Meeting the Challenges of the Nineties

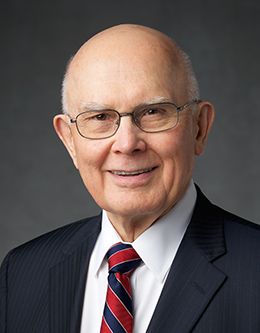

Of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

August 28, 1990

Of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles

August 28, 1990

The Church has positioned BYU to have an enormous impact on the youth of the Church, its future leaders.

June and I are glad to be with you this evening. During our nine years at BYU, we always looked on these preschool dinners as a special treat, and we still have that feeling ten years after our departure.

A lot can happen in a decade. A lot has happened in the ten years since we left BYU.

In 1980 only a million Americans were using computers. Today it is over 50 million.

Ten years ago hardly any if us had heard of a compact disc, a fax machine, or a VCR. Today their presence and influence are pervasive.

In 1980 the savings and loan industry was thriving and there was talk about deregulation. Today that industry is in a shambles, and government officials are arguing about whether the cure will cost the government $100 billion or $200 billion.

In 1980 there were just over 4 1/2 million members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Ten years later, we have grown by 57 percent to 7 1/3 million members in over 11,000 wards and more thousands of branches throughout the world.

Just ten years ago this month, I was the BYU commencement speaker. Having just concluded my nine years as president of BYU, I used that occasion to look ahead to the next decade. I titled my talk “Challenges to BYU in the Eighties” (15 August 1980).

By coincidence, I have this pulpit again, just ten years later. The temptation to quote some of my predictions and compare them with the actual experience of the eighties is irresistible.

I began my 1980 remarks with this status report, which we can now compare with BYU’s current standing:

After emerging from its educational adolescence, BYU has now achieved the status of a young adult in the world society of universities. We are mature in the range of our activities, but not yet fully mature in the quality of most of our programs or in the scholarly standing of a majority of our faculty. . . .

It will take an accumulation of accomplishments before we have attained the standing prophesied by the First Presidency nine years ago: “Because of its unique combination of revealed and secular learning, Brigham Young University is destined to become a leader among the great universities of the world.”

I continued with this challenge. You can judge whether it still applies ten years later:

One of the greatest obstacles on the way to our destiny is complacency, the thought that we have already arrived or that accomplishment or standing will come as an effortless handout to a worthy few who take no thought except to rely on Divine intervention.

The greater part of that 1980 commencement address reviewed what I then called “Problems in the Eighties.” I predicted that the principal problems for higher education in the decade of the eighties would be enrollment and money.

For the past several years BYU’s income has not kept pace with inflation. Although both its tuition revenues and its Church appropriations have been increased from 8 to 10 percent annually, the University’s costs have increased at an even higher rate. . . .

The cumulative effect of this cost-price squeeze over the past several years and into the foreseeable future is to reduce the standard of living of the University and its personnel. In fact, that is the outlook for the next decade for most Americans. We will have to accept a reduced standard of living as a consequence of increased international prices for energy, our unfavorable balance of payments, and the diminished rate of increase in our nation’s total productivity.

In this financial climate, Brigham Young University must get along on less, and so must the persons it employs. If we are to have sufficient funds for what is essential, we must forego some things that are not.

Departing from that text for a moment, I will observe that many residents of Utah—presumably including some members of the BYU community—have not accepted and acted upon the need for a reduced standard of living. The relatively poor national ranking of Utah on bankruptcy filings, payment of telephone bills, and delinquency rates in bank, credit union, and consumer loans all suggest that the predominantly Latter-day Saint people of this state are borrowing and living beyond their means. I might add that our national government’s huge and persistent annual deficits show that this is a national rather than a local affliction.

In terms of living within a diminished income, local Church leaders who have had to fit their programs within the stringent limits of the Church’s new local unit budget program are providing a worthy example for all of us.

I continue to quote from the 1980 commencement address:

Fortunately, . . . BYU is approaching the time when the numbers and financial position of its alumni can provide very significant revenues from annual giving. . . . Increased private support is vital if the University is to preserve its commitment to excellence in a decade of unusual fiscal challenge.

The most difficult financial problem of the eighties could be faculty compensation. BYU cannot reach its destiny without a faculty whose credentials and accomplishments are world-class.

Here I talked about the need to be competitive versus the importance of retaining the spirit of sacrifice. I concluded that subject as follows:

I wish I had a formula for balancing the countervailing pressures of market and sacrifice. We must not lose the spirit of sacrifice in employment at Brigham Young University, but neither must that sacrifice be exploited or become an excuse for unrealistic compensation policies in the University. After nine years of worrying over this problem, I have now left it behind for President Holland as one of the problems I have been unable to solve or ameliorate. I suspect that the only feasible solution is to be explicit about the issue, but to leave it to be balanced and resolved in the hearts and minds of individual faculty members and administrators.

I suppose President Holland grappled with that problem and then left it to President Lee, who will do the same. Those of us who are impatient with the time it takes to solve really difficult problems confirm the observation that “Nothing is impossible for the man who doesn’t have to do it himself” (Arthur Block, Murphy’s Law, p. 80).

My suggestion that the other major problem in the eighties would be enrollment was both obvious and accurate. In a few minutes I will comment further on that perennial.

Here is what I said on another subject:

I have not listed government regulation as a major challenge of the eighties because I do not expect the regulatory growth rate of the seventies to continue in the next decade. There may be a few new initiatives, but the decade of the 1980s is likely to be a decade of refinement, consolidation, and perhaps some temporary rollbacks in the regulatory tide. Extensive new thrusts in government regulation are likely to be aimed at churches during this period, but probably not at higher education.

Some things don’t change. Last week President Rex E. Lee let me read a copy of the talk he had prepared for the first day of this conference. All of what he said sounded right to me.

It also sounded familiar. I am well acquainted with BYU presidents’ preschool talks for two decades, and their prominent themes have been pretty much the same for that entire period. President Lee’s included:

1. The mission of BYU.

2. BYU’s relationship to its board of trustees, to the Church, and to the mission of the Church.

3. BYU’s stewardship over huge resources provided by the Church—both capital assets and annual support.

4. The relationship between undergraduate and graduate programs at BYU.

5. The preeminence of teaching at BYU.

6. The essential but supportive role of research and scholarly work at BYU.

7. The vital and highly valued work of the BYU staff.

8. The need for each constituent unit of the university and for each member of the faculty, staff, and administration to subordinate personal interests to the overall missions of the university and the Church.

In developing these major themes, President Lee made the following statements, which seem so right to me that in my view the opposite or even a significant qualification is unthinkable:

[Brigham Young University is] an integral part of an inseparable whole, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the restored gospel whose message the Church proclaims. [p. 11]

Each constituent unit of this university should see itself principally as part of the larger university-wide effort. . . . The natural tendency [however] is in the other direction . . . [in which each individual unit comes to be] more concerned with building up [its] own domain. [p. 12]

[Brigham Young University’s] Mount Everest is to be found in undergraduate teaching [p. 13] . . . [because] it is at the undergraduate level that we can do the most of what we want to do at the least cost. [p. 14]

In explaining BYU’s position as a predominantly undergraduate liberal arts institution with selected graduate and professional programs, President Lee said that BYU does not aspire to climb the rungs of the educational ladder to attain the Carnegie Foundation’s higher classifications of Doctorate-Granting or Research University (pp. 11–13). Although he did not mention this, President Lee would also have been correct in saying that there is absolutely no sentiment or support in the board of trustees to move BYU out of its current and unique position as a large predominantly undergraduate university. Consequently, at BYU, research and scholarly work are essential, supportive, and subordinate to the teaching mission of the university.

The fact that BYU is an integral part of the church and the proclaiming of the restored gospel explains the anomalous fact that BYU is the largest single center of church expenditure in the entire world. So far as I am aware, no other church gives a comparable proportion of its financial resources or the trustee time of its top leaders to support and make policy for the postsecondary education.

But financial and leadership support are not the only visible evidence of BYU’s importance to the Church. The Church has positioned BYU to have an enormous impact on the youth of the Church, its future leaders.

In view of BYU’s great importance, the leaders of this Church have a vital, continuing concern with its direction, its accomplishments, and its faculty, staff, and students. These leaders simply will not appropriate the kind of Church resources that are spent here or allow the kind of Church influence that is wielded through the Brigham Young University name and prestige unless those resources and that influence are exerted in support of the mission of the Church. To assure that result, the board of trustees of BYU consists of the First Presidency and other leaders of the Church. And the board of trustees appoints and releases the president, the deans, and other officers of the university and makes the policies they are responsible to execute, including fundamental strategic decisions about emphasis and directions.

President J. Reuben Clark outlined a fundamental principle of Church-sponsored higher education over fifty years ago. Speaking for the First Presidency, he reminded an audience of Church Educational System teachers that the restored gospel of Jesus Christ is not a system of ethics to be rationalized according to secular truth, but a system of eternal truths revealed by our Creator and transcending human reason. He affirmed

that the things of the natural world will not explain the things of the spiritual world; that the things of the spiritual world cannot be understood or comprehended by the things of the natural world; that you cannot rationalize the things of the spirit. [“The Charted Course of the Church in Education,” J. Reuben Clark Selected Papers, p. 248, D. Yarn, ed., 1984]

In this teaching President Clark echoed the Apostle Paul, who said: “But the natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God: for they are foolishness unto him: neither can he know them, because they are spiritually discerned” (1 Corinthians 2:14).

President Clark pleaded for teachers in all the Church’s schools to use the power of testimony to help their students, who seek strengthened faith as well as increased knowledge.

These students hunger and thirst . . . for a testimony of the things of the spirit and of the hereafter, and knowing that you cannot rationalize eternity, they seek faith, and the knowledge which follows faith. They sense by the spirit they have, that . . . one living, burning, honest testimony of a righteous God-fearing man that Jesus is the Christ and that Joseph was God’s prophet, is worth a thousand books and lectures aimed at debasing the Gospel to a system of ethics or seeking to rationalize infinity. [Ibid.]

That kind of testimonied teaching has always taken place at BYU, but it does not happen effortlessly. The teacher who testifies must move against the natural academic tide that runs in universities. I mention this as a challenge for each of us to strengthen our collective resolve to move against that tide.

The pervasive method of teaching gospel principles and values—by example as well as by precept—requires constant and conscious effort. The visible example of faculty leaders is essential and appreciated. I was pleased to witness two conspicuous examples during the remarks at the graduation exercises earlier this month.

In his commencement address this year, Dean Martin B. Hickman expressed appreciation for the collegiality at BYU, observing that collegiality “is most rewarding when it embraces a fellowship of faith as well as a fellowship of mind.” Affirming this duality to the graduates, he expressed the hope that they had experienced what he called “both aspects of BYU, so that, when BYU is only a memory, spiritual experiences as well as learning moments will be reflected in the mosaic of your recollections.” In his closing remarks, he reminded the graduates, newly certified and anxious to begin their working lives or further studies, that “in the end, if you have not cultivated family, faith, and friends, nothing else will matter.”

To cite another example, in his talk at the graduation banquet, Associate Academic Vice President Dennis L. Thompson reminded the graduates of BYU’s unique perspective: “We teach here that value should be the test of desire rather than desire being the test of value; and that spirit adds a dimension to life which makes the difference.”

In order to accomplish its unique mission and further its unique perspective, BYU must be wisely selective in which university practices it accepts and implements and which it does not. For example, since BYU is not a Doctoral-Granting or a Research University according to Carnegie Foundation criteria (though it does important research and grants significant numbers of doctoral degrees), BYU should take care that its criteria for faculty scholarship are not dictated by classifications that are inapplicable to its unique category. BYU should be particularly receptive to the proposals in a 1990 Carnegie Foundation report recently shared with our board of trustees. Universities were urged to broaden their definition of acceptable faculty scholarship beyond the traditional standard of “advancing knowledge” to include “integrating knowledge,” “applying knowledge,” and “supporting teaching.”

BYU’s unique mission also requires that it’s policies and personnel dignify and promote the religious teaching that is vital to that mission. The board of trustees has given particular emphasis to the formal teaching of religion and to the weekend work of the campus stakes and wards. I have no doubt that each member of the university community will pursue his or her conventional university tasks, but experience teaches that from time to time each of us is prone to forget that at BYU it is not enough to be just another university, even the best university according to conventional criteria. BYU has its own mission and standards, and all of us must make extraordinary efforts to promote them.

In my commencement address ten years ago, I described BYU’s unique admissions challenge:

If missionary baptisms continue at their current rate . . . the cumulative effect of current populations and conversions will increase BYU’s total applications by about 40–50 percent by the early 1990s. . . .

Many who are desirous of attending BYU in the 1990s will be turned away. The designation of those who will not be admitted will be extremely painful since most of these young men and women, like those who are admitted, will also be worthy and qualified for college study.

As we enter the decade of the nineties, BYU’s admissions policies are, in fact, among the most difficult problems facing the university. During the past year President Lee and his colleagues have had long discussions with the board of trustees on those policies. Those discussions have not yet concluded, and when they do, any new policy directions will be made known under the direction of the board, and all of us will be bound by them.

In the meantime, I believe I can venture to add something to the public discussion of this subject by stating my own views, which will, of course, be superseded by whatever the board decides on this matter. These are the views of one who has had a unique opportunity to view BYU admissions policies from the standpoint of an educator and parent who has worked and lived in both Utah and in the Midwest, a university president who has had experience administering these admissions policies, and a BYU trustee and Church official who has heard the pleas of parents and students in many parts of the world.

I begin by sharing one of many letters received at Church headquarters in support of the idea that BYU should admit as many young Latter-day Saints as possible. This letter came from a teacher at a university outside the Intermountain West. He was not writing a brief to advocate the admission of his own son or daughter—he was arguing for the young people in his stake.

He described a boy who was skeptical about a mission but decide to serve during a freshman year at BYU. Thousands of freshmen have had that experience at BYU. He reminded “that many young people may be deprived of the possibility of such experiences, simply because they are not students at a Church-related college.” He quoted his stake president’s statement that “the experience of Church schools has a profound impact on the lives of our young people,” and the president’s further observation that “those who have spent most of their lives in the intermountain west or who have raised their children in the security of high-density Mormondom do not fully appreciate the magnitude of this issue.”

President Lee’s own experience, related to you yesterday, is an important second witness. Drawing on his personal experience, he said:

I am convinced that especially during the undergraduate years, [the opportunity to study in the kind of environment where students learn values by precept as well as by example] makes a difference in student attitudes and emerging values and the individual student’s potential for success and happiness. Over the long run, it also has an effect on the development of leadership within the Church.

That reality is important to parents and tithe payers, and it is important to our Church leaders as well.

That reality leads me to believe that the unique faculty and facilities and surroundings of BYU should be made available to serve the maximum number of Latter-day Saint youth who are qualified for rigorous academic work. For example, I believe that two years of BYU experience for 40,000 LDS students is better than four years of BYU experience for 20,000.

Being of that view, I obviously advocate admissions policies that will accommodate large numbers of transfer students. I was glad to notice in the recent graduation exercise that 60 percent of the graduates who received degrees had attended other institutions of higher learning.

I also advocate policies that will encourage all students, four-year and transfer, to accelerate their graduation and departure in order to make spaces for others to enjoy the experiences of BYU. The average age of the bachelor’s degree recipients in the recent graduation was 25 1/2 years of age. If that figure results from a significant number of older students in the student body, I welcome it. If it is a signal that our curriculum policies, graduation requirements, counseling, and the like are acquiescing to students taking 4 1/2 to 5 1/2 years to get a bachelor’s degree, then we have a situation which, in my judgment, cries for correction at a time when we are turning away too many qualified applicants because we have no space for them. If the average graduation time is prolonged by students who take light loads because they have to work extra hours to support themselves and their young families, then we need to take a hard look at our student assistance policies.

My reference to students qualified for rigorous academic work does not imply a belief that we should simply choose that segment of the applicants who have the highest grades and test scores. Because that kind of admissions criteria produces an elitist atmosphere that would not serve the interests of the Church or the student body, we are already giving weight to the quality of the applicant’s preparation, measured by the type of courses taken. We must continue to develop ways to measure and give weight to some other qualities like faith, heart, wisdom, and motivation, which, in combination with more numerical criteria, qualify young men and women for the leadership and accomplishments we seek to serve in this university.

Perhaps a personal experience will help explain why I believe it is so important not to rely solely on grades and test scores. Many in this audience will be familiar with the Law School Admissions Test. It is supposed to measure aptitude for law study. Most law schools attach heavy weight to the LSAT score in their admissions decisions. I was privileged to go to a good law school because I had a good LSAT score. It ranked me, as I recall, at about the 95th percentile. I was very comfortable with the LSAT, and as a faculty member I participated in many admissions decisions based upon it. Then, during the course of my ten years in law teaching, there came a time when the average student in my class at the University of Chicago Law School had a higher LSAT score than I. I used to think about that as I stood before a class: “The average student out there has a better score than I.” That was when I began to think that there were other things as important as the LSAT score.

In a period of sharply increasing applications, BYU admissions policies admittedly pose a difficult challenge. But is this challenge any more difficult, and more insurmountable, than the challenge we face in sending nineteen- to twenty-one-year-olds, essentially unsupervised, to every nation, kindred, tongue, and people to preach the message of the restored gospel? With the inspiration of God we have found how to do that task tolerably well, and I suggest that by that same method we can identify the needed refinements in the BYU admissions criteria to serve our youth and support the mission of the Church.

Two of the problems I listed in my 1980 commencement address were really challenges. They are as important today as they were then. I will use them to conclude. One was titled “Effective Use of Resources”:

When we look at what our best predecessors accomplished with their scarce facilities, I wonder whether we as current teachers and researchers at BYU accomplish as much in relation to the splendid physical resources with which we operate? When we see what our best predecessors did in addition to their numerous teaching loads of 15 to 25 hours per week, are we accounting convincingly and productively for the greater time remaining after our much smaller teaching loads? When we see what our predecessors did with their scant opportunities to travel for professional development, I wonder if we are giving an adequate return in professional standing, scholarly output, and teaching excellence for the vastly increased professional development resources at our command.

The second challenge was titled “Boldness in Goals”:

Another challenge of the eighties—ironic in view of the constraints I have already summarized—is for us to be as bold as our predecessors. One of the remarkable things about our Mormon tradition is the boldness—even the audacity—of our pioneer grandfathers and grandmothers. They accomplished the impossible because they attempted the unthinkable. . . .

Our pioneer predecessors did not succeed in all they attempted, but their aspirations and their attempts were magnificent, and we have been blessed by the results. . . .

When we compare our opportunities and resources to those of our forebears, and when we compare what they undertook with what we undertake, I wonder if we set our sights high enough. In these terms there is surely nothing far-fetched about our stated goal of becoming a leader among the great universities of the world.

I appreciate the introduction that my good friend President Lee gave me. I appreciate the feeling that I have when I return to the campus.

None of us should say that all is well in Zion, and none of us should say that all is well at Brigham Young University. We have problems in 1990 like those we had in 1980. We’ll have problems in the year 2000, and we’ll continue to work with them. But what we must never do is lose sight of the purpose of the work we’re doing or the essential tie that we have to the Church in an institutional way and to our Heavenly Father in an individual way. If we lose that tie, we are trying to gain the whole world at the expense of losing our whole soul.

I don’t think that very many of us would advocate that, but I think it’s possible that some of us in our zeal to accomplish the things that we want to do in the university, which are good in and of themselves, will lose sight of the fact that in this university, with its unique governance and funding and stated mission, we must do things in a particular way. Part of that particular way is institutional, and part of it is individual in the way we approach our own tasks. I hope each of us will bear that in mind in the coming year and in all the years to come.

What each of us has as a testimony of our divine parentage and our eternal destiny is more important than any degrees that can be conferred from this podium or any honors that can be earned in this community. That is a profound eternal truth. This gospel, which gives us the purpose of life and the assurance of a Savior and compensates for the inevitable pains and transgressions and inadequacies of life, is the most precious thing that any of us have.

I testify to you of Jesus Christ, our Savior. I testify to you of his prophet, Joseph Smith, and of those in the line of succession that have led this Church and do lead this Church today. I assure you of the love of our Heavenly Father. He is mindful of every sacrifice and of every prayer. I give you this assurance and ask for the blessings of our Heavenly Father to be upon each of us in our separate responsibilities, in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Dallin H. Oaks was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this address was delivered during the BYU Annual University Conference on 28 August 1990.