I will describe nine expectations. I hope that each will be inspirational and challenging for students and teachers.

Imagine the emotions I feel as I stand before you, my fellow students. You have come by the thousands to hear me speak. More thousands of your parents, grandparents, and friends are present by television. You are here through loyalty and faith that I will give you something of value. I am humbled by your confidence and totally dependent upon our Father in heaven to make me equal to this responsibility.

I have felt impressed to speak to you about expectations—what you can expect from your teachers at BYU. As I proceed you will recognize that I am also suggesting what your teachers will expect of you. That is typical of BYU. Here teachers and students study together, worship together, and commit themselves to the same standards.

I will describe nine expectations. I hope that each will be inspirational and challenging for students and teachers. You will know that these expectations are not casual or incidental. Some are central to the mission of the university—any university. Others are unique to this University and its sister institutions in our Church’s Educational System. It is no exaggeration to say that these mutual expectations explain why we, teachers and students, have chosen to pursue our work at BYU.

Scholastic and Spiritual Preparation

1. First, you can expect your BYU teachers to be prepared, scholastically and spiritually. The doctor’s degrees held by more than 70 percent of the full-time teaching faculty represent many years of arduous and expensive preparation in the various academic disciplines. Our faculty have been through the shoals and have fought the current where you expect them to pilot you. Many have left very promising positions elsewhere to spend their lives here in your service. For your own sake and out of respect for what they represent, honor them with your careful attention and your best efforts.

Your teachers are also prepared spiritually. It is not an easy task for a teacher to be both rigorously professional and explicitly faithful, but that is our invariable expectation of them. They are challenged to bring the insights of the gospel of Jesus Christ into their subjects wherever possible, and in any case to share their personal testimonies of Jesus Christ. Your teachers represent a synthesis of scholastic excellence and spiritual strength, which is the goal we pose for you. As President Kimball reminded us last year:

. . . education on this campus deliberately and persistently concerns itself with “education for eternity,” not just for time. The faculty has a double heritage which they must pass along: the secular knowledge that history has washed to the feet of mankind with the new knowledge brought by scholarly research—but also the vital and revealed truths that have been sent to us from heaven. . . . Your double heritage and dual concerns with the secular and the spiritual require you to be “bilingual.” As LDS scholars you must speak with authority and excellence to your professional colleagues in the language of scholarship, and you must also be literate in the language of spiritual things. We must be more bilingual, in that sense, to fulfill our promise in the second century of BYU. [“Second Century Address,” (Provo: Brigham Young University Publications, 1975), pp. 1–2]

As BYU students you are also prepared. We are proud of your qualifications and your performance. I will give an example of each.

In the eight years from 1967 to 1975 the mean high school grade point average of our entering freshmen has remained solidly in the B range. Our freshmen’s mean ACT Score has remained constant in this period, while the national average has dropped significantly, more than one point. What does this mean? In the fall of 1975 our entering freshmen had national test scores that averaged in the seventy-fourth percentile of all college-bound students in the nation. These are very satisfying levels for a university that admits more than six thousand freshmen and has made no attempt to increase its admissions standards to become an elitist institution. The conclusion: Our students are well qualified for university studies.

How about our students’ performance in their studies? There are no better comparative evaluations of college seniors at various universities and colleges than their average scores on the law school and medical school admissions tests, which are general preparation tests given to thousands of students nationwide. We are proud to note that the average performances of BYU seniors are solidly above the national averages. We are behind the levels posted by the seniors at the most prestigious small private schools, but well ahead of institutions of comparable size, nationwide. Especially heartening is the fact that our students performances show steady increases from year to year on these revealing national tests.

Proper Example

2. Second, you can expect your BYU teachers to set a proper example. At BYU this means more than a proper example in a faculty member’s professional discipline. It includes being a worthy example in faith, in church activity, in family life, in the community, and in every other aspect of life. You should not expect perfection in your teachers, but you are entitled to expect—and I believe you will see—that each is trying to be a role model in all of these areas. When you see BYU faculty members struggling to meet their teaching commitments, fulfill their church callings, raise their families, and still make a contribution to their profession and their community, be aware that the example they are trying to set is not easy, even for them. Remember their example when they ask something of you that is not easy either.

Personal Concern

3. Third, you can expect your teachers to be concerned about the personal conduct and appearance of their students. At BYU we believe that character is more important than learning. All who enroll at BYU sign a solemn covenant to observe all of the principles of our Code of Honor and our Dress and Grooming Standards. Our teachers and other workers are committed to the same standards. The observance of these requirements is a matter of honor. Persons in violation have broken a promise.

Since we are vitally concerned about teaching integrity, each BYU teacher needs to remind and counsel students about commitments that are obviously not being fulfilled. You should therefore expect your teachers to speak to you in the classroom and elsewhere on campus if you are in violation of the Dress and Grooming Standards. For men that means, among other things, no long hair, beards, or grubby clothing. For women that means no skirts of immodest length, and no blue jeans or grubby attire.

A recent poll suggests that almost half of the students at an eastern university had cheated on exams. Our teachers will not condone any cheating, and neither will our students. It is part of our teaching mission to abolish dishonesty in the academic environment and elsewhere.

Because the issue is honesty and our intention is to teach it, teachers who after appropriate warning exclude students from their classes or examinations when they have reneged on their commitments, such as by flagrant dress and grooming violations or by cheating or copying someone else’s written work without proper credit, are perfectly within their teaching function as we perceive it.

Your teachers will encourage you to meet all of your commitments: to pay your debts, including student loans, to make full disclosure of all relevant facts when questioned, to be honest in identifying the source of your written work, and to be considerate of others, especially in study activities in the library or apartment.

I will illustrate BYU teacher and student concerns with character by four examples from my own experience.

A few years ago I taught a Book of Mormon class where students were invited to complete a workbook for extra credit or to offset a low examination grade. One fellow handed in a workbook that I saw to be in the handwriting of two different persons. The semester had concluded so I wrote the student for an explanation. No reply. In two months I wrote again. Still no reply. Over two years later he came to my office. He sadly confessed that he had, indeed, submitted work partly done by a friend. He hadn’t answered my letters since he had been in the mission field, and had been too ashamed to respond. Now he wanted to confess his sin and make restitution. He should have done so earlier, he said, since this had bothered him through his entire mission. I lowered his grade from C to D, told him how he could take the course over to raise his grade, congratulated him on facing up to his mistake, put my arm around him, and wished him well. Was I too severe in lowering his grade? I don’t think so. The principle of honesty was more important to both of us than the course or the grade. A low grade or the necessity to repeat the course was a suitable vindication of that principle, and the lesson taught by that sequence of events may be more important to that young man than any other lesson he learned that year.

A young woman who had learned that lesson wrote me some time ago to confess that she had falsely represented to a BYU teacher that she had read a required book when she had not. “I am in the LTM now,” her letter reads;

I find I must get this off my mind so I can learn as I should. I am only sorry that my actions make this letter necessary. I ask your forgiveness and that of the entire student body. I wish I could tell them that theymust be honest with themselves and their teachers, and make them understand why.

My third example involves a letter I received from a student who wanted advice. When he was a freshman he had been arrested and convicted of a minor crime. After he completed a successful probation his court record was removed and destroyed. Now he wanted to go to law school. How should he answer the invariable question on all law school application forms: “Have you ever been arrested?” A truthful “yes” might keep him from realizing his dream to attend law school. Karl G. Maeser, the founding genius of BYU and one of its greatest teachers, told his students that sooner or later everyone of them “must stand at the forks of the road and choose between personal interests and some principle of right” (Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years, 1:591). As you would expect, I advised this student to make full disclosure of his earlier arrest, facing it at this point rather than answering dishonestly and having to bear the guilt of concealment and the risk of disclosure all his life. A year later he wrote me as follows:

I decided to take your advice and I made full disclosure on the law school application, and instead of facing a possible expulsion from a law school and a ruined career and, as far as that is concerned, a ruined life, I chose a hard route, but it’s my pleasure to inform you that I was accepted into a law school. It was difficult at first to tell this truth, but I don’t think words can express what has happened.

My fourth example also involves a letter, which illustrates the very high standards of honesty among BYU students. The writer had worked on a campus job a year earlier.

I must admit [he explains] that while I was employed by BYU I was not completely honest in my dealings. I am afraid that I “goofed-off” while at work (visiting with fellow workers, etc.) I don’t feel that I worked sufficiently to merit the pay that I received. To me it seems that I stole that extra pay and I want to return it.

Figuring that he had wasted one hour each day for six months, the writer enclosed his check for the full amount, $273.60! Where but at BYU would that happen!

Our students and our teachers do care about honesty, and about facing up to mistakes and rising above them. We believe in eternal growth and you can expect your teachers to attach prime importance to the spiritual values upon which it is based.

Truth

4. Fourth, you can also expect your teachers to be direct about the truth. We have true academic freedom at BYU. Here we are free from the legal restrictions that put religious faith and insights off-limits to tax-supported colleges and universities. We are also free from the artificial neutrality on many moral values that hamstrings all public and most private colleges and universities. We are free to speak of what we know by the testimony of the Holy Ghost, as well as the theories we propound on the basis of observation and the scientific method.

We teach theories, for your education obviously demands them, but we also teach revealed truth. In the hands of a capable and skilled teacher the combination achieves the ultimate in academic freedom. We can come directly to the truth when the truth is known. That is liberating. As the Prophet Joseph Smith said in a sermon in Nauvoo, “I can never find much to say in expounding a text. A man never has half so much fuss to unlock a door, if he has a key, as though he had not, and had to cut it open with his jack-knife” (Documentary History of the Church, 5:423). Our teachers need not whittle away at contested theories, pretending they do not know what God has revealed, such as, for example, that abortion is sinful, that sexual relations outside the bonds of marriage are destructive to the human soul, that repentance is available and can lift us out of our suffering and degradation, and that men and women are the children of God on an eternal journey whose designed purpose is to attain, as the Bible says, “the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ” (Ephesians 4:13). These principles affect our attitudes and studies in many disciplines in this University. Our concern with revealed truth also prompts our teachers and students to approach their responsibilities prayerfully. With teachers who are praying to teach the truth and students who are praying to learn it, we have the most favorable possible conditions for knowing the truth.

We take pride in that fact, and because we are explicit about the ideals and goals of the University, which include the strengthening of religious faith and practice, our accomplishments are honored by our colleagues and sister institutions of higher learning, as was evident from the very favorable report we received from an outside team of scholars during our ten-year accrediting visit last spring.

Breadth of Education

5. You can also expect your teachers to be concerned about the breadth of your education—not just in their particular discipline, but all of the knowledge and skills expected of a university-educated person. Our new general education program is a major step toward improving the excellence of our offering.

Our forum assemblies are also an integral part of our general education effort, just as our devotional assemblies and first-Sunday firesides are an integral part of our religious instruction. I urge each of you—just as I expect your teachers to urge you—to attend every forum and devotional. Be here in the Marriott Center each Tuesday at 10:00 a.m. The devotional speakers are usually General Authorities. The forum speakers are carefully chosen for the excellence of their presentation and the breadth and general interest of their topics.

Most of you have had the experience of receiving a spiritual witness and other inspiration from the Holy Ghost while listening to a devotional speaker. Something akin to that can occur when our minds are stimulated by a fine lecture on a secular subject, especially one of broad general interest somewhat removed from our specialized pursuits. Ideas cultivate the mind, as a farmer turns the soil. Our intellectual harvest in selective areas will improve as we stimulate our minds generally.

One of the most important marks of an educated person is the ability to communicate in writing. Your ability to write clearly and succinctly is a concern of every professor in the University. Each faculty member has been asked to help raise the level of written expression by BYU students. Do not be surprised if your teachers in every discipline hold you to high standards of written expression. For your sake, every class where you submit written work should be an English class. The commonest complaint that graduate schools and employers make about the graduates of modern colleges and universities is that their written work is not acceptable. We hear these complaints about some BYU students also. In fact, this may be a particular Mormon weakness. From our youth we are given opportunities to speak in Church gatherings, and most of us become pretty articulate—perhaps even glib—by the time we reach college age. But give us a pen instead of a microphone, and our communication skills are immediately seen to be deficient.

Challenges for Excellence

6. Sixth, expect your teachers to be concerned that you do the best that you can in whatever you undertake: your church work, your family life, your personal financial management even your social life, and of course your other classes as well as your classes with them. Karl G. Maeser told his students, “Don’t be a scrub.” That word may not be familiar to you. A “scrub” is something inferior or insignificant. In the case of a person it is one whose growth is stunted through lack of effort, shortage of determination, or absence of high standards. Our BYU teachers are still saying, in effect, “Don’t be a scrub.” Heed their advice. Rise to the best that is in you. The vision and efforts and contributions of hundreds of thousands have united to give you the opportunities you enjoy at BYU. You are false to their trust if you fritter away your time or let yourself be satisfied with a mediocre effort. Here is what President Kimball said of this:

It is a privileged group who are able to come here. . . . [They] have an even greater follow-through responsibility to make certain that the Church’s investment in them provides dividends through service and dedication to others as they labor in the Church and in the world elsewhere. [“Second Century Address,” p. 10]

Challenges for Independence

7. Seventh, expect that your teachers will also encourage you to think for yourself. They will not appreciate a “sponge” who thoughtlessly sops up the whole flow of text and lecture in anticipation of squeezing it back onto the examination paper without a droplet of absorption into the dry recesses of the brain. Pump your textual material and class lectures and discussions through the filter of your mind. The equivalent responsibility for the teacher is to see that students are not burdened with mere storage functions or busywork unrelated to the involvement of the mind. The greater the students’ effort on a particular assignment, the easier it should be for the teacher to justify its educational purpose.

The attainment of an education is not so much the acquisition of a body of knowledge as the development of the ability to think—to evaluate information and to translate knowledge into wise action. That view of education sees the student as the key participant in the process, not as a compliant memory bank for data retrieval. Only with your active involvement in learning can BYU students and teachers meet President Kimball’s challenge:

It ought to be obvious to you, as it is to me, that some of the things the Lord would have occur in the second century of BYU are hidden from our immediate view. Until we have climbed the hill just before us, we are not apt to be given a glimpse of what lies beyond. The hills ahead are higher than we think. This means that accomplishments and further directions must occur in proper order, after we have done our part. We will not be transported from point A to point Z without having to pass through the developmental and demanding experiences of all the points of achievement and all the mile-stone markers that lie between![“Second Century Address,” pp. 9–10]

Frank Evaluation

8. Eighth, you can expect your teachers to be explicit and forthright in describing your shortcomings. A teacher who rewards an average performance with a mark of distinction is false to the trust of his or her students. Evaluations are the signposts and milestones on the road of growth. Inaccurate markers can only lead us to a wrong destination or persuade us to rest complacently in the shade of a mediocre valley when we are still a far journey from the summit of excellence.

If you wonder how Brother So-and-so or Sister So-and-so could have been so hard on you when they are a brother or sister in the gospel, understand that they pay you their highest compliment by explicitly recognizing when you have not measured up to your possibilities and by forthrightly advising you of it. Our teachers should not and will not indulge in erroneous of shabby effort, and you should not expect them to do so, certainly not for the sake of a brotherhood or sisterhood in the gospel of the Master Teacher who has told us that those whom he loves he chastens and corrects (see Proverbs 3:11; D&C 95:1).

Though I still cringe to recall their disclosures of my inadequacies, I place the highest value on the teachers who have not indulged me with undeserved praise or misleading silence, but have given me a chance to be saved by honest criticism. I will give two examples.

When I was a law student I was handicapped by a self-satisfied assurance that I could write verse even though I had never been schooled in that discipline. A classmate and I entered a poetry-writing contest sponsored by three law professors who knew something about the subject. In this naive collaboration, my friend was to provide the rhymes and I was responsible for the meter. Our lengthy effort of fifteen or twenty stanzas attempted to describe and poke fun at a recent judicial opinion by a renowned judge, to whom we sent a copy of the finished version. Though our poem didn’t win a prize, or even a favorable mention, I still thought we were the cleverest poets in the school. Proceeding on that assumption, I sought a compliment from one of the faculty judges by reminding him of our effort, telling him we had sent a copy to his friend the judge, and asking him if he thought the judge would be offended at our poem. His reply told me where I stood as a poet and probably saved me great subsequent time and embarrassment. “Oh, no, he won’t be offended,” the professor replied thoughtfully, “not unless he has a good sense of meter.”

On another occasion I recall how Edward H. Levi, now attorney general of the United States but then my law school dean and teacher in an anti-trust course, rebuked me publicly for being unprepared in class. In classroom discussion he asked me to distinguish between the legal basis of decision in two complicated anti-trust cases. When I fumbled momentarily—revealing to his practiced eye that I was not completely prepared—he cut me down with a single remark: “Never mind, Oaks, you have to be good to answer that question.” He never found me unprepared again, from that day to this. Some years later Edward Levi appointed me to his faculty, and later made me acting dean. Today he is a valued friend and colleague, but most of all I esteem him as my teacher. I will always be indebted to him for a lesson that would have gone untaught if he had let sympathy or misplaced goodwill interfere, with a teacher’s responsibility to remind a student who was not measuring up to a potential. The reminders will probably be kinder at BYU, but if your teachers are so kind that they fail to make their point or let you miss it, they will not be serving you well. Jacob gave us a vivid example of this principle of correction in a religious context when he spoke these words to the people of Nephi:

Behold, if ye were holy I would speak unto you of holiness; but as ye are not holy, and ye look upon me as a teacher, it must needs be expedient that I teach you the consequences of sin. [2 Nephi 9:48]

Kindness and Love

9. Ninth and finally, the BYU teacher will be kind and loving. At times that will be his or her greatest challenge, since students, I think you will concede, can sometimes be very difficult. Sometimes our resistance to knowledge is directly proportional to our ignorance. The less we know, the more we resist knowing, until some kindly teacher succeeds in planting the idea that there may be something to learn from that book or that lecture.

In this connection teachers of literature may appreciate, and perhaps students of literature will benefit from, Schopenhauer’s clever criticism of students who reject a great written work without investing the effort to understand it. “Works like this are as a mirror,” he said, “if a jackass looks in you cannot expect an angel to look out” ; and again, “when a head and a book come into collision, and one sounds hollow, is it always the book?” (W. Durant, The Story of Philosophy, 12th printing, 1953, p. 221).

Many of our best teachers will not brand ignorance publicly or even privately to the person involved. Instead, they will hold up the standard of knowledge so vividly that their students will measure themselves against it, reach a correct conclusion, and direct efforts at improvement with a minimum of embarrassment. Such an effort takes consummate skill, but it is motivated by love.

Fortunately most students are lovable, and sometimes the most ignorant are the most lovable. Consider the unsuspected plight of the ignorant but lovable missionary who wrote his own letter of recommendation for admission to the University a few years ago. He called it a “self recommendation” :

I’m really proud of [so-and-so, he wrote, giving his own name] for the tremendous progress he has made these past few years, not only in self disapline [sic] and controal [sic] but in the phenominal [sic] growth he has made through maturity sense [sic] being out here serveing [sic] the Lord. Our Father in Heaven has really taken him in hand, now that hard and rough stone is no more, but is a smooth polished shaft in the quiver of the hands of the Lord. To better describe [so-and-so] and tell you how much he has progressed in order for you to accept [him] into the University let me for a moment tell you how much he has progressed. Let me tell you how teachable he is [and so on].

Our BYU teachers teach with the principle of love. I felt that love as a student and it warmed me and encouraged me to try things I had not even dreamed possible. One of my teachers who epitomized love for students and who is still on our faculty is Professor Stewart L. Grow of political science like hundreds of his other students I felt his interest and concern for me so keenly that I reported my activities to him every year after I graduated, by letter or personal visit when I was in Provo. That kind of loving relationship, which is available with BYU teachers, will endure for eternity.

That loving and teaching relationship can also be enjoyed in BYU employment, where many of our students receive some of their most valuable lessons. One of our most memorable teachers in years past was B. T. Higgs, superintendent of buildings and grounds, who held short teaching sessions on honesty and other admirable traits with students who were working their way through school as part-time custodians. He and his boys would meet at 5:00 a.m. on lower campus before they began their work. In truth, every BYU worker is a teacher for good or ill, and we attach great importance to the informal curriculum that is taught by association with BYU personnel outside the classroom.

“The more I have seen of teaching,” President Harold B. Lee once said in a reference to the elementary grades, “the more I think that this is the great demand upon those who teach our children. You love them and teach them to love you, and I will take a chance on the outcome of your instruction” (Stand Ye in Holy Places, pp. 296–97). The principle is no less true in the University, and we are proud of the fact that the spirit of love has always ennobled the relationship of teacher and student at Brigham Young University.

I will close with some of the words President Kimball spoke in his dedicatory prayer for the Centennial Carillon Tower, whose music is refining our second century. His prayer on that day is our prayer on each day of our lives in this great University:

Father, we thank thee for this institution and what it has meant in the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and their posterity, for the truths they have learned here, for the characters that have been built, for the families which have been strengthened here . . . Just as these bells will lift the hearts of the hearers when they hear the hymns and anthems played to thy glory, let the morality of the graduates of this University provide the music of hope for the inhabitants of this planet. [“Second Century Address,” p. 12]

The means of fulfilling that challenge are open to every teacher and every student at BYU. May we use those means and fulfill our responsibilities, is my prayer, which I give to you as I bear my testimony of the truthfulness of the gospel and of the divine calling of our leaders, in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

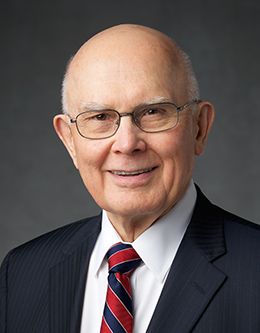

Dallin H. Oaks was president of Brigham Young University when this devotional address was given on 31 August 1976.