Words, the power of language, are among the greatest gifts. I pray we can use words for our edification and bless the lives of others.

Good morning. I am happy to be here today, though I feel like the speaker in church who said she felt inadequate standing before the congregation. One sister said to another, “Isn’t she humble?” And the other responded, “That’s no real accomplishment, she has a lot to be humble about.”

Some of my students are sitting here thinking, “No joke!”

I do feel overwhelmed at the prospect of attempting to share something new and of value as I stand in the footsteps of the great men and women who have been here before me. I pray I can share some of my life and thoughts in a way that may help some of you have a new and useful perspective about words and their place in a Christ-centered life.

Words are my tools. As a librarian I collect, catalog, and preserve them. As a lawyer, which is my principal profession, I search them out, savoring the power, sound, feel, and nuance of them. As a mother, words are something I teach, and teach with—a method of motivation, reward, and reprimand. As a person of faith, they are second only to spiritual promptings as a form of guidance, comfort, and inspiration.

Lately, however, I have observed a distressing escalation of the use of words to hurt, anger, divide, and make war. Perhaps as a law professor I should approve of the trend. It does, after all, make well-paying work for many of our graduates. However, I have viewed myself as a solver of problems and a peacemaker, not as a warrior. I have not found entertainment in L.A. Law or its more recent progeny. Neither am I comfortable with the wars of words that rage around us.

Today I would like to talk about the power of words. I would like to remind you of some of their magic. There is nothing arcane about words. They are not supernatural. They are like light and gravity—they are central to our existence, and, because they are pervasive, we often fail to see them or recognize their power and worth.

John sets us on the right path:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

The same was in the beginning with God.

All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. [John 1:1–3]

The Savior is the Word. Let us consider whether our words are worthy of Him.

Words are among the most marvelous gifts we have as human beings. Words are tools used by God to build the necessary framework to lift us from our mortal existence and carry us back to His presence. He uses words for making and keeping binding commitments. The difference between an eternal marriage and a marriage of degrading cohabitation is a few words.

This is made clear in one of the most loved films of the BYU community, past and present:

Buttercup: Oh, Westley, will you ever forgive me?

Westley: What hideous sin have you committed lately?

Buttercup: I got married. I didn’t want to. It all happened so fast.

Westley: Never happened.

Buttercup: What?

Westley: Never happened.

Buttercup: But it did. I was there. This old man said “man and wife.”

Westley: Did you say “I do”?

Buttercup: Uh, no. We sort of skipped that part.

Westley: Then you’re not married. If you didn’t say it, you didn’t do it.

[From the movie script for The Princess Bride, http://www.krug.org/scripts/princess_bride.html]

Our words in the marriage vows, and those of the priesthood-holding sealer who binds us together for eternity, are not symbols of the marriage. Words are the mechanism for making the vows and for our Father’s accepting our commitment and granting us the opportunity to extend those vows into eternity. The vows are the wedding—the binding.

As we bind ourselves to our eternal companions through vows, we also bind ourselves to God. We are members of a covenant church. We enter into covenants with our Father in Heaven, as did Abraham, his son, and his grandson. Our Father makes great promises to us through those covenants: eternal life, eternal marriage, blessings poured from the windows of heaven. “I, the Lord, am bound when ye do what I say; but when ye do not what I say, ye have no promise” (D&C 82:10).

The individual covenants we make are set out in specific sacred words. The baptism prayer, the sacrament prayer, and portions of the prayer of confirmation use precise words. Why must a baptism or sacrament prayer, a sealing prayer, or any other prayer or blessing in the temple be witnessed and spoken exactly as it is set out in scripture or otherwise revealed? Because the exact pattern of those words is a sacred act—an ordinance—an exercise of the priesthood of God. If you didn’t say it, you didn’t do it.

Used in the context of our relationship with God, words are real, and their power is real. Repentance can be real and sincere, but our acceptance of the Atonement is not sufficient if we only have a change of heart. We must also be baptized. The act, and the words of the prayer, are more than symbols. They effect real change. The acceptance and understanding of that change is part of the act of repentance and of our preparation for baptism. Contemplating those vows enables us to test the reality of our commitment to repentance, to a forsaking of past sins and a covenant to take upon ourselves the name of Jesus Christ—more words. More words that are the acts we cherish and revere (see D&C 76:50–54).

As a lawyer, I understand that. Mutually enforceable promises to act or pay constitute a contract. One relying upon the representations or promises of another can legally bind the promisor. The promisor cannot change his mind or say, “King’s X, I didn’t really mean it.” The time of agreement may alter tax liabilities or the validity of the agreement itself. The parties cannot lawfully misrecord the time or date when it is an element of the agreement. The law views those words as binding, just as our Father does in the spiritual context.

For this reason I am always shocked when I learn of a law student or lawyer who blithely alters the facts recited in an agreement. He has not made a legally valid change but has committed fraud—deception with intent to achieve a benefit to which the client is not legally entitled. If caught, he will suffer the appropriate penalties—think Enron. If not, he remains at risk of discovery. The false words may fool some people, but they do not make an invalid document valid. If we lie in a document, can we expect the courts to honor the document?

However, we are mortal and can be deceived. It is possible that the liar can cover up a lie, and it will live so long that it is accepted as truth and the law does not allow the question to be reopened. That does not make it true, but it takes the lie beyond the power of the court to undo its consequences. The term for this isstatute of limitations. It means a limitation of action: the services of the courts are no longer available to a petitioner who seeks to overturn a result based on the lie. The law provides for a limitation of actions because otherwise there would be no certainty in our temporal lives. Contracts, deeds, and other transactions would never be final. It would be impossible for us to have certainty in our temporal affairs.

Temporal affairs are reciprocal of eternal ones. In an eternal world, with an immortal Father and omniscient judge, we cannot lie. We can say we have repented and been baptized, but if we do not in our hearts make the covenants that go with the words, can we expect our Father to honor them? We can fool ourselves, our bishops, our mission presidents, and our spouses, but we cannot lie to our judge, our Father. It is not an accident that Satan is known as the father of lies:

And because he had fallen from heaven, and had become miserable forever, he sought also the misery of all mankind. Wherefore, he said unto Eve, yea, even that old serpent, who is the devil, who is the father of all lies, wherefore he said: Partake of the forbidden fruit, and ye shall not die, but ye shall be as God, knowing good and evil. [2 Nephi 2:18]

On the other hand, our Father is the Father of Truth.

I have a personal vision, not a comfortable one, of the Judgment. I think the book that is the record of each life is the heart and mind of the person. Judgment is ultimately a stripping away of all lies. We are faced with our own selves, the absence of all deceit, excuse, rationalization, or obfuscation. Further, we know that our Father and our Savior have a perfect knowledge of us, as we now have. They love us anyway. However, they also know the exact degree of our sin, our repentance, and our acceptance of the proffered Atonement. Stripped bare of all pretense, we are not so much judged as we come to fully understand the justice, the mercy, and the inevitability of our ultimate fate.

Until that day we must live with an imperfect knowledge of the truth of words. So I will turn from the perfection of words and understanding to which we come in the next life to the more difficult, even trying confusion we bring to each other as we use and misuse words each day.

I want to talk about the mundane uses of words for the rest of our time together because their consequences are not mundane. I think these uses are the ones that get us into the most difficulty. In our daily speech we use words casually. We toss them out, sometimes careless of their effect. We drum up a phrase for its immediate impact without thinking of its long-term consequences.

My father would not tolerate a vulgarity, much less an obscenity or profanity, to be used in the home or by his children. Once, when I was about 11, I used a word often used by my friends and classmates and also used, though not in my father’s presence, by my siblings. It was a mild expletive, one that had once had a specific biological connotation, lost through millions of thoughtless repetitions. He asked, in the disappointed tone that always stirred the guilt I was carefully trying to ignore, if I was so bereft of imagination that I couldn’t think of a creative way to express myself. He was disappointed if my education from my parents had left me so stunted in vocabulary that I could find nothing to say of greater grace or meaning.

My parents and their siblings were pioneers. As an adult I had the occasion to read the journals and autobiographies of other late 19th- and early 20th-century settlers as well as historical novels, including my favorite, The Virginian, which tells the story, thinly disguised, of the in-laws and grandparents of some of my dearest friends. Most of these men and women had a few years of education in a local schoolhouse or home. They lacked degrees or academic distinction. However, it was central to their self-definition that they expressed themselves well. Their stories were works of art. Their descriptions were careful and precise. In The Virginian the protagonist brings a train car full of cowboys on the verge of rebellion into happy, though abashed obedience by selling them as truth a tall tale of such magnificence that they bow to his obvious superiority. (See Owen Wister, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains,http://xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/wister/ch16.html.)

My relatives of the same generation viewed speech and especially storytelling as entertainment, art, and a way to build and maintain subtle and nuanced relationships of love and respect within the family and the community. Many of the stories were funny, many tender, but the art of well-chosen language was a hallmark of intelligence and leadership. Or, as Elder Dallin H. Oaks said:

A speaker who mouths profanity or vulgarity to punctuate or emphasize speech confesses inadequacy in his or her own language skills. Properly used, modern languages require no such artificial boosters. [“Reverent and Clean,” Ensign, May 1986, 51]

I compare that with the mindless gutter language that washes over us as we watch television, movies, or walk down the street. I loved the movie Apollo 13 but was interested, and relieved, when I read an interview of one of the astronauts from that amazing flight. Commenting on the film, he said it was pretty accurate except that no one on the crew swore, there was no antagonism between crew members, and they did not drink alcohol while in training. Apparently the makers of the movie felt the need to use profanity to pump some energy into dialog that lacked, in their minds, vigor or interest—sort of like adding too much salt to watery soup to cover the absence of more nutritious ingredients. Surely this story had enough body that it did not require those extra few handfuls of salt.

The law has a term, fighting words, for insults so foul that the victim of such insults is entitled to fight back. In the words of one court, “[Fighting words] by their very utterance provoke a swift physical retaliation and incite an immediate breach of the peace” (Skelton v. City of Birmingham, 342 So. 2d 933, 936-37 [Ala. Crim. App.], remanded on other grounds, 342 So.2d 937 [Ala. 1976]). The words themselves constitute assaults. If you are interested in what words those might be, listen to some of the more popular rap recordings. I have been dismayed to read in legal literature that some scholars think these words have become so common in general public discourse that, except for one or two racial epithets, there may no longer be words that meet the legal standard of fighting words. I disagree and would like to share two experiences I had this year.

My son is a basketball player. In the last seven years I have seen perhaps 120 high school or Junior Jazz basketball games. I have also heard perhaps every fighting word in the book on the lips of players, coaches, or referees. It has become an accepted strategy for some players to subject their opponents to a stream of foul language to upset them, put them off their game, or (best of all, it seems) to goad them into fouling. In one game, one of my son’s teammates was subjected to a continuing verbal assault from a referee, who told the boy he intended to make him behave so badly that the ref could throw him out of the game.

An even sadder instance involved a different ballplayer at a different game. A boy about 10 years old was sitting on the floor underneath the home team’s basket, yelling every obscenity and profanity the mind could recall at one of our boys who was waiting to rebound. Here was a 16-year-old basketball player trying to stay calm and focused being riveted by a barrage of filth, his teammates yelling his name repeatedly to refocus him on the game. Parents, teachers, principals, coaches, and referees took it for granted. What does it say when we consider foul language to be an acceptable strategy in school sports competitions?

I love the grace, strength, and skill of basketball. But sitting in the stands I sometimes find my heart racing and my blood pressure shooting up as if I were being mugged when I am surrounded by booing, shouting, disrespect, and harassment of players and referees. If we really love the game, as opposed to a gladiatorial contest, we don’t want garbage. In too many sports events, and in television shows like The Weakest Link and American Idol, the real sport is the abuse.

The referee should have known better. The parents, teachers, and players should have known better. They were not witless or helpless. They made choices about the language they used and tolerated. Those choices tell us much about them—and ourselves when in the same position.

Elder Charles Didier taught us to remember:

Words are a form of personal expression. They differentiate us as well as fingerprints do. They reflect what kind of person we are, and tell of our background, and depict our way of life. They describe our thinking as well as our inner feelings. [“Language: A Divine Way of Communicating,” Ensign, November 1979, 25]

Elder Didier went on to say:

Language is of divine origin. Only man speaks (and women do even better), and he does so because of the purpose for which he was created. Let us listen to Paul when he said: “Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal” (1 Cor. 13:1). Anacharsis, when asked what was the best part of man, answered: “The tongue.” When asked what was the worst, the answer was the same: “The tongue.”

“Therewith bless we God, even the Father; and therewith curse we men, which are made after the similitude of God.

“Out of the same mouth proceedeth blessing and cursing. My brethren, these things ought not so to be.

“Doth a fountain send forth at the same place sweet water and bitter?

“Can the fig tree, my brethren, bear olive berries? either a vine, figs? so can no fountain both yield salt water and fresh” (James 3:9–12). [Didier, “Language,” 25]

Words can be healing balm or gasoline on a fire in disputes with neighbors, friends, or colleagues. Television and movies create a tolerance for overblown emotion. Where once we sought the subtle or understated, now we often feel the need to heat up our vocabulary. Consider these different ways to make the same point:

1. “I don’t remember things that way” or “You are lying.” Or, my personal favorite, “You are a fraudulent malfeasor!”

2. “Let’s think together to try to solve this problem” or “That’s dumb. Let me do it. I know the right way.”

3. Or, turning back to my basketball stories, consider the parent of one of my son’s teammates, who proposed that our parent rooting core quit yelling negative comments to referees who were doing a poor job but praise them when they did well and encourage our boys on in the face of adversity. It seems to be making an impact in the tenor of games and has even perhaps reduced, though it has not stopped, the foul language.

When we attack people with whom we disagree, we injure or even end our ability to resolve disputes. Each time we raise the temperature in the discourse it is harder to reconcile differences. We raise a barrier of hate and anger. Elder Richard L. Evans counseled: “We are in a sense as much responsible for what we do to others with our words as we could be with weapons. In a sense, you can hit a man with words—’words as hard as cannon balls’ as [Ralph Waldo] Emerson said it [Self-Reliance]” (“The Spoken Word: ‘Words as Hard as Cannon Balls,’” New Era, December 1971, 34).

Words can be powerful in a positive way. Think of Alma’s experience with the Zoramites:

And now, as the preaching of the word had a great tendency to lead the people to do that which was just—yea, it had had more powerful effect upon the minds of the people than the sword, or anything else, which had happened unto them—therefore Alma thought it was expedient that they should try the virtue of the word of God. [Alma 31:5]

The Apostle Paul admonished us: “But now ye also put off all these; anger, wrath, malice, blasphemy, filthy communication out of your mouth” (Colossians 3:8).

Tenderness and loving speech are more important in families than anywhere else. My mother and I were at a dinner with a large family that was, for the most part, loving. There was one particularly attractive young couple. Their three beautiful children were talented and bright. The parents were successful in the community and apparently had everything. Later we were talking, and Mother grieved over the couple because of the pain in their relationship. I questioned her judgment. They were joking, laughing—the life of the party. She was not fooled by the jokes. Each one had an edge, she said. Every funny comment by one put the other in a bad light. Two years later they were divorced. Mother saw, as I did not, that cutting, hurtful words are not ameliorated by humor—just disguised to the inattentive.

Loyalty in a family means that we are loving in word. Again, Elder Didier gives great guidance:

Language is divine. Some may know this but do not realize its implications in their daily family life. Love at home starts with a loving language. This need is so important that, without loving words, some become mentally unbalanced, others emotionally disturbed, and some may even die. No society can survive after its family life has deteriorated, and this deterioration has always started with one word. [Didier, “Language,” 26]

And it is always a hurtful word.

Studies of couples who stay married for 30 or more years show that they are kind to each other. Their criticisms, when they come, are couched as exceptions in a nest of praise and love. I did a Google search on the term lasting marriage. The results? There were over a quarter of a million entries. I did not tally all the suggestions. I did page through the first 50 or so. The overriding theme was to be loving, resolve conflict, and be respectful of each other.

Elder Lynn G. Robbins wrote of Satan’s efforts to destroy families:

He damages and often destroys families within the walls of their own homes. His strategy is to stir up anger between family members. Satan is the “father of contention, and he stirreth up the hearts of men to contend with anger, one with another” (3 Ne. 11:29; emphasis added). The verb stir sounds like a recipe for disaster: Put tempers on medium heat, stir in a few choice words, and bring to a boil; continue stirring until thick; cool off; let feelings chill for several days; serve cold; lots of leftovers. [“Agency and Anger,” Ensign, May 1998, 80; emphasis in original]

Finally, as a mother, grandmother, great-grandmother, and Primary president, I must talk a bit about words that heal children and words that wound them. Children are tender. They want to please. They want to do right. Sometimes they do not know how to do so, but they will strive to do right unless they are beaten down. We have all lost our temper on occasion with a particularly persistent child. But remember the Savior’s love for them. His admonition, repeatedly, is that we should seek to be like them.

But whoso shall offend one of these little ones which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea. [Matthew 18:6]

A child may, and will, make mistakes. She may do bad things, but she is not bad. Psychological studies suggest that a child’s brain is forming and reforming, building connections and synapses. When we discipline or reprimand a child, we are truly building that child. If we teach a child she is bad, we teach her to be bad. If we teach a child she is good, she strives to become good.

My son Philip persisted in asking me, when he was a child, if he was perfect. I had a rare moment of insight and knew that either a yes or no answer had pitfalls. If he was perfect, there was no room for growth. But he was clearly telling me he wanted and needed approval. I hit upon a compromise: “You are a perfect five-year-old.” This was not exactly what he wanted to hear. What was a perfect five-year-old? It gave us a chance to talk about all the things he did well, how he was loved by his heavenly and earthly parents, and how he could grow to be a wonderful adult and return to his heavenly parents—not just a perfect five-year-old but one day perfected. Although he wanted another answer, he found mine acceptable. Through the years he has asked me if he is perfect. At about the age of 12 he came to accept my answer. “You are a perfect 12-year-old.” Over time he has developed an understanding of the doctrine of eternal progression. He still desires to be better. He knows he has ample room to grow and improve, though sometimes his lack of perfection frustrates him as it did when he was five. But he accepts the process.

President David O. McKay counseled:

Three influences in home life awaken reverence in children and contribute to its development in their souls. These are: first, firm but Gentle Guidance; second, Courtesy shown by parents to each other, and to children; and third, Prayer in which children participate. [CR, October 1956, 6–7; emphasis in original]

All of these three influences involve words.

Everything given to us by our Father is given for our eternal salvation. However, any gift can be abused or turned to evil purposes. Words, the power of language, are among the greatest gifts. I pray we can use words for our edification and bless the lives of others, and I do so in the sacred name of Jesus Christ, amen.

© Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

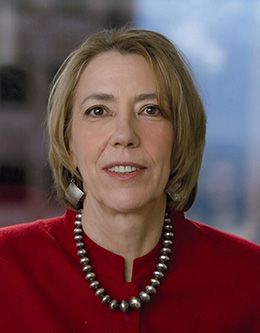

Constance K. Lundberg was associate dean and library director at the BYU J. Reuben Clark Law School when this devotional address was given on 11 March 2003.