We must strive for mutual understanding and treat all with goodwill. We must exercise patience. We should all speak out for religion and the importance of religious freedom. We must, above all, trust in God and His promises.

I am pleased for the opportunity to speak at this BYU devotional. The first BYU devotional I addressed was exactly forty-five years ago, in 1971. That audience included my oldest daughter, just enrolling as a freshman here. Many years later I spoke at this devotional assembly to an audience that included several of my grandchildren. Today this audience includes our oldest great-granddaughter, a sophomore here. Time goes on.

I.

This opportunity comes at a unique time. I am the only General Authority assigned to address this BYU audience between the beginning of school this fall and the election on November 8. And this audience includes thousands who will soon have their first opportunity to vote. I, therefore, begin by speaking about our national and local elections.

The few months preceding an election have always been times of serious political divisions, but the divisions and meanness we are experiencing in this election, especially at the presidential level, seem to be unusually wide and ugly. Partly this results from modern technology, which expands the audience for conflicts and the speed of dissemination. Today, dubious charges, misrepresentations, and ugly innuendos are instantly flashed around the world, and the effects instantly widen and intensify the gaps between different positions. TV, the Internet, and the emboldened anonymity of the blogosphere have facilitated the current ugliness and have replaced whatever remained of the measured discourse of the past. Nevertheless, as the First Presidency always reminds us, we have the responsibility to become informed about the issues and candidates and to independently exercise our right to vote. Voters, remember, this applies to candidates for the many important local and state offices as well as the contested presidential election.

II.

We should also remember not to be part of the current meanness. We should communicate about our differences with a minimum of offense. Remember this teaching of the Prophet Joseph Smith:

While one portion of the human race [is] judging and condemning the other without mercy, the great parent of the universe looks upon the whole of the human family with a fatherly care and paternal regard; he views them as his offspring, and without any of those contracted feelings that influence the children of men.1

I spoke about this subject two years ago in an October general conference talk titled “Loving Others and Living with Differences.” My message focused on doctrine and its application to the differences we face in our diverse circumstances in Church and family and in public, but the principles I taught are also relevant to political differences. I said:

We are to live in the world but not be of the world. We must live in the world because, as Jesus taught in a parable, His kingdom is “like leaven,” whose function is to raise the whole mass by its influence (see Luke 13:21; Matthew 13:33; see also 1 Corinthians 5:6–8). His followers cannot do that if they associate only with those who share their beliefs and practices. . . .

[The Lord also taught that] “he that hath the spirit of contention is not of me, but is of the devil, who is the father of contention, and he stirreth up the hearts of men to contend with anger, one with another” [3 Nephi 11:29]. . . .

Even as we seek to . . . avoid contention, we must not compromise or dilute our commitment to the truths we understand. We must not surrender our positions or our values. . . .

[In] public discourse, we should all follow the gospel teachings to love our neighbor and avoid contention. Followers of Christ should be examples of civility. We should love all people, be good listeners, and show concern for their sincere beliefs.2

Today, I say that if the Church or its doctrines are attacked in blogs and other social media, contentious responses are not helpful. They disappoint our friends and provoke our adversaries.

Finally, as I said two years ago:

When our positions do not prevail, we should accept unfavorable results graciously and practice civility with our adversaries.3

III.

In the distressing circumstances that surround us, we must trust in God and His promises and hold fast to the vital gospel teaching of hope. The prophet Nephi taught that we must “press forward with a steadfastness in Christ, having a perfect brightness of hope, and a love of God and of all men” (2 Nephi 31:20). Later, the apostle Paul told the Corinthians:

We are troubled on every side, yet not distressed; we are perplexed, but not in despair;

Persecuted, but not forsaken; cast down, but not destroyed. [2 Corinthians 4:8–9]

When we trust in the Lord that all will work out, this hope keeps us moving. Hope is a characteristic Christian virtue. I am glad to practice it and to recommend it to counter all current despairs.

Hope based on trust in the Lord and His promises has sustained me through all the circumstances of my life. For example, when I approached my first enrollment at BYU, sixty-six years ago, the Korean War had just begun. I had just celebrated my eighteenth birthday, and my Utah National Guard field artillery group had just been alerted to join the war in Korea. Two of our battalions had already been mobilized and sent to training locations in the United States. Only the group headquarters here in Provo, to which I belonged, had not yet received its mobilization orders. We were expecting to be sent any day.

As we waited, it came time for freshmen to enroll for the fall quarter at BYU. What should I do? I decided to enroll, pay tuition, start school, and trust in the Lord for whatever happened. If my unit was mobilized, I would leave. If not, I would at least be proceeding forward with my education. Incidentally, the total enrollment at BYU that quarter was only 4,500 students4 and the tuition and fees were only $45.5 As it turned out, our small headquarters group was never mobilized, so I continued and completed my formal education.

Every generation has challenges that can cause discouragement in those without hope. The future is always clouded with uncertainties—wars and depressions being only two examples. While some abandon progress, you of faith should hope on and press on with your education, your lives, and your families.

Some years ago President Thomas S. Monson gave this valuable counsel:

My brothers and sisters, today, as we look at the world around us, we are faced with problems which are serious and of great concern to us. . . .

My counsel for all of us is to look to the lighthouse of the Lord. There is no fog so dense, no night so dark, no gale so strong, no mariner so lost but what its beacon light can rescue. It beckons through the storms of life. The lighthouse of the Lord sends forth signals readily recognized and never failing.6

Those words comfort me as I view the terrible conflicts in today’s world and the extreme moral and policy divisions that separate different citizens and different aspiring leaders. We all should rely on this assurance in modern revelation: “Fear not, little flock; do good; let earth and hell combine against you, for if ye are built upon my rock, they cannot prevail” (D&C 6:34).

With faith and hope, and with God’s help, we will prevail against our challenges. As Elder Kim B. Clark told your teachers and leaders a few weeks ago, BYU and its values are under attack. We are all being asked to do hard things, for which we need “greater faith in the Lord Jesus Christ,” who “will open doors that are closed. He will inspire and guide and provide. He is in charge.”7

IV.

I now speak of one of the challenges that face us: the meaning and application of the vital constitutional guarantees that government authority shall make no laws or regulations “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble.”8 Those rights are fundamental to our constitutional order—not just to protect citizens against repressive government action but also to foster the cherished open society that is the source of our freedom and prosperity. Beyond that, the free exercise of religion is vital because it insures citizens the rights of worship and action that are fundamental to their being.

For many years I have paid close attention to the social and legal trends that are likely to affect the fundamental guarantees that are so vital to fulfill our Church’s mission and to accomplish BYU’s educational mission. I am convinced that a worldwide tide is currently running against both religious freedom and its parallel freedoms of speech and assembly.9

I believe religious freedom is declining because faith in God and the pursuit of God-centered religion is declining—worldwide. If one does not value religion, one usually does not put a high value on religious freedom. It is looked at as just another human right, competing with other human rights when it seems to collide with them. I believe the freedoms of speech and assembly are also weakening because many influential persons see them as colliding with competing values now deemed more important. Some extremists have even opposed free speech as an obstacle to achieving their policy goals.

V.

In our current cultural and political atmosphere, we are distressed to see official and private infringements on free speech, free association, and the free exercise of religion that pose threats to our free and open society. While a political party in power at the federal or state level has greater potential to sponsor official threats, such threats can also be made by others.

Most of the examples I will give are in higher education, but comparable examples could be given in the broader society, including the media, the arts, business, politics, and other areas of culture. I have chosen to concentrate on higher education, since these examples are most appropriate for discussion with a university audience at BYU. Free speech has always been highly valued in education, but open inquiry and communication are currently being replaced on too many campuses by a culture of intellectual conformity and the silencing or intimidation of opposition. This culture even includes formal or informal punishment of those with political views not currently in favor.

As I provide my list of examples, I invite you to augment or challenge these with observations of your own. Weigh the whole and reach your own conclusions. As you do, note the close relationship between the free exercise of religion and the associated rights of free speech and freedom of assembly.

1. Earlier this year a group in the California legislature sought to deny state funding to students of private colleges and universities that rely on religious exemptions from Title IX non-discrimination requirements. Fortunately that effort was blocked, but it will return next year.10 Title IX is the same federal statute that was sought to be used to force BYU to have coed dorms when I was president forty years ago.11 BYU prevailed in that earlier contest, but in today’s political climate, such attempts to override the freedoms of religious colleges seem certain to continue.

2. A more common and more personal challenge to free speech in current policy debates is the labeling of opposition arguments as “hate speech” or “bigotry.” This kind of name-calling chills free speech by seeking to penalize the speech of opponents—personally, socially, or professionally. A legal scholar’s recent book, which advocates pluralism, mutual respect, and coexistence, states that the label “bigot” is a “conversation stopper” because it “attributes a particular [negative] motive to an action.”12 The author observed that this kind of labeling “frequently appears against religious believers and groups that maintain traditional beliefs about sexuality in their internal membership requirements.”13 Incidentally, my dictionary defines bigot as “a person who is utterly intolerant of any creed, belief, or opinion that differs from his own.”14 Who fits that description in this contest of motives and opinions?

3. Of greater concern are the institutionalized “free speech zones” established by some universities to provide a small designated space in which students may speak freely. The rest of the campus is then a restricted speech zone, in which certain words and ideas (including what are called “microaggressions”) are not to be spoken.15 Such general restrictions on campus speech seem unlikely to survive their current legal challenges. Academic freedom should not be limited to those who agree with prevailing political views. But the fact that some educators have succumbed to pressures to create such restrictions is worrisome.

4. Free speech and association are also chilled when campus pressures result in administrations canceling commencement speaking invitations or honors to persons whose prior actions or words are being attacked by faculty or students. Although institutions of course exercise judgment about whom to honor or invite, once invitations are extended, they should not be canceled just because a segment of campus is hostile to the honoree’s or speaker’s political views.

5. Consider another action of some state institutions. Students seeking official campus status for some religious, social, or political clubs have been told that they must not have any limitations on their membership or leadership. Campus organizations must “take all comers” and let them seek organizational leadership, even if they oppose the organization’s principles and standards.

6. A new and rising right being urged is the right not to be offended in the public square and on campuses. Consider how that alleged “right” would suppress religious teaching and free speech by giving any objector the right to police and control the communications of adversaries. Such a concept would also compromise the mission of universities. On that subject, we cannot doubt the wisdom of Clark Kerr, first chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley, and twelfth president of the University of California:

The university is not engaged in making ideas safe for students. It is engaged in making students safe for ideas. Thus it permits the freest expression of views before students, trusting to their good sense in passing judgment on these views. Only in this way can it best serve American democracy.16

7. In recent years, some scholars whose work has questioned or opposed majority thinking in their disciplines or contradicted the current dogmas of political correctness have faced dismissal or other academic sanctions or, in any event, have had difficulty having their work published in professional journals. Similarly, colleges and universities—especially religious institutions or those associated with conservative causes—are facing increasing pressures from some professional associations and accrediting bodies to conform. Less visible are the many reports of hiring decisions that discriminate against persons who hold or are presumed to hold unpopular views. These examples of discrimination to defend prevailing positions are almost impossible to prove, but their effect—evident in the faculty composition and in the hiring decisions of various academic departments and other organizations—makes them obvious to the critical eye.

8. Finally, I cannot refrain from citing the tactics of public shaming, boycotts, and other actions to punish opponents and intimidate further opposition. Such tactics, which our Church and its California members experienced during and after the Proposition 8 same-gender marriage referendum, obviously poison the atmosphere for open discussion and inquiry. Although often invoking the popular rhetoric of equality and rights, those who employ these tactics erode the vital protections of freedom of thought, speech, religion, and assembly and diminish our country’s beacon light of freedom to the world.

VI.

We are fortunate that there are leaders whose examples and words promote the values of freedom. Two years ago the leadership of the University of Chicago noted “recent events nationwide that have tested institutional commitments to free and open discourse.” They established a faculty Committee on Freedom of Expression, whose report has now been influential with other senior institutions. That report gave expression to such traditional ideas as these:

It is not the proper role of the University to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive. . . .

. . . The University’s fundamental commitment is to the principle that debate or deliberation may not be suppressed because the ideas put forth are thought by some or even by most members of the University community to be offensive, unwise, immoral, or wrong-headed. It is for the individual members of the University community, not for the University as an institution, to make those judgments for themselves.17

That report of course acknowledged that the university may restrict certain kinds of expressions, such as those that are illegal, defamatory, threatening, or harassment. Significantly, it also recognized restrictions on speech “that is otherwise directly incompatible with the functioning of the University.”18

As some universities continue to cave in to pressures for prohibition and academic censorship, I fervently hope that most will follow the principles stated in that persuasive Chicago report.

VII.

Some of you are wondering whether I will speak of how my concerns for freedom in higher education apply to BYU. I have obviously pondered deeply on that subject, especially during the nineteen years of my service in important positions of academic leadership, first at the University of Chicago and then at BYU. The similarities between those two great universities are far larger than their differences, but there are differences, which I will describe.

Both are private universities. Both must be free to pursue their separate declarations of mission and purpose and to define and advocate the freedom necessary to achieve them. Both are vital contributors to the valuable but threatened diversity of higher education in America.

The differences are rooted in BYU’s unique religious mission and the method of learning inherent in it. As stated in BYU’s official policy on academic freedom, dated more than twenty-three years ago, “The BYU community embraces traditional freedoms of study, inquiry, and debate, together with the special responsibilities implicit in the university’s religious mission.”19 Those special responsibilities include some limits on academic freedom. Limitations are common to all universities, as the Chicago report conceded, but BYU’s limitations are express and well publicized. Its policy states:

BYU defines itself as having a unique religious mission and as pursuing knowledge in a climate of belief. This model of education differs clearly and consciously from public university models that embody a separation of church and state. . . .

. . . Religion offers venerable alternative theories of knowledge by presupposing that truth is eternal, that it is only partly knowable through reason alone, and that human reason must be tested against divine revelation.20

In that context, BYU students commit to a code of honor that prohibits speech that is dishonest, illegal, profane, or unduly disrespectful of others. The limitations on faculty expression apply to expression that seriously and adversely affects the university mission or the Church. . . . Examples would include expression with students or in public that:

• contradicts or opposes, rather than analyzes or discusses, fundamental Church doctrine or policy; [or]

• deliberately attacks or derides the Church or its general leaders.21

Consider those limitations, which are closely related to BYU’s declared method of learning, and I believe you will conclude that BYU’s Academic Freedom Policy is correct when it says that “individual freedom of expression is broad, presumptive, and essentially unrestrained except”22 for these narrow limits. Indeed, in many ways, academic freedom at BYU exceeds that at many colleges and universities that pretend to have unqualified academic freedom and then apply or submit to the kinds of exceptions I described earlier.

BYU’s policy concludes with this important affirmation:

For those who embrace the gospel, BYU offers a far richer and more complete kind of academic freedom than is possible in secular universities because to seek knowledge in the light of revealed truth [and I would add by the methods of revealed truth] is, for believers, to be free indeed.23

VIII.

And so I have spoken of elections, hope, and freedom. In these distressing times our freedom and hope can best be fostered by five actions:

1. We must concentrate on what we have in common with our neighbors and fellow citizens.

2. We must strive for mutual understanding and treat all with goodwill.

3. We must exercise patience.

4. We should all speak out for religion and the importance of religious freedom.

5. We must, above all, trust in God and His promises.

I testify of the reality of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, and of the promise expressed by His servant Mormon, who said:

And what is it that ye shall hope for? Behold I say unto you that ye shall have hope through the atonement of Christ and the power of his resurrection, to be raised unto life eternal, and this because of your faith in him according to the promise. [Moroni 7:41]

In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

© by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Notes

1. Joseph Smith, “Baptism for the Dead,” Times and Seasons 3, no. 12 (15 April 1842): 759, punctuation modernized; quoted in Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2007), 404.

2. Dallin H. Oaks, “Loving Others and Living with Differences,” Ensign, November 2014, 25–27; emphasis in original.

3. Oaks, “Loving Others,” 27.

4. See table 2 in Brigham Young University Enrollment Résumé, 1963–64 (Provo: Office of Institutional Research, BYU, May 1965), 4.

5. See Brigham Young University Annual Catalog Issue: 1950–51 (Provo: BYU, 1950), 40, archive.org/details/annualcataloguei19501951brig.

6. Thomas S. Monson, “A Word at Closing,” Ensign, May 2010, 113.

7. Kim B. Clark, “The Lord’s Pattern,” BYU address given at university conference, 22 August 2016.

8. First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

9. See, e.g., “The Muzzle Grows Tighter,” Free Speech, The Economist 419, no. 8992 (4 June 2016): 55–58, economist.com/news/international/21699906-freedom-speech-retreat-muzzle-grows-tighter.

10. See Darren Patrick Guerra and Andrew T. Walker, “Religious Liberty Crisis Averted in California,” Public Discourse, Witherspoon Institute, 17 August 2016, thepublicdiscourse.com/2016/08/17628.

11. See, e.g., “BYU Receives Support on Stand Against Sex Bias Rules,” Ensign, February 1976, 79.

12. John D. Inazu, Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving Through Deep Difference (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 98, 99.

13. Inazu, Confident Pluralism, 98.

14. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language, s.v. “bigot,” 146.

15. See Peter Schmidt, “Speaker Beware: Student Demands Make Campus Speech a Minefield,” Special Reports, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 29 February 2016, chronicle.com/article/Speaker-Beware/235428.

16. Clark Kerr, remarks at Charter Day ceremonies, University of California, Berkeley, 20 March 1961; quoted by David Halligan in Letters to the Editor, The Economist, 25 June 2016, 16, economist.com/news/letters/21701088-letters-editor.

17. Laura Demanski, “Opening Inquiry,” University of Chicago Magazine, July–August 2015, mag.uchicago.edu/university-news/opening-inquiry.

18. Demanski, “Opening Inquiry.”

19. “Academic Freedom Policy,” University Policies, Brigham Young University, 1 April 1993, policy.byu.edu/view/index.php?p=9.

20. “Academic Freedom Policy.”

21. “Academic Freedom Policy”; emphasis in original.

22. “Academic Freedom Policy.”

23. “Academic Freedom Policy.”

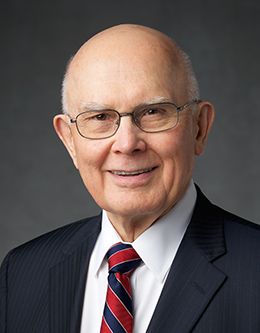

Dallin H. Oaks, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, delivered this devotional address on 13 September 2016.