with the devil and his angels being cast out of heaven and being denied the opportunity of having a body in mortal life (see Revelation 12:7–9).

But our war to secure agency was won. The test in this postwar mortal estate is not to secure choice but to use it—to choose good instead of evil so that we can achieve our eternal goals. In mortality, choice is a method, not a goal.

Of course, mortals must still resolve many questions concerning what restrictions or consequences should be placed upon choices. But those questions come under the heading of freedom, not agency. Many do not understand that important fact. For example, when I was serving here at BYU, I heard many arguments on BYU’s Honor Code or dress and grooming standards that went like this: “It is wrong for BYU to take away my free agency by forcing me to keep certain rules in order to be admitted or permitted to continue as a student.” If that silly reasoning were valid, then the Lord, who gave us our agency, took it away when he gave the Ten Commandments. We are responsible to use our agency in a world of choices. It will not do to pretend that our agency has been taken away when we are not free to exercise it without unwelcome consequences.

Because choice is a method, choices can be exercised either way on any matter, and our choices can serve any goal. Therefore, those who consider freedom of choice as a goal can easily slip into the position of trying to justify any choice that is made. “Choice” can even become a slogan to justify one particular choice. For example, in the 1990s, one who says “I am pro-choice” is clearly understood as opposing any legal restrictions upon a woman’s choice to abort a fetus at any point in her pregnancy.

More than 30 years ago, as a young law professor, I published one of the earliest articles on the legal consequences of abortion. Since that time I have been a knowledgeable observer of the national debate and the unfortunate Supreme Court decisions on the so-called “right to abortion.” I have been fascinated with how cleverly those who sought and now defend legalized abortion on demand have moved the issue away from a debate on the moral, ethical, and medical pros and cons of legal restrictions on abortion and focused the debate on the slogan or issue of choice. The slogan or sound bite “pro-choice” has had an almost magical effect in justifying abortion and in neutralizing opposition to it.

Pro-choice slogans have been particularly seductive to Latter-day Saints because we know that moral agency, which can be described as the power of choice, is a fundamental necessity in the gospel plan. All Latter-day Saints are pro-choice according to that theological definition. But being pro-choice on the need for moral agency does not end the matter for us. Choice is a method, not the ultimate goal. We are accountable for our choices, and only righteous choices will move us toward our eternal goals.

In this effort, Latter-day Saints follow the teachings of the prophets. On this subject our prophetic guidance is clear. The Lord commanded, “Thou shalt not . . . kill, nor do anything like unto it” (D&C 59:6). The Church opposes elective abortion for personal or social convenience. Our members are taught that, subject only to some very rare exceptions, they must not submit to, perform, encourage, pay for, or arrange for an abortion. That direction tells us what we need to do on the weightier matters of the law, the choices that will move us toward eternal life.

My young brothers and sisters, in today’s world we are not true to our teachings if we are merely pro-choice. We must stand up for the right choice. Those who persist in refusing to think beyond slogans and sound bites like pro-choice wander from the goals they pretend to espouse and wind up giving their support to results they might not support if those results were presented without disguise.

For example, consider the uses some have made of the possible exceptions to our firm teachings against abortion. Our leaders have taught that the only possible exceptions are when the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest, or a competent physician has determined that the life or health of the mother is in serious jeopardy, or the fetus has severe defects that will not allow the baby to survive beyond birth. But even these exceptions do not justify abortion automatically. Because abortion is a most serious matter, we are counseled that it should be considered only after the persons responsible have consulted with their bishops and received divine confirmation through prayer.

Some Latter-day Saints say they deplore abortion, but they give these exceptional circumstances as a basis for their pro-choice position that the law should allow abortion on demand in all circumstances. Such persons should face the reality that the circumstances described in these three exceptions are extremely rare. For example, conception by incest or rape—the circumstance most commonly cited by those who use exceptions to argue for abortion on demand—are involved in only a tiny minority of abortions. More than 95 percent of the millions of abortions performed each year extinguish the life of a fetus conceived by consensual relations. Thus the effect in over 95 percent of abortions is not to vindicate choice but to avoid its consequences (see Russell M. Nelson, “Reverence for Life,”Ensign, May 1985, pp. 11–14). Using arguments of “choice” to try to justify altering the consequences of choice is a classic case of omitting what the Savior called “the weightier matters of the law.”

A prominent basis for the secular or philosophical arguments for abortion on demand is the argument that a woman should have control over her own body. Just last week I received a letter from a thoughtful Latter-day Saint outside the United States who analyzed that argument in secular terms. Since his analysis reaches the same conclusion I have urged on religious grounds, I quote it here for the benefit of those most subject to persuasion on this basis:

Every woman has, within the limits of nature, the right to choose what will or will not happen to her body. Every woman has, at the same time, the responsibility for the way she uses her body. If by her choice she behaves in such a way that a human fetus is conceived, she has not only the right to, but also the responsibility for that fetus. If it is an unwanted pregnancy, she is not justified in ending it with the claim that it interferes with her right to choose. She herself chose what would happen to her body by risking pregnancy. She had her choice. If she has no better reason, her conscience should tell her that abortion would be a highly irresponsible choice.

What constitutes a good reason? Since a human fetus has intrinsic and infinite human value, the only good reason for an abortion would be the violation or deprivation of, or the threat to the woman’s right to choose what will or will not happen to her body. Social, educational, financial, and personal considerations alone do not outweigh the value of the life that is in the fetus. These considerations by themselves may properly lead to the decision to place the baby for adoption after its birth, but not to end its existence in utero.

The woman’s right to choose what will or will not happen to her body is obviously violated by rape or incest. When conception results in such a case, the woman has the moral as well as the legal right to an abortion because the condition of pregnancy is the result of someone else’s irresponsibility, not hers. She does not have to take responsibility for it. To force her by law to carry the fetus to term would be a further violation of her right. She also has the right to refuse an abortion. This would give her the right to the fetus and also the responsibility for it. She could later relinquish this right and this responsibility through the process of placing the baby for adoption after it is born. Whichever way is a responsible choice.

The man who wrote those words also applied the same reasoning to the other exceptions allowed by our doctrine—life of the mother and a baby that will not survive birth.

I conclude this discussion of choice with two more short points.

If we say we are anti-abortion in our personal life but pro-choice in public policy, we are saying that we will not use our influence to establish public policies that encourage righteous choices on matters God’s servants have defined as serious sins. I urge Latter-day Saints who have taken that position to ask themselves which other grievous sins should be decriminalized or smiled on by the law on this theory that persons should not be hampered in their choices. Should we decriminalize or lighten the legal consequences of child abuse? of cruelty to animals? of pollution? of fraud? of fathers who choose to abandon their families for greater freedom or convenience?

Similarly, some reach the pro-choice position by saying we should not legislate morality. Those who take this position should realize that the law of crimes legislates nothing but morality. Should we repeal all laws with a moral basis so our government will not punish any choices some persons consider immoral? Such an action would wipe out virtually all of the laws against crimes.

Diversity

My last illustration of the bad effects of confusing means and ends, methods and goals, concerns the word diversity. Not many labels have been productive of more confused thinking in our time than this one. A respected federal judge recently commented on current changes in culture and values by observing that “a new credo in celebration of diversity seems to be emerging which proclaims, ‘Divided We Stand!’” (J. Thomas Greene, “Activist Judicial Philosophies on Trial,” Federal Rules Decisions 178 [1997]: 200). Even in religious terms, we sometimes hear “celebrations of diversity,” as if diversity were an ultimate goal.

The word diversity has legitimate uses to describe a condition, such as when President Bateman referred in last summer’s Annual University Conference to the “racial and cultural diversity” of BYU (Merrill J. Bateman, “Brigham Young University in the New Millennium,” BYU 1997–98 Speeches [Provo: BYU, 1998], p. 366). Similarly, what we now call “diversity” appears in the scriptures as a condition. This is evident wherever differences among the children of God are described, such as in the numerous scriptural references to nations, kindreds, tongues, and peoples.

In the scriptures, the objectives we are taught to pursue on the way to our eternal goals are ideals like love and obedience. These ideals do not accept us as we are but require each of us to make changes. Jesus did not pray that his followers would be “diverse.” He prayed that they would be “one” (John 17:21–22). Modern revelation does not say, “Be diverse; and if ye are not diverse, ye are not mine.” It says, “Be one; and if ye are not one ye are not mine” (D&C 38:27).

Since diversity is a condition, a method, or a short-term objective—not an ultimate goal—whenever diversity is urged it is appropriate to ask, “What kind of diversity?” or “Diversity in what circumstance or condition?” or “Diversity in furtherance of what goal?” This is especially important in our policy debates, which should be conducted not in terms of slogans but in terms of the goals we seek and the methods or shorter-term objectives that will achieve them. Diversity for its own sake is meaningless and can clearly be shown to lead to unacceptable results. For example, if diversity is the underlying goal for a neighborhood, does this mean we should take affirmative action to assure that the neighborhood includes thieves and pedophiles, slaughterhouses and water hazards? Diversity can be a good method to achieve some long-term goal, but public policy discussions need to get beyond the slogan to identify the goal, to specify the proposed diversity, and to explain how this kind of diversity will help to achieve the agreed goal.

Our Church has an approach to the obvious cultural and ethnic diversities among our members. We teach that what unites us is far more important than what differentiates us. Consequently, our members are asked to concentrate their efforts to strengthen our unity—not to glorify our diversity. For example, our objective is not to organize local wards and branches according to differences in culture or in ethnic or national origins, although that effect is sometimes produced on a temporary basis when required because of language barriers. Instead, we teach that members of majority groupings (whatever their nature) are responsible to accept Church members of other groupings, providing full fellowship and full opportunities in Church participation. We seek to establish a community of Saints—“one body” the Apostle Paul called it (1 Corinthians 12:13)—where everyone feels needed and wanted and where all can pursue the eternal goals we share.

Consistent with the Savior’s command to “be one,” we seek unity. On this subject President Gordon B. Hinckley has taught:

I remember when President J. Reuben Clark, Jr., as a counselor in the First Presidency, would stand at this pulpit and plead for unity among the priesthood. I think he was not asking that we give up our individual personalities and become as robots cast from a single mold. I am confident he was not asking that we cease to think, to meditate, to ponder as individuals. I think he was telling us that if we are to assist in moving forward the work of God, we must carry in our hearts a united conviction concerning the great basic foundation stones of our faith. . . . If we are to assist in moving forward the work of God, we must carry in our hearts a united conviction that the ordinances and covenants of this work are eternal and everlasting in their consequences. [TGBH, p. 672]

Anyone who preaches unity risks misunderstanding. The same is true of anyone who questions the goal of diversity. Such a one risks being thought intolerant. But tolerance is not jeopardized by promoting unity or by challenging diversity. Again, I quote President Hinckley:

Each of us is an individual. Each of us is different. There must be respect for those differences. . . .

. . . We must work harder to build mutual respect, an attitude of forbearance, with tolerance one for another regardless of the doctrines and philosophies which we may espouse. Concerning these you and I may disagree. But we can do so with respect and civility. [TGBH, pp. 661, 665]

President Hinckley continues:

An article of the faith to which I subscribe states: “We claim the privilege of worshipping Almighty God according to the dictates of our own conscience, and allow all men the same privilege, let them worship how, where, or what they may” (Article of Faith 11). I hope to find myself always on the side of those defending this position. Our strength lies in our freedom to choose. There is strength even in our very diversity. But there is greater strength in the God-given mandate to each of us to work for the uplift and blessing of all His sons and daughters, regardless of their ethnic or national origin or other differences.[TGBH, p. 664]

In short, we preach unity among the community of Saints and tolerance toward the personal differences that are inevitable in the beliefs and conduct of a diverse population. Tolerance obviously requires a non-contentious manner of relating toward one another’s differences. But tolerance does not require abandoning one’s standards or one’s opinions on political or public policy choices. Tolerance is a way of reacting to diversity, not a command to insulate it from examination.

Strong calls for diversity in the public sector sometimes have the effect of pressuring those holding majority opinions to abandon fundamental values to accommodate the diverse positions of those in the minority. Usually this does not substitute a minority value for a majority one. Rather, it seeks to achieve “diversity” by abandoning the official value position altogether, so that no one’s value will be contradicted by an official or semiofficial position. The result of this abandonment is not a diversity of values but an official anarchy of values. I believe this is an example of BYU visiting professor Louis Pojman’s observation in a recent Universe Viewpoint (October 13, 1998, p. 4) that diversity can be used “as a euphemism for moral relativism.”

There are hundreds of examples of this, where achieving the goal of diversity results in the anarchy of values we call moral relativism. These examples include such varied proposals as forbidding the public schools to teach the wrongfulness of certain behavior or the rightfulness of patriotism and includes attempting to banish a representation of the Ten Commandments from any public buildings.

In a day when prominent thinkers like James Billington and Allan Bloom have decried the fact that our universities have stopped teaching right and wrong, we are grateful for the countercultural position we enjoy at BYU. Moral relativism, which is said to be the dominant force in American universities, has no legitimate place at Brigham Young University. Our faculty teach values—the right and wrong taught in the gospel of Jesus Christ—and students come to BYU for that teaching.

In conclusion, diversity and choice are not the weightier matters of the law. The weightier matters that move us toward our goals of eternal life are love of God, obedience to his commandments, and unity in accomplishing the work of his Church. In this belief and practice we move against the powerful modern tides running toward individualism and tolerance rather than toward obedience and cooperative action. Though our belief and practice is unpopular, it is right, and it does not require the blind obedience or the stifling uniformity its critics charge. If we are united on our eternal goal and united on the inspired principles that will get us there, we can be diverse on individual efforts in support of our goals and consistent with those principles.

We know that the work of God cannot be done without unity and cooperative action. We also know that the children of God cannot be exalted as single individuals. Neither a man nor a woman can be exalted in the celestial kingdom unless both unite in the unselfishness of the everlasting covenant of marriage and unless both choose to keep the commandments and honor the covenants of that united state.

I testify of Jesus Christ, our Savior. As the One whose atonement paid the incomprehensible price for our sins, he is the One who can prescribe the conditions for our salvation. He has commanded us to keep his commandments (see John 14:15) and to “be one” (D&C 38:27). I pray that we will make the wise choices to keep the commandments and to seek the unity that will move us toward our ultimate goal, “eternal life, which gift is the greatest of all the gifts of God” (D&C 14:7). I say this in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

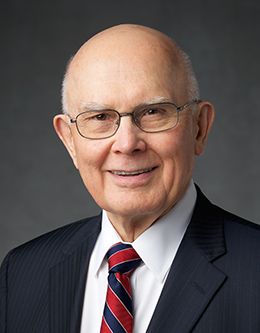

Dallin H. Oaks was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this devotional address was given at BYU on 9 February 1999 .